Computers vs. humans: the electronic brains are the vulnerable ones

Loading...

A recurring theme in science fiction over the past 50 years has been the ever more powerful computer. The story line goes like this: Mankind welcomes helpful new technology but grows increasingly dependent on it. Eventually, technology evolves into a kind of super-brain that enslaves mankind.

Skynet was the cyber overlord in the “Terminator” movies. Mother was the big brain in “Alien.” The most famous was the treacherous HAL in “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

As HAL himself unctuously explained, “I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think that any conscious entity can ever hope to do.”

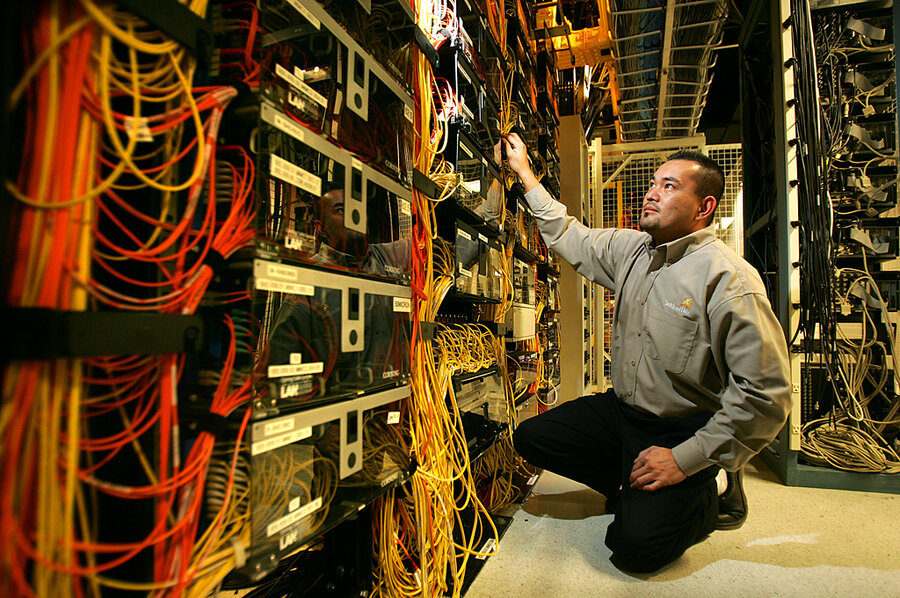

Computers may yet compete with us for superiority. That is for futurists and sci-fi fans to debate. For now, notwithstanding impressive feats such as the “Jeopardy” prowess of IBM’s Watson, computers are really just souped up libraries, speedy accountants, blazingly fast math machines. They regulate electricity, answer basic questions, map locations, and let us connect with each other in ways we never imagined 20 years ago.

They are not (yet) autonomous. But every day we rely on them more.This is why concerns about cyberwar are serious. (See Monitor specialist Mark Clayton’s deeply researched report on cyberwar. Last year, Mark broke the story of the Stuxnet computer virus, which was delivered via thumb drives to computers in Iran, may have damaged the Iranian nuclear program, but may also have now have jumped the fence into the hacker community. Mark also developed a ground-breaking piece on the penetration of the computers of American energy companies – an apparent attempt to gain competitive advantage in bidding for oil concessions.)

Cyberwar is an issue that many of us probably would not rather think about. We sense it, however, every time we stick a bank card into an ATM or upload data to a remote server: What happens if the machines crash? We’re not trying to scare you with this report.

We just want you to be forewarned. Nations the world over are developing cyberwar capabilities. From Cairo to Tehran to Beijing, governments have used an Internet “kill switch” of sorts to control information. Estonia and Georgia have seen hacker attacks that appear to have been launched from Russia.

But those are fairly primitive compared with the possibility of the insertion of a malicious code that degrades or disables a national power grid, plunging modern society into the dark.If the nuclear age brought about a complex set of concerns that didn’t exist in the gunpowder age, the growing threat of cyber conflict will do that in the decades to come.

Cyber specialist James Mulvenon compares 2011 with 1946 in the sense that “we have these potent new weapons, but we don’t have all the conceptional and doctrinal thinking that supports those weapons or any kind of deterrence.” The barriers to entry in cyber warfare are much lower than with nuclear weapons. Individual hackers can easily acquire, alter, and deploy mischievous code.

Disruptive software can come in the most innocent of packages. Stuxnet, for instance, did not sneak into Iran through an Internet firewall. It rode in aboard one of those innocent-looking thumb drives that companies give away to promote their services.

Cyber weapons are hard to trace. Stuxnet, for instance, appears to have Israeli (and possibly American) fingerprints. No one can say for sure. We’ll need new strategic thinking as well as new defenses. We don’t live in the era of the malevolent super-brain. The computers that surround us turn out to be more vulnerable than invincible.

John Yemma is the editor of The Christian Science Monitor