Since the late 1980s nearly every Latin American country has sought in some measure to become more democratic. Several have adopted entirely new constitutions. Others have introduced significant constitutional reforms. These changes reflect a deepening embrace of common principles: religious and cultural diversity, gender equality, respect for property rights, and recognition of civic rights for all. Progress has been halting and uneven, but as two former White House officials, Richard Feinberg and Benjamin Gedan, wrote last month in World Politics Review, “the region’s democracies have proved surprisingly robust time and time again.”

Now Chile is poised to bend the arc of democracy in Latin America further. Over the last two days, it held elections for a new assembly tasked with replacing a constitution drafted under former military dictator Gen. Augusto Pinochet. That 1980 constitution provided a foundation for Chile’s return to democracy in 1990. In the three decades since, Chile has become one of the wealthiest, stablest, and least corrupt countries in the region.

That growth, however, also resulted in accelerating economic inequality. According to the latest survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 53% of Chilean households are financially vulnerable: The poorest 20% earn just 5% of total national income. Popular discontent has erupted repeatedly during the past decade, first in student protests over university tuition and then, in 2019, a modest hike in public transportation fares in Santiago, the capital. The latter sparked what came to be called “the awakening.” Yielding to mass demonstrations nationwide, the government called for a referendum last October on whether to draft a new constitution. It garnered the support of 78% of Chileans.

The plebiscite’s second question was even more significant. Voters were asked to decide who would draft a new constitution – elected officials or a new constitutional assembly chosen by the people. Seventy-nine percent opted for the latter. That set the stage for the ballot held over the weekend.

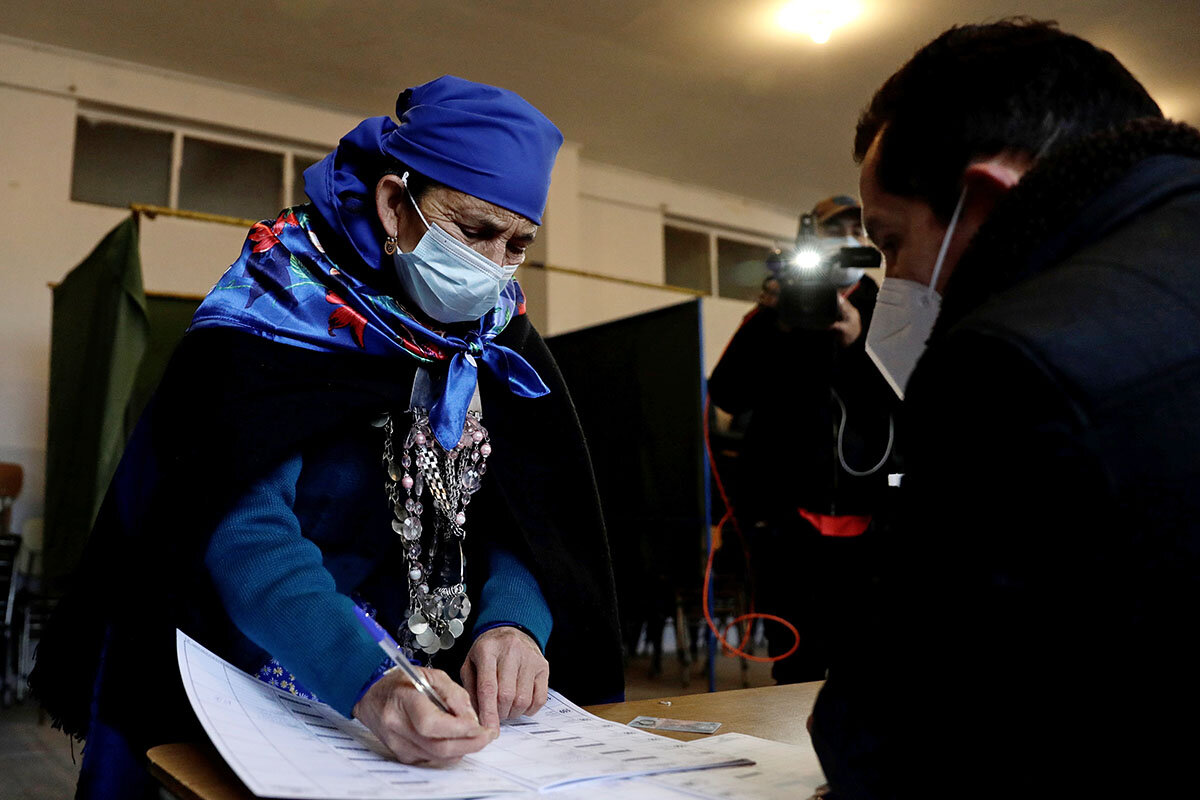

The design of the new constitutional assembly reflects shifts already taking place in Latin America toward greater recognition of the rights of women and minorities. Unlike other countries that have adopted quotas – it took 15 years, for instance, for Mexico to achieve its gender parity goals in the national parliament – Chile built in guarantees. Of the 155 seats in the constitutional assembly, half must be filled by women, 17 for Indigenous candidates, and seven for people with disabilities.

That distribution reflects a key lesson taken from constitutional reforms worldwide: A 2019 study by scholars at American University in Washington and Loyola University in Chicago of 195 new constitutions over the past 40 years found that “inclusion is what matters.”

The assembly has until August 2022 to draft a constitution that strikes a new balance of power between the executive and legislative branches, and between individual empowerment and the common good. Expectations are high. As Maribel Mora Curriao, a Mapuche poet, told Al Jazeera outside a polling station in Santiago, “We are voting with pride and identity for the first time. We take this process very seriously and we are very much aware that this is a unique opportunity not only for us but for the Chilean people as a whole.”

A campaign slogan from the community of disabled Chileans put it more succinctly: “Nothing about us without us.” As a region watches, the people of Chile have set a new course toward an ageless idea: government of the people, by the people, and for the people. It is a project compelled neither by the result of war nor an attempt to perpetuate political advantage, but by an insistence that power derives legitimacy through each individual’s expectation of the common good.

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp