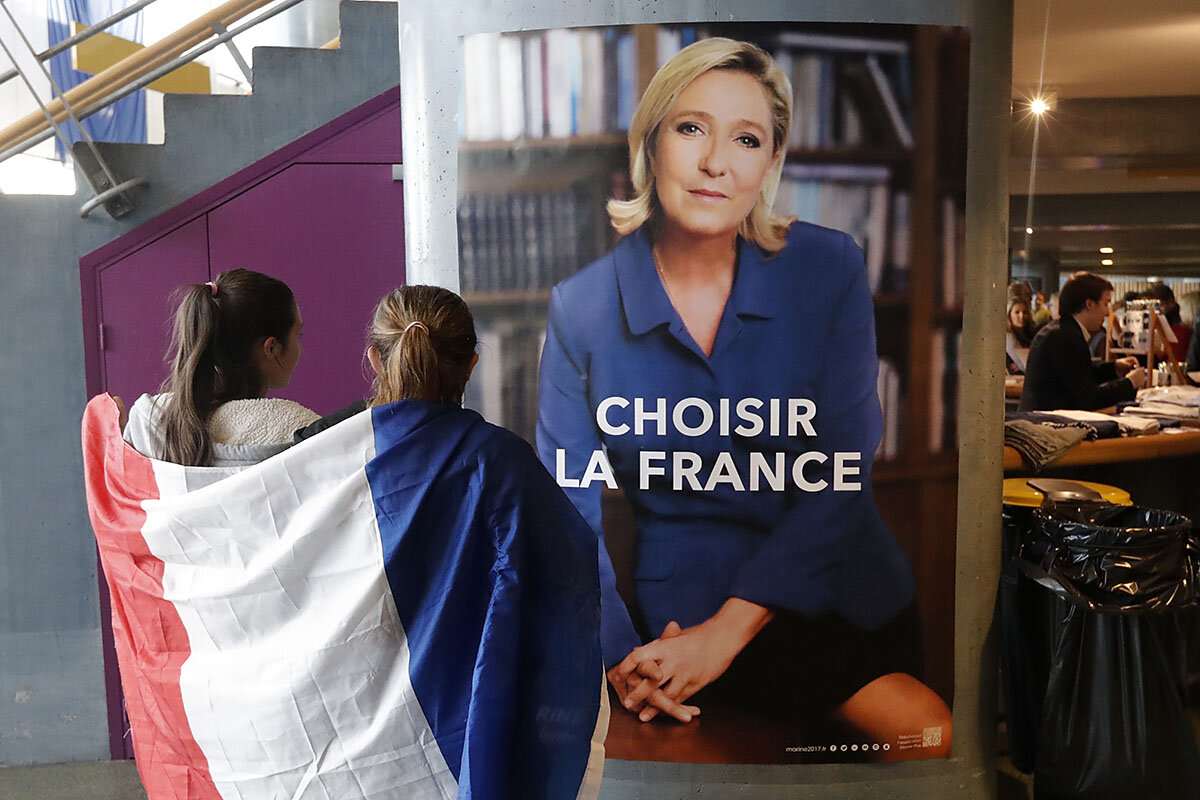

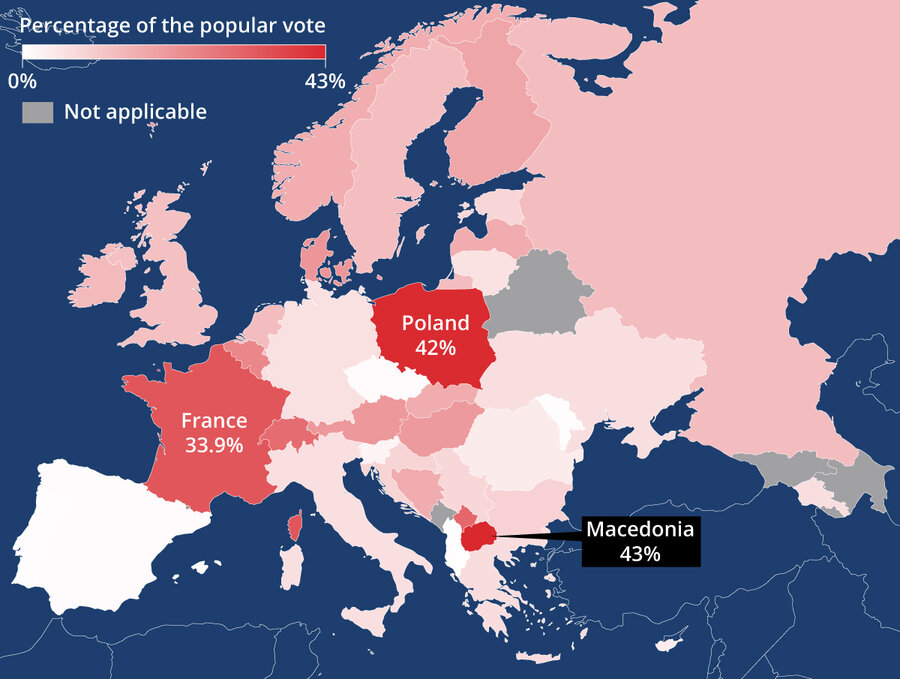

In recent months, we heard so much about Marine Le Pen's radical view of French politics. But in some ways, President-elect Emmanuel Macron's vision is just as radical: He's trying to revolutionize French politics from the inside out.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today, the first day of the new Christian Science Monitor Daily, there is interesting news out of Britain. Facebook announced an effort to crack down on “fake news” ahead of elections next month. It’s banning dubious sites and telling readers to be alert. But what is fake news, really? Research suggests that people can see events completely differently, depending on whether they are in the majority or the minority. In other words, it’s not really just a question of facts, but also of perspective.

Facebook’s efforts are welcome, as are the efforts of fact-based journalism. Both are necessary. But the Monitor has always worked to take facts deeper – into ideas and solutions. And that’s the point of our new Daily: How we see the world matters. The answer to fake news is understanding – not just of facts but of each other and of the values that shape our lives. Today, we start our newest effort to show that light to the world.

Here are our top five stories for the day: