Wisconsin recall election: Scott Walker, Republicans – 1; American democracy – 0

Loading...

| Saint Louis

Were politics baseball, none of this would matter.

Scott Walker and the Republicans took the series in Wisconsin recall elections yesterday. They gave Democrats and Big Labor a drubbing. The breakfast banter over exit polls and who will win the White House in November – no more reliable than insisting the Dodgers will take the World Series because they have the best record in the majors today – would be cream for the morning coffee.

But unlike baseball, politics has consequences, and they run much deeper than how one ballot might tip the next. In one way or another, the Wisconsin experience reflects the wrenching decisions that states under both Republican and Democratic leadership are having to make in the face of ballooning deficits.

But perhaps because of Wisconsin’s long tradition of civility and compromise in the public arena, the bitter recall battle there has brought into sharper relief how our politics are changing structurally and what is being lost.

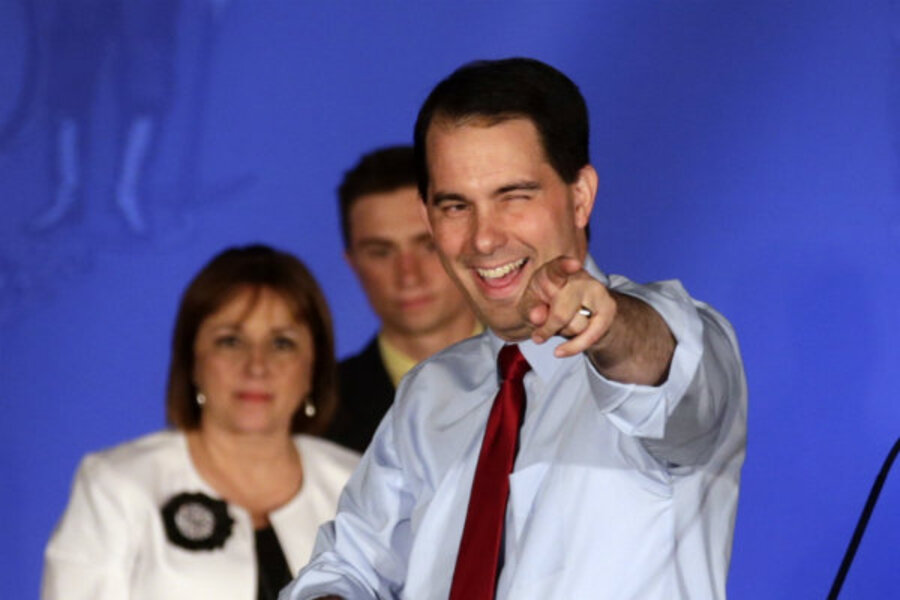

Gov. Scott Walker swept into office in the 2010 tea party wave that also put Republicans in control of the US House of Representatives. Refusing federal stimulus funds for high speed rail development despite Wisconsin’s flagging economy, $2.5 billion budget deficit, and swelling unemployment, he promised to create 250,000 new jobs and jump start growth through fiscal reforms.

Mr. Walker’s primary target was labor. Since the adoption of collective bargaining for public employees in 1959, enrollment in Wisconsin’s public unions grew five-fold, from 7 percent to 36 percent, by 2010.

As a candidate, Walker advocated requiring public employees to pay more toward their pensions. But once in office, he backed a bill stripping the right to collective bargaining over pensions and health care from nearly all of the state’s public unions in addition to tying salary adjustments to the rate of inflation. The unions cried foul.

That policy shift and subsequent underhanded Republican tactics in the state Senate to push the bill through launched the movement to depose Walker, his lieutenant, the senate majority leader, and three other Republican senators.

The recall highlighted one structural change and two trends threatening the American form of self-government.

The first change is the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United vs. the Federal Election Commission, which held that the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting political expenditure by corporations and unions. This year’s election cycle marks the first significant opportunity to gauge the impact of that ruling, and already the change is significant.

It allowed one person – billionaire casino magnate Sheldon Adelson – to almost single-handedly finance Newt Gingrich’s presidential ambitions through the super PAC Winning Our Future. It arguably tilted the playing field in Wisconsin, where billionaires Mr. Adelson, David Koch, Amway founder Richard de Vos, and others poured millions into the recall campaign through various conservative and pro-Walker groups, helping the incumbent build a 7 to 1 funding advantage over his rival.

The second change to American democracy this recall election highlighted is the growth of off-campus legislation-producing organizations. External influence in lawmaking is nothing new, but it is becoming more formal and sophisticated.

The Washington-based American Legislative Exchange Council (known by its acronym ALEC), for example, brings together lawmakers, corporate lawyers, and other stakeholders to draft legislative templates for Congress and state legislatures. Walker’s most controversial education reforms grew out of this process, and the same measures showed up in other states.

The third factor threatening American governance is intransigence. There is a wide gulf between the kind of shrewd political muscle that made Lyndon Johnson an effective majority leader and the oppose-everything approach of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Majority Leader Eric Cantor.

Their hardline stance has filtered out to the states as the tea party flexes its demands for more conservative, more inflexible leaders and candidates. In Wisconsin, Republican state senator Dick Spanbauer, exasperated with his own party, is following Maine Senator Olympia Snow’s path into retirement.

For decades Republicans have cited the 10th Amendment principle of federalism as evidence of the Framers’ intent to limit the role of the federal government by leaving all but a few specified functions – the national budget and defense – to the states. Wisconsin shows how the conservative movement is shifting, evolving its strategy to advance its agenda in the name of federalism.

Fifteen years ago, Republicans in Congress advocated sweeping changes at the federal level – welfare reform, for instance, and dismantling the department of education. Now, they’re chipping away at the institutions they oppose and weakening the diverse constituencies on the left through coherent policy reforms financed and conceived of or enhanced externally.

According to the National Conference of State Legislators, there are now more than 100 bills in process to end collective bargaining. Like similarities occur in education and voter registration reforms across Republican-controlled states.

Against these threats, and with moderates increasingly standing down or voted out, it is hard to see how an ethos of compromise can be restored to American politics. The notion of shared interests seems temporarily, at least, to have been lost. And that may be the value of Wisconsin.

Recalls are rare. In all of American history, Wisconsin’s was the third. They have a taint of something tawdry, or else of desperation. In Wisconsin, people were moved by deep frustration and dismay over the tactics of those they entrusted to govern. More than 900,000 people’s signatures were gathered on the recall petition of Governor Walker. There was a decided sense of the people pushing pack.

We need more Wisconsins – not recalls, per se, but spirited public engagement to reclaim the public square for fair and robust debate. Neither side has all the answers on the urgent challenges that we face. We share the same interests. It should not be this hard to listen to each other.

Kurt Shillinger is a former political reporter for The Christian Science Monitor. He covered sub-Saharan Africa for The Boston Globe and was the security studies research fellow for the South African Institute of International Affairs in Johannesburg from 2005 – 2008.