Turning children of war into children of peace

Loading...

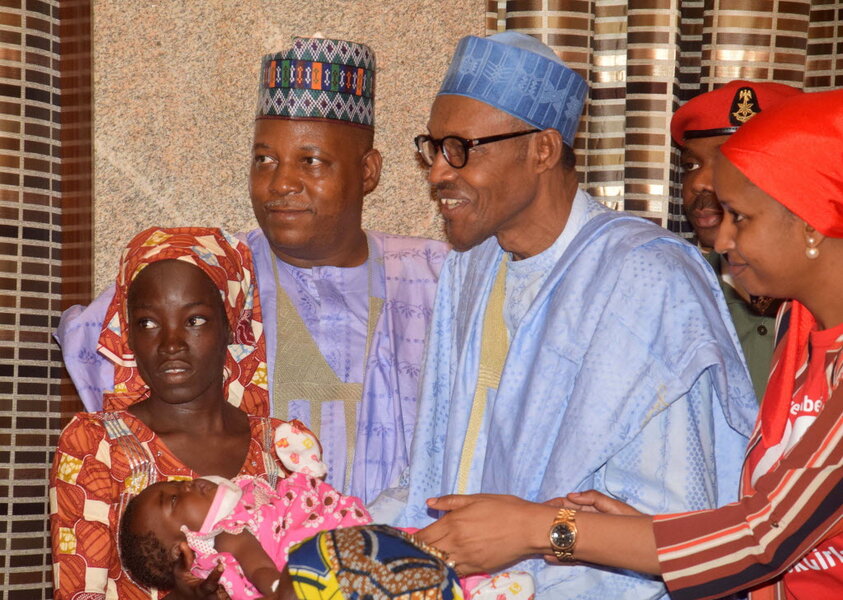

An estimated 19 million children have been caught up in world conflicts, but perhaps the most famous may be Amina Ali Nkeki. She was one of 219 girls abducted by Boko Haram militants in 2014 at the Chibok school in Nigeria, and the only one to be rescued so far. After meeting with Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari on Thursday, the 19-year-old was promised assistance in reintegrating back into society.

Her rescue and recovery should set an example in helping all the other “war children” who have been either kidnapped, abused, forced to flee, or conscripted to act as soldiers. Focusing on the most vulnerable in a conflict is a way to end a conflict. Combatants in a war often find it difficult to ignore pleas to save the young and innocent.

In 2014, for example, the United Nations was able to convince some forces in Yemen’s war on a plan to end recruitment of child soldiers. (The war has since intensified, putting the plan on hold.) In Colombia, the government and the largest rebel group, known as FARC, agreed this month to release child soldiers and provide them assistance to restart their lives. And in the Central African Republic, the UN made a deal last year between several warring factions to release thousands of children trapped in an interethnic and religious war.

Rehabilitating such children requires special skills and resources, especially if they have been trained to be violent. A number of groups working in post-conflict areas have shown good results in this effort, such as War Child, Enfants Sans Frontières, the Children and War Foundation, as well as UNICEF. Children traumatized by conflict can be taught peacemaking skills and social cohesion to counter negative feelings, such as hate. Many are given an education or financial support to start a business. They are taught to take control of their lives and insist on their rights. Most of all, they may learn to forgive or be forgiven.

Such services are especially needed for the estimated 7.5 million children displaced by the long war in Syria. Many have missed years of school unless they live in refugee camps equipped to provide education.

Some children inside Syria have grown up amid regular violence. And in Iraq, according to a study published in the journal Surgery, war violence between 2003 and 2014 was directly responsible for 1 in 6 injuries suffered by children.

As a peacemaking tactic, intervening on behalf of children is a practical way to curb a conflict. It is also humane, a way to embrace not only the most innocent but the idea of innocence as something possible for all.