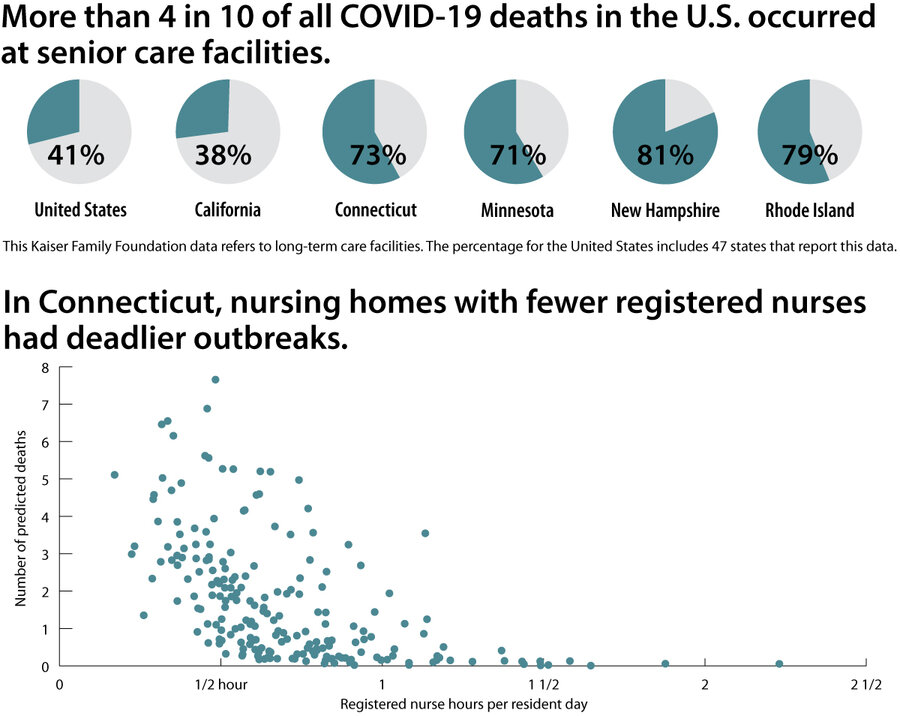

The pandemic has raised questions about how our investments as a society reflect our values. That’s come up in the context of U.S. nursing homes, where there’s often a dearth of senior nursing expertise.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Even in the context of El Salvador’s brutal civil war, the 1989 massacre of five Spanish Jesuits was shocking, spurring global calls for justice. On Friday, 31 years later, those calls were answered as Spain’s top criminal court handed a life sentence to Inocente Orlando Montano, a former Salvadoran army colonel and security minister, for his role in the murders.

The case was argued in Madrid because of universal jurisdiction, which allows one country to investigate human rights crimes in another. And it speaks to the value the world continues to assign to the promise of international justice.

Staff writer Howard LaFranchi has written frequently about international justice, most recently regarding the arrest of a fugitive complicit in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Cases can be a long slog, he says, and in addition to global institutions, individuals play important roles. He recalls visiting Argentina years after the Dirty War of the 1970s, and going to the home of a father whose daughter was disappeared. “What struck me was how people stuck with it,” he says. “He relentlessly pursued the case. So did mothers who for years gathered every Thursday in Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo demanding answers.”

In Mr. Montano’s case, prosecutor Almudena Berabéu echoed that, lauding the persistence of Salvadorans. She told The Guardian, “It doesn’t really matter if 30 years have passed. I think people forget how important these active efforts are to formalise” that someone was tortured or executed.

As Howard says, “The principle of justice remains in people’s beating hearts.”