The coronavirus may not significantly alter the course of history, but it will likely change how we live our lives and what we value as a society.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

David Clark Scott

David Clark Scott

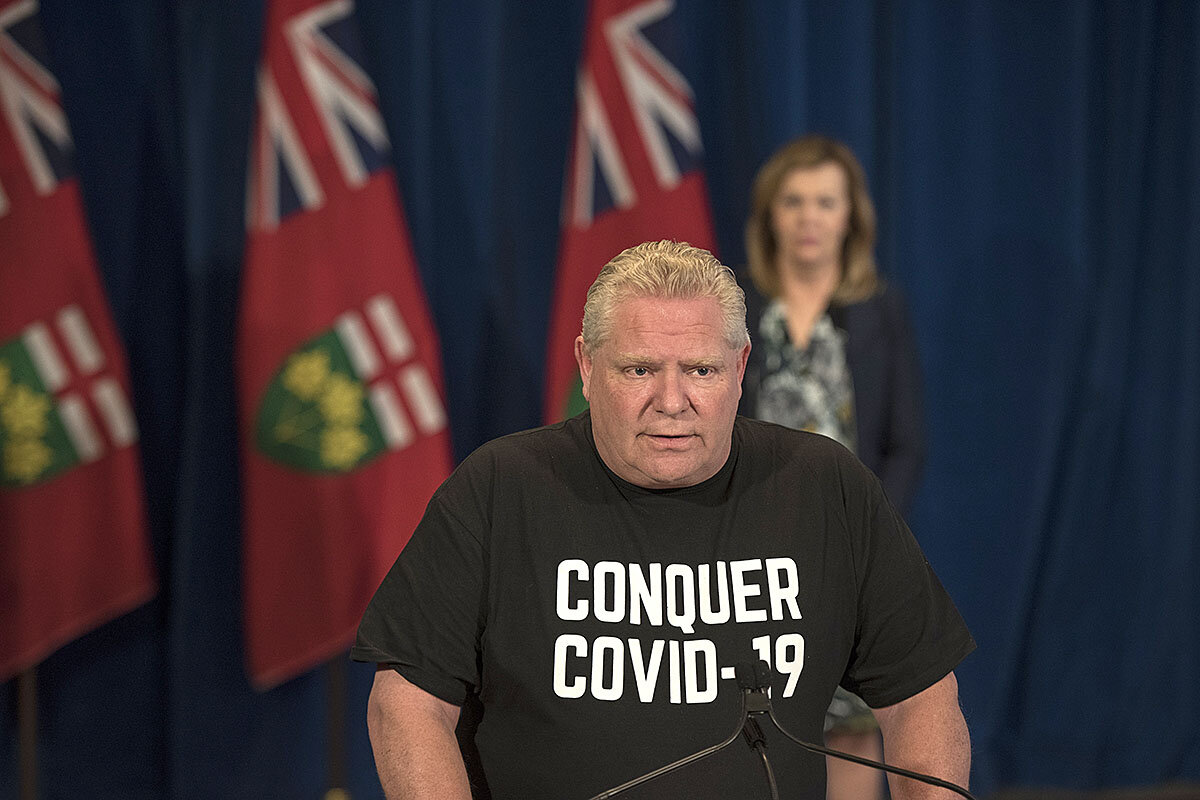

Today’s five selected stories cover shifting U.S. values in a pandemic, a Canadian profile in leadership, history lessons about navigating financial hardship, challenging misinformation with an African song, and what nature teaches us about resilience.

I have a soft spot for the drive-in movie. My first glimpse of that big screen magic came on a tropical summer night as a 4-year-old in pj’s peering out the back of our Ford station wagon. My first date with the girl in high school who became my wife was to a drive-in movie. My daughters and their friends grew up loving the premovie picnic and pickup soccer before settling in for a double feature.

Now this almost forgotten American pastime is seeing a renaissance. People are desperate to get out. In some states, it may violate the spirit of shelter-in-place, but one Florida drive-in owner argues that your car is really an extension of your living room. Many open-air theaters have closed their concession stands to uphold social distancing rules.

In Queen Creek, Arizona, Schnepf Farms just put a movie screen on a tractor-trailer in a field to help replace its lost wedding and festival business. At $15 per carload, the new 60-car drive-in has sold out every night since opening two weeks ago. The popularity “caught us by surprise,” Mark Schnepf told KPHO-TV in Phoenix.

It shouldn’t have, really. For me, the drive-in represents family bonding. A silver lining to this tragic pandemic is that a new generation is being introduced to a unique community event, and getting to experience the childlike anticipation that builds as the sun slowly sets and the air fills with a chorus of crickets and the perfume of popcorn.