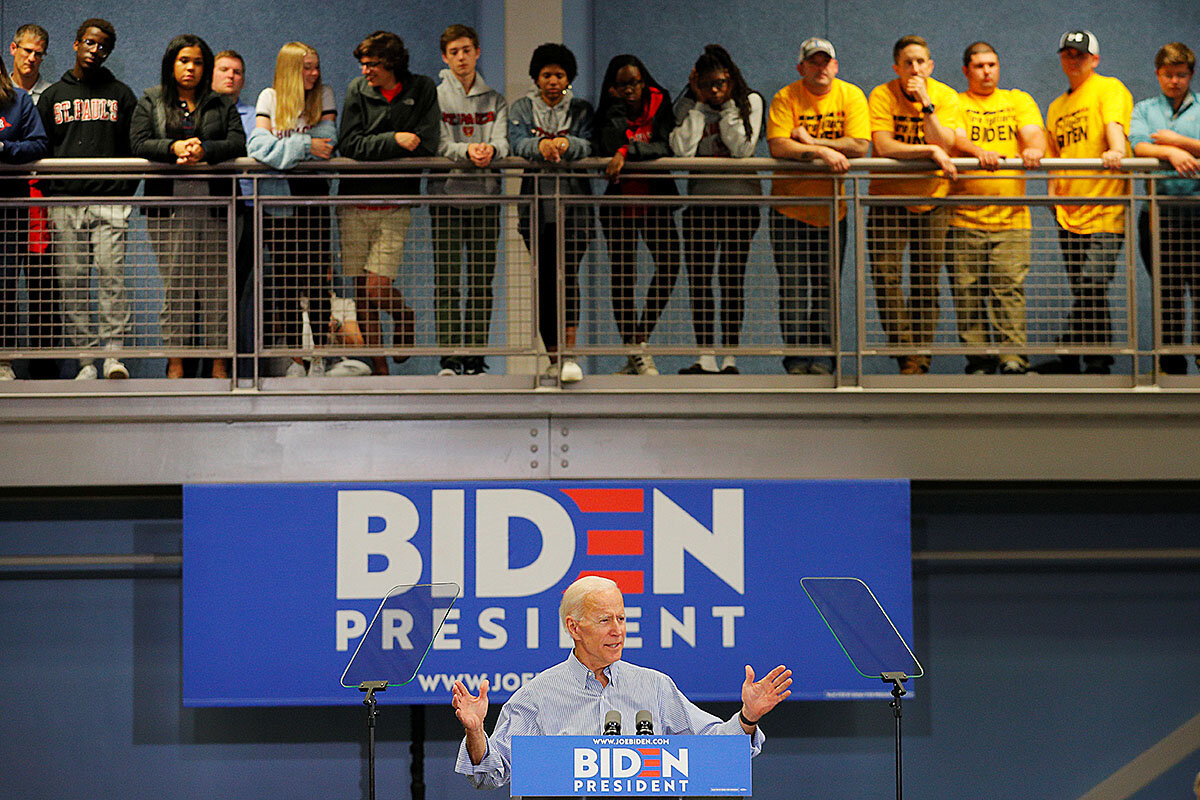

While young progressives get most of the headlines (from both the right and the left), more Democratic voters resemble Joe Biden: older centrists. In New Hampshire, voters say his calls for unity resonate in a deeply divided country.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

The plan seemed like something out of “Oliver Twist,” circa 2019. Students in Rhode Island’s Warwick School District who could not pay for lunch would instead be given cold “sun butter and jelly” sandwiches (whatever those are). There is no word on whether those wanting seconds would be greeted by hair-netted servers yelling “More?”

Nobody likes solutions like these. At its worst, it becomes “lunch-shaming” – turning kids who can’t afford food into objects of derision. Elsewhere, students who can’t pay for lunch have had to wear wristbands or get hand stamps.

An article in The New Food Economy, however, shows the other side. Lunch debt is becoming a major concern as cash-strapped public schools struggle to meet budgets. What should they do?

