The latest iteration of the Republican health-care plan prompted Monitor writer Francine Kiefer to take a closer look at Medicaid, the US government program intended to care for the most vulnerable Americans.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

We’ll wear skirts!

Essentially, that was the rallying cry of boys at a British high school. No, they’re not Scottish students. But it was really hot this week in Exeter, England. And the boys at Isca Academy were faced with a dress code that forbid them from wearing shorts. Only long, gray pants are allowed.

So, they wore skirts because those are allowed under the girl’s dress code, reports The Guardian.

Yes, Monitor editors know there are more important events happening in the world today (keep scrolling). But this story brings a smile, and the sort of inspired thinking that’s, well, noteworthy.

When faced with rules that won’t bend, even on a sweltering summer day, these boys got creative. They found a cheeky solution to their (sweat-soaked) sartorial statutes.

Isn’t that one of the purposes of education: to learn how to think creatively?

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

( 6 min. read )

To shore up his power, Venezuela’s president is giving the military more control over running the nation’s economy. But that could backfire if the generals decide that the path back to stability is to get rid of the president.

( 4 min. read )

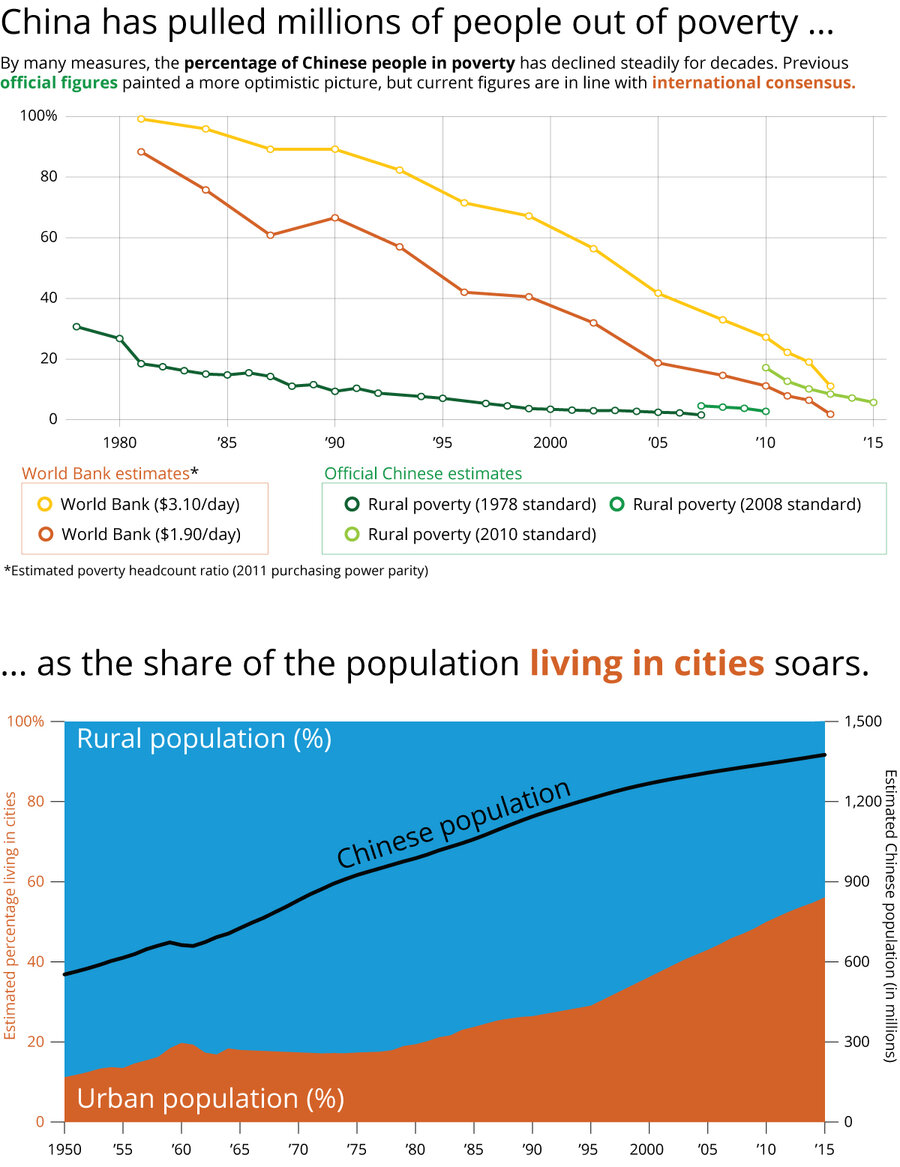

China touts its concerted efforts to end poverty. It appears to be making huge strides. But we wondered: How credible is this path to ending economic inequality?

( 5 min. read )

Increasingly, Millennials are rising to positions where they can change how US companies work. This next story looks at the values shaping their choices – and their workplaces.

( 5 min. read )

Our next story is about how one woman’s perseverance can make a difference in the quality of life of an entire village.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

In at least five countries, American military personnel are on the ground battling terrorists. In March, the Trump administration threatened a preemptive strike on North Korean nuclear facilities. In April, it launched missiles against Syria for its use of chemical weapons. And in recent days, the United States has shot down Iranian drones and a Syrian fighter jet, creating a potential flashpoint with Russian forces.

Like many presidents before him, Mr. Trump has initiated military actions as commander in chief without clear approval from lawmakers. The last time Congress fulfilled its constitutional duty by actually declaring war was in 1941. But now many on Capitol Hill say recent US military actions, including those during the Obama era, should compel Congress to provide a new type of approval.

The last time Congress granted some broad powers to the president for military action was in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Lawmakers – most of whom are gone – passed two resolutions called Authorization for the Use of Military Force. Since then, however, terrorist groups have evolved. To many scholars, AUMF is out of date. And the US, even as it fights Islamic State in many places, is struggling in Syria to define which of the many warring parties is a foe.

Nonetheless, the real reasons for a new authorization are moral ones.

Soldiers who put themselves at risk must know that Americans, through a bipartisan consensus of lawmakers, support a strategic goal. In addition, an open deliberation in Congress over authorization might improve a military strategy or drive the US to seek peaceful means. And to prevail in a conflict, the US must make clear to its adversaries that it has long-term national resolve.

By acting lawfully in its military operations, the US can also influence other countries to do the same. Such behavior then encourages more countries to follow international norms and laws in the use of force across borders.

For the first time in years, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee held a hearing June 20 on a new AUMF. The panel considered a bill, proposed by Sens. Tim Kaine of Virginia, a Democrat, and Jeff Flake of Arizona, a Republican. The measure attempts to bridge differences between the parties over how much operational authority should be given to a president. It sets limits, for example, by defining specific terrorist groups in six countries. And the AUMF would be valid for only five years.

In his last year in office, President Barack Obama proposed his own AUMF. But in an election year, it didn’t go anywhere. Now Congress should seriously consider such a bill. What it needs first, however, is a concrete counter-terrorism policy from the White House. That would be a starting point for a national debate.

Waiting 16 years to renew such congressional authority has consequences for the nation’s integrity. As Kathleen Hicks of the Center for Strategic and International Studies told legislators, an out-of-date authorization “jeopardizes our nation’s principled belief in the rule of law and thereby risks the legitimacy of the institutions designed to create, carry out, and enforce such laws.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

When contributor Blythe Evans worked in Gabon, a country far from her New York home, she needed to rely on strangers for transportation. At one point, traveling through a remote area at night, fear for her safety threatened to take over. But then she thought of the 91st Psalm, which begins, “He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty.” Despite the precariousness of her situation, a deep sense of being safe in God’s care took over, lifting her free of fear, and she reached her destination without incident. Even in frightening or uncertain circumstances, we can feel the order and calm of infinite Love.

A message of love

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a video about what history tells us about US presidents and their contentious relationship with the media.