"Trump: The Art of the Deal" was the story of Donald Trump throughout the 1980s and '90s. But the president has struggled to carry it into the Washington context.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Why argue with a rise in good grades?

We learned this week that nearly half of US high-schoolers are graduating with not just an A here or there, but A averages. A new study finds that in 1998, some 38.9 percent of graduates hit that mark. In 2016, the figure rose to 47 percent.

But over the same period, SAT scores slipped. While not a perfect counterpoint, it suggests that something more than improved study habits is going on.

We’ve long known about grade inflation and its suggested culprits: the self-esteem movement, helicopter parents, entitled kids, lenient teachers, college pressures, even the Vietnam War (think draft deferments).

What may be less apparent are the costs. You’ll find a lot more of those A's in communities that are affluent and whiter, according to the study. Since GPAs still matter, that means low-income students and students of color may be at a disadvantage – widening the inequality divide.

But there’s another issue: When the brass ring becomes a quotidian credential, it diminishes genuine achievement and the requisite hard work. And as Gilbert and Sullivan put it in “The Gondoliers”: “When everyone is somebody, then no one’s anybody!”

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Overlooked

( 5 min. read )

While everyone has been focused on Russian hacking, a lesser-noticed digital battle has been under way in the Middle East.

( 4 min. read )

A summer job in, say, a pizza joint doesn't strike a lot of high-schoolers as a path to a brighter future. But the lessons such work can teach are being rediscovered – even as the kids who need it the most struggle to find options.

( 5 min. read )

As we noted above, teens often struggle to see a path forward. But if they can get more help, the outcomes might be different – a hypothesis Chicago is about to test.

On Film

( 3 min. read )

Americans have an almost insatiable appetite for accounts of World War II, perhaps because the conflict seemed like such a clear battle between good and evil. Our film critic, Peter Rainier, has a mixed review on the latest epic take on an epic battle in 1940.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

The closer that economists look at the rise in income inequality, the more they find one cause may be the rise of another inequality: The least productive firms are falling further behind the most productive firms. The Kmarts of the business world aren’t keeping up with the Googles. And one reason is a widening gap in innovation, creativity, and, more fundamentally, a curiosity to discover and embrace new ideas.

This point was made in a recent study spanning 16 countries by the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. It found the “productivity gap” between firms in the top 10 percent by productivity and those in the bottom 10 percent rose by about 14 percent from 2001 to 2012.

“The corporate landscape has become increasingly unequal,” the three authors of the study write in a Harvard Business Review article. “This matters not just for economic growth but also for [pay] inequality.”

Most companies try to increase the quality and quantity of their workers’ output, or what is called the productivity rate. As Janet Yellen, chair of the Federal Reserve, often tells Congress and others, productivity growth “is what really determines in the long run the pace of [economic] growth.”

But individual companies can fall behind competitors if they lag in their flexibility to change and their openness to new technologies or fresh ideas in workplace management. The traits of highly productive firms require that staff have boundless motivation to learn and adapt. In short, people must keep asking questions.

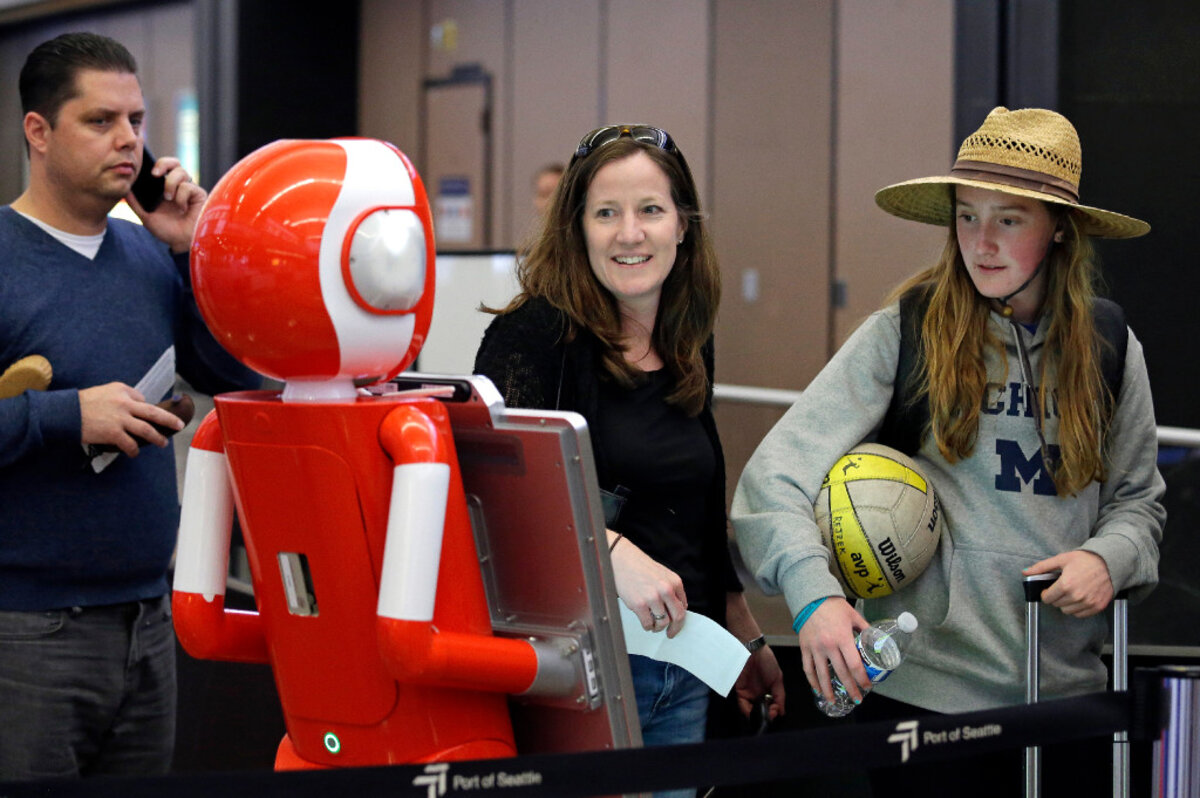

By their very desire to understand and cope with the world, humans ask questions. Computers, on the other hand, must be guided to do so and are given goals or limits. Companies certainly must tap artificial intelligence (AI) or machine-learning robots to raise productivity. Automation helps overcome human bias or limits. AI can perceive opportunities in “big data.” But it cannot replace human inquisitiveness, or the impulse to ask “why.”

Companies and workers looking to raise their productivity – by boosting curiosity – may be helped by a new book, “Why?: What Makes Us Curious,” by famed astrophysicist Mario Livio. He worked on the Hubble Space Telescope and the window it opened to the cosmos. This led him to become curious about curiosity, starting with humanity’s early spiritual quest for meaning.

His book explores the limited research on curiosity and dives into the lives of inventive people, such as Leonardo da Vinci. Dr. Livio found curiosity can be divided into two types: one that seeks to solve problems and the other that loves understanding just for the joy of it. In the first, curiosity is a cure for fear. The second opens even more questions and leads to new discoveries.

Sometimes the two combine. “Love of knowledge does create a reward for its own sake, but you want to feel results,” he writes. “

Curiosity is self-sustaining because it keeps unfolding ever-more truths. "Curiosity’s powers extend above and beyond its perceived potential contributions to usefulness or benefits. It has shown itself to be an unstoppable drive,” the book states.

Yet not all curiosity is welcomed. Parents must guard what children learn. We speak of morbid curiosity, such as gawking at a car accident. Or “curiosity killed the cat,” as in getting too close to danger. Under a dictatorship, leaders try to suppress the flow of ideas or demand conformity. In such countries, creativity and productivity can falter.

The constant desire to ask “why” is what distinguishes humans from animals and robots. Curiosity and the intelligence it brings is also essential for innovation in business. And now, because of the inquiring minds of academics, we know it can also be one of the many ways to help reduce economic inequality.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 2 min. read )

One day when contributor Andrea McCormick was alone in her store, some young men came in behaving in the way that fitted a police profile of how a series of recent robberies had been carried out. In that moment, she decided not to focus on the frightening circumstances. Instead, she held to the idea that each of us is God’s loved creation. This calmed her fear. She realized that a desire to do wrong was not inherent in anyone’s nature as the child of God, divine Love. It came to her to talk in a friendly way with the men about a certain collection of items in the store. They listened, engrossed in the story, and then left peacefully without taking anything. It’s natural for everyone to do right, not wrong. We are all safe in God’s love.

A message of love

A look ahead

That's a wrap for today. Join us again tomorrow, when we'll look at new threats to the progress that’s being made by the global community in meeting humanitarian needs.

And a reading suggestion: We hope you'll take a look at this story from two years ago about why police in many countries don't pull their guns. It's particularly relevant after Justine Damond was fatally shot by a police officer last weekend in Minneapolis.