It's a question that ever more urgently needs addressing: What are the implications for a democracy in which many voters don't trust media reports about their president – and how can all players address that?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

How do you address justice in the case of drug offenders?

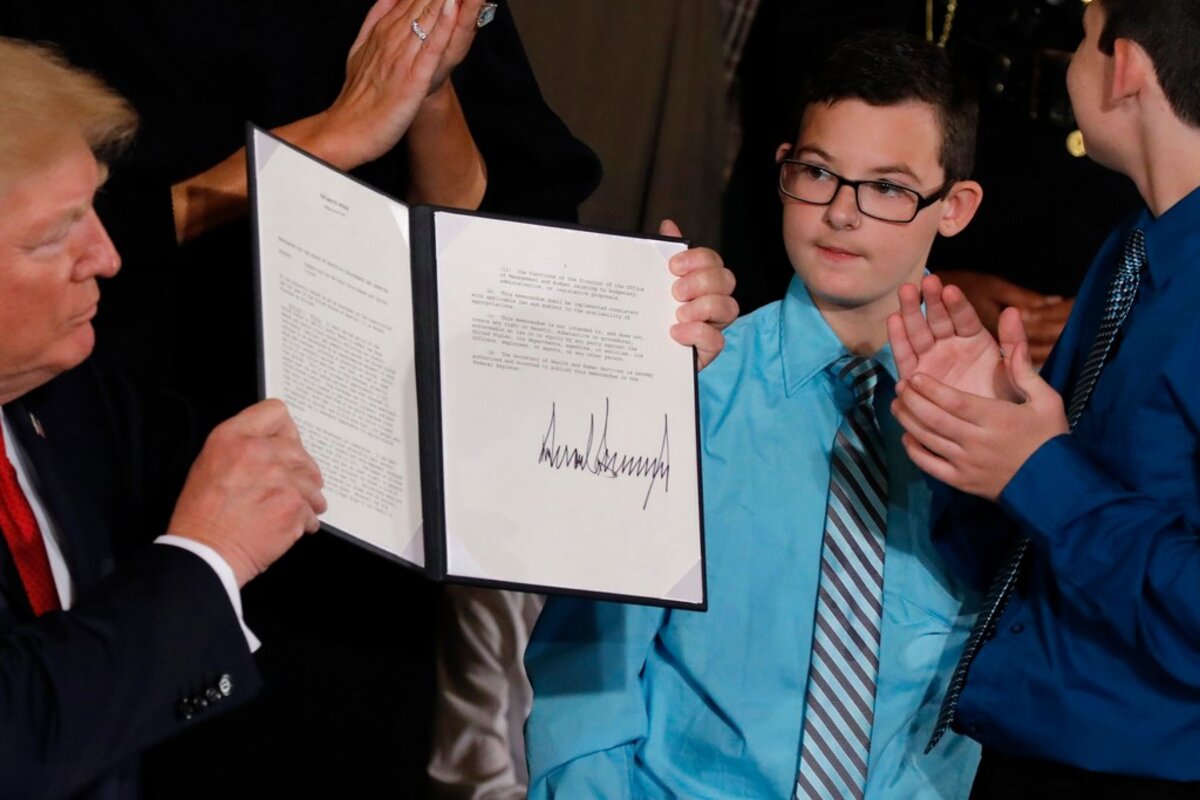

Today, President Trump declared the US opioid crisis a public health emergency. For 90 days (or longer, if it’s extended), federal agencies can use emergency authorities to address a scourge that killed 64,000 last year. States will also have flexibility in deploying federal funds.

Among those struggling to address the crisis are law enforcement officials. And as they look for new approaches, they might take inspiration from Buffalo, N.Y.

That’s where Judge Craig Hannah presides over a pioneering opioid intervention court. It eschews jail time in favor of fast-track treatment. If defendants want help, criminal charges are put on hold, and treatment begins immediately. Frequent contact, especially as someone moves to out-patient status, means the court can address problems quickly – including with an arrest warrant if necessary. Once a defendant is in recovery, the case is reactivated – with the prospect of reduced or dismissed charges.

Judge Hannah gets to know the people who come before him. That may explain why he’s seen only a handful of failures among some 140 defendants. As one told NPR: “Judge Hannah has been the most helpful, useful person I've had in my life in the last eight years. If I wasn't [in this court] I think I'd be dead.”