The peaceful dialogue of Latin America

Loading...

With just a little searching on the internet, it is possible to find scores of current examples of people across Latin America striving to overcome persistent violence and economic hardship. Mayan women raising chickens in Guatemala rather than trekking north to seek jobs in the United States. Mothers of gang members in Honduras mediating peace in their urban barrios. A lone priest in Mexico refusing to be interrupted by armed men while delivering his sermon.

Taken individually, these may seem more anecdotal than noteworthy. At a time when gang violence and organized crime are surging across countries from Mexico to Ecuador, however, such humble measures of community are at the center of a regional debate about peace and governance.

Criminal groups are “a symptom that the social contract is in question,” said Mauro Cerbino, a professor at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences in Ecuador. He told Civicus, an alliance of civil society groups, that “any effective response will therefore need to ... rebuild the community – through education, art, dialogue and culture – to confer meaning on the lives of so many young people” who feel unvalued and without purpose.

One response that has gained currency among regional leaders is the mass crackdown and incarceration strategy of El Salvador. Since declaring a state of emergency almost two years ago, President Nayib Bukele has virtually eliminated one of the world’s highest homicide rates. Neighboring Honduras is emulating his approach. Ecuador plans a referendum to adopt similar measures.

Mr. Bukele brought peace by locking up 76,000 people – anyone suspected of gang or other criminal activity or association. He is expected to win easy reelection this Sunday, despite changing the constitution to enable him to seek reelection. People say they can take their children to public parks again. Critics say democracy has been trampled. Vice President Félix Ulloa admitted as much on Tuesday but argued that security was the better trade-off for limiting individual rights.

In El Salvador’s other neighbor, Guatemala, a new government is now pursuing a different strategy based in part on countering corruption to restore economic opportunity. The approach is shaped around values that President Bernardo Arévalo cultivated during 25 years of peace building in other countries, such as respect, reconciliation, and individual dignity.

The objective of peace building is “not to create dialogues, but to build societies that know how to talk to each other, that know how to establish agreements, that know how to manage differences,” President Arévalo told the United States Institute of Peace.

Such dialogue has many venues. A local group literally sewing peace into its community is Trama Textiles, a cooperative owned by Mayan women in Guatemala that promotes equality through traditional weaving. It notes on its website that art “fosters affection” and “ameliorates isolation.”

In El Salvador, one church leader has turned his kitchen into a bakery, offering former gang members a way back into society. “Reintegration is nothing more than giving an opportunity to someone who no one else wants to help,” Pastor Nelson Moz told La Croix International last year.

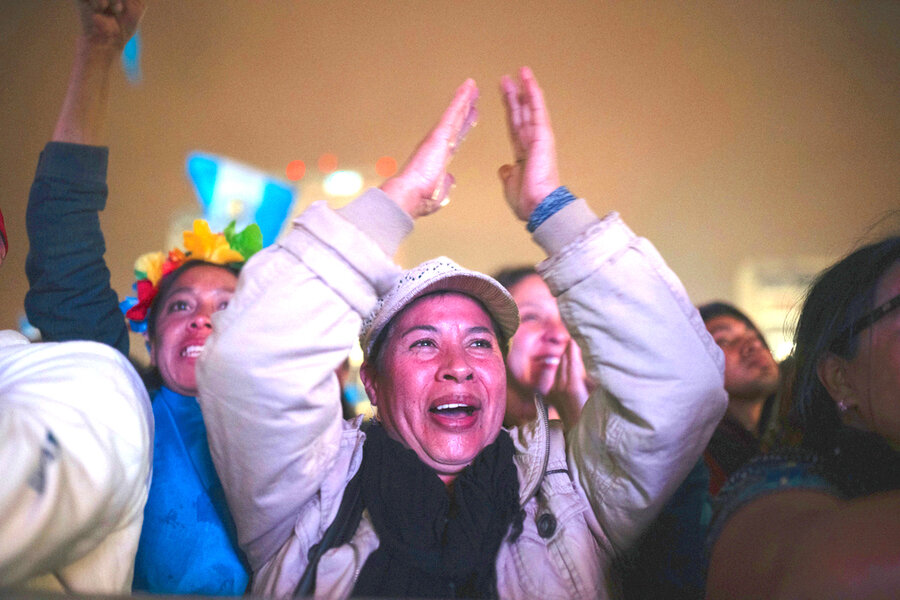

A dialogue is unfolding across Latin America about the best way to build peace through governing.