Two years into the Lebanese people’s collective campaign for accountability from their leaders, a deadly Beirut street battle was a not-subtle reminder of how entrenched powers resist change.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Trudy Palmer

Trudy Palmer

It likely comes as no surprise that people in the United States believe there’s considerable conflict between those with different backgrounds or political viewpoints. We’re not alone in that. Pew Research Center’s survey of 16 other advanced economies found the same, though typically to a lesser degree.

The U.S. and South Korea tied for the top spot regarding political conflict, though, with 90% of those surveyed saying there are very strong or strong conflicts between those who support different political parties. Taiwan came in next at 69%, with France and Italy close behind.

The U.S. also topped another category, with 71% finding very strong or strong conflicts between people with different racial or ethnic backgrounds. France was next at 64%.

Maybe you’re thinking, “Tell me something I don’t know.”

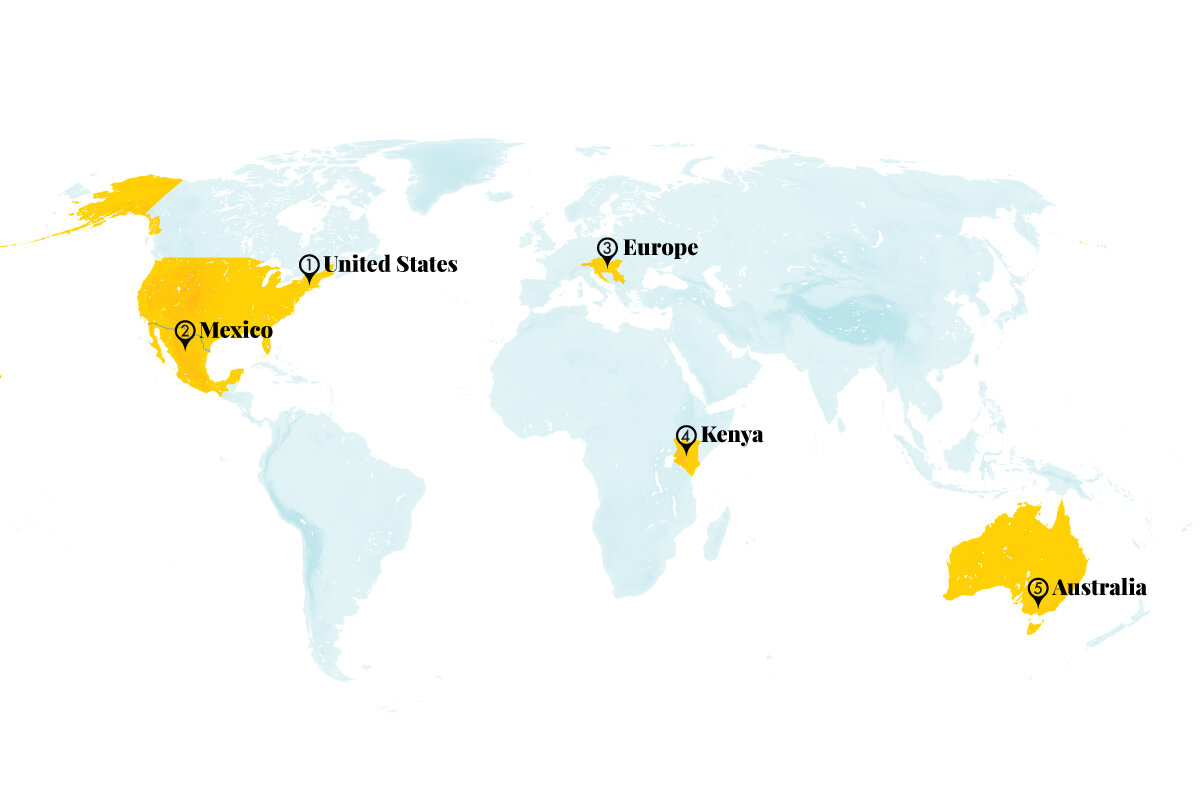

Well, Pew’s survey did that, for me at least. And I admit, it was a relief. In all but two of the 17 nations, roughly 60% of those surveyed said that diversity improves society. Better still, “in many places – including Singapore, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and Taiwan – at least eight-in-ten describe where they live as benefiting from people of different ethnic groups, religions and races,” Pew says. Even the two outliers – Greece and Japan – reported double-digit increases since 2017 in those who regard diversity favorably.

My takeaway? Despite not getting along very well right now, most people recognize that differences enrich us. In other words, as lovely as a well-manicured lawn may be, there’s a lot to be said for a field of wildflowers.