In Warwick, the $77,000 deficit has prompted tens of thousands of dollars in donations from parents and philanthropists – including nearly $50,000 from yogurt-maker Chobani, NPR reports. “No child should be facing anything like this,” said CEO Hamdi Ulukaya in a tweet.

At the moment, donations seem to be the only answer. The broader question is about what we expect a public education to provide. In many districts, teachers are paying for snacks and supplies out of their own salaries. How does food fit into that calculus? Says one expert to The New Food Economy: “School meals are just as important to student success as textbooks and teachers in the classroom.”

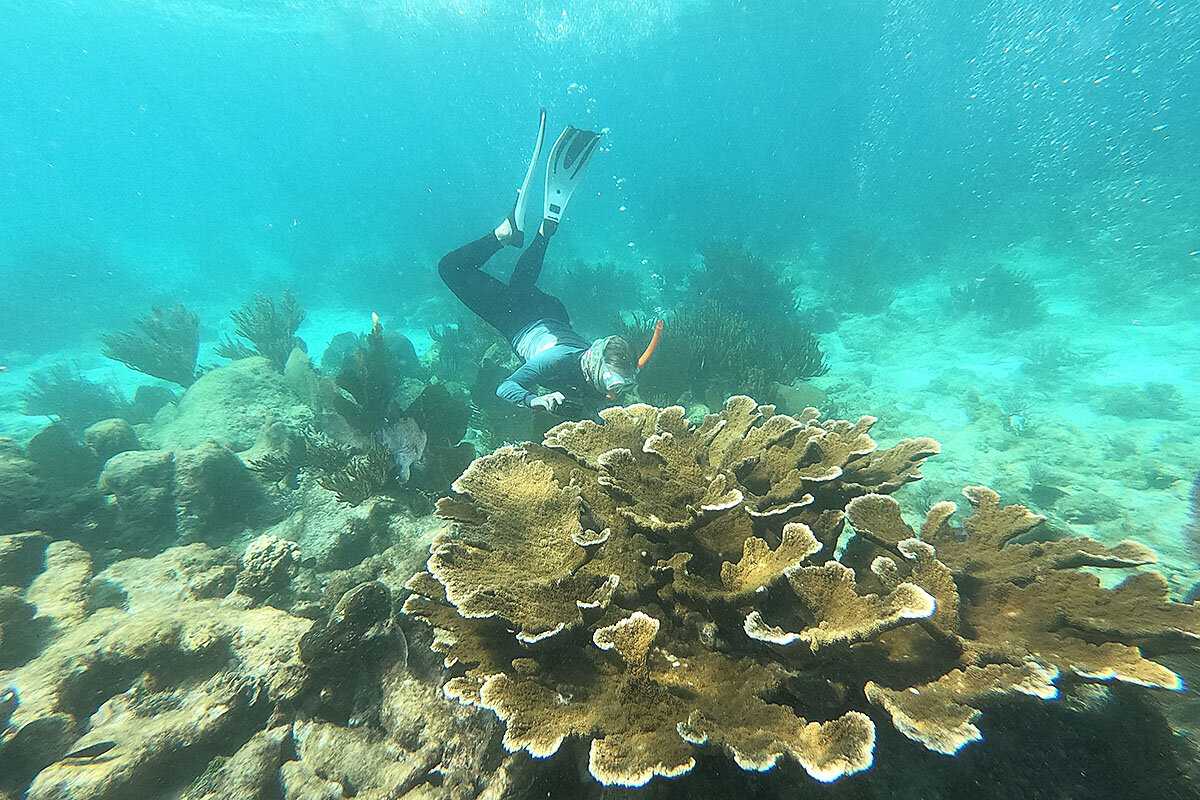

Now on to our five stories. They include a look at China’s emerging vision for Hong Kong, a Belize reef that could help save other reefs, and a different kind of memoir on race in America.