Paving Mexico’s road to reconciliation

Loading...

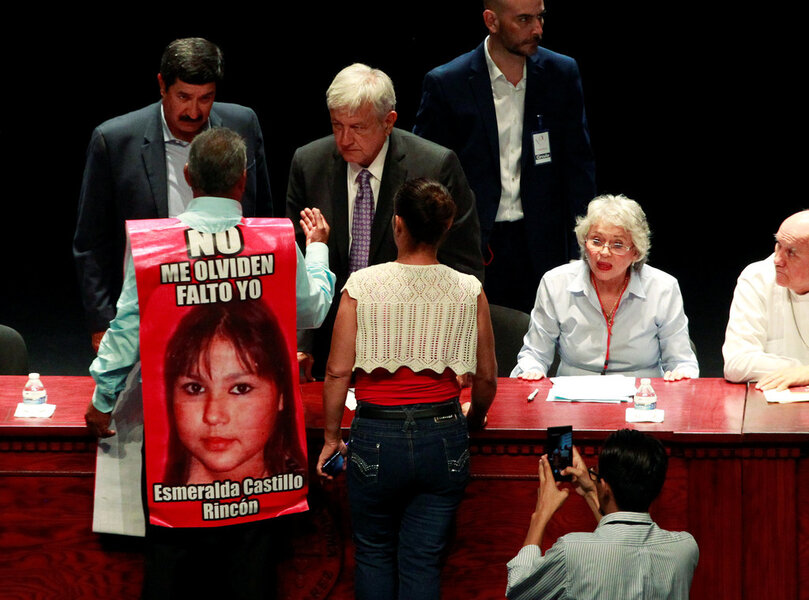

Elected as Mexico’s next president by a wide margin on July 1, Andrés Manuel López Obrador does not take office until Dec. 1. Yet with the homicide rate at a record high, AMLO, as he is known, is not wasting time. In August, he launched a countrywide listening tour aimed at developing a “national reconciliation pact.”

His boldest suggestions include the idea that government should forgive perpetrators who confess their violent acts and commit to not repeat them. It’s part of a broad effort to reform institutions and create new options for youth, including those already seduced by crime.

“You cannot confront violence with violence,” said the president-elect at one “peace forum,” adding, “I respect the people who say don’t forgive or forget. I say, forgive, but don’t forget.”

Offers of official forgiveness have become a common tool in several countries caught up in mass violence, such as Colombia’s war with Marxist rebels, or countries coming out of a long conflict, such as post-apartheid South Africa. AMLO stresses the need for citizens – of every country – to help create the conditions for peace and ensure that the tragedies of recent years are ended and not repeated.

Improving public security, providing justice, and restoring social peace are at the top of his “to do” list. The president-elect hopes the public listening sessions over the next two months will start a healing process. It may also fuel the corrections needed in a country where his election reflected a deep loss of public confidence in the government’s ability to handle violence and corruption.

Since 2014, violent homicides in Mexico have risen steadily. Last year, they reached the highest totals ever recorded (more than 29,000 killed). And over the past decade, more than 35,000 people have vanished, presumably victims of criminal or corrupt officials.

Rising crime has overwhelmed and undermined law enforcement and justice institutions. In the past three years, crime has spread more widely around Mexico. No longer dominated by large drug cartels, crime became “democratized” to smaller, local gangs carrying out a variety of criminal activities, including stealing gasoline from pipelines. Simultaneously, Mexico’s justice system continued to produce very few convictions, despite efforts at reform. Law enforcement institutions are perceived as corrupt and ineffective. According to a 2017 poll, some 76 percent of Mexicans feel unsafe.

During the election campaign, AMLO was vague about how he would deal with these challenges, at one point mentioning “amnesty,” which set off alarm bells about dealing with drug capos and brutal killers. Now he hopes to develop specific proposals with the help of the discussion sessions. He is inviting a full debate that includes all points of view and options, from amnesty and drug decriminalization to ensuring that the guilty are prosecuted.

His advisers stress the importance of supporting victims, including funds to help them and perhaps establishing truth commissions to uncover past wrongs. They suggest radical restructuring the current security model, which mainly relies on police and military forces, to one that improves police capacities and gradually withdraws the armed forces from crime fighting. AMLO also seeks to strengthen justice institutions and cut off cartel finances.

In addition, he proposes more educational and employment opportunities for youths, notably those embedded in low-level criminal activities such as being a gang lookout. The idea is to reinsert them into society, educating rather than punishing them.

None of this will be easy. It will take new laws, new funds, wise policy choices, and a persistent effort to forge new social attitudes. But, with some 65 percent of Mexicans currently expecting security and other improvements under his presidency, AMLO has a good foundation on which to build. It is an effort worthy of support.