Beyond Kony 2012, child soldiers are used in most civil wars

Loading...

| Albany, NY

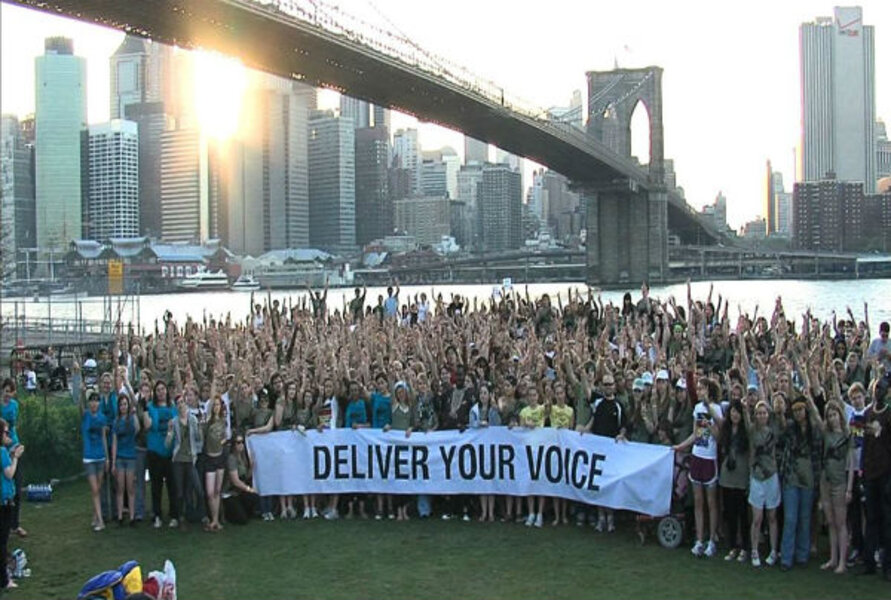

Tonight, April 20, is the Invisible Children organization’s “Cover the Night” campaign, where people all over the world are supposed to plaster their towns and cities with Kony 2012 posters. Invisible Children, the creators of the viral video “Kony 2012,” seek to increase pressure on American policymakers to help capture Joseph Kony, the brutal leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

Raising global awareness about the use of children as soldiers is a noble goal, and Mr. Kony certainly deserves to be brought to justice for the 20 years he spent using child soldiers to terrorize Uganda. While Kony deserves to be punished for his crimes, his arrest alone will do little to address the global problem of child soldiers.

The military recruitment of children by Kony’s LRA is hardly an anomaly. Rather, it is practically the norm for rebel groups and governments alike in civil war and conflict zones around the world.

The Kony 2012 video fails to educate viewers about why the practice of conscripting children occurs and how to prevent it. Our research shows that the use of child soldiers is actually driven primarily by the tactical considerations of government militaries and rebel forces rather than the deviance of individual leaders.

In our global study of 109 civil wars from 1987 to 2007, we find that child soldiers (under 15 years old) were used in 81 percent of those conflicts. Within these conflicts, rebel groups employed child soldiers nearly 71 percent of the time, while government forces employed them roughly 55 percent of the time. Thus, supposedly lawless rebel groups are not the only parties responsible for the use of child soldiers.

The use of child soldiers is not Africa-centric either. Youths have been pulled into numerous battles in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and South America as well.

The reasons children are recruited to participate in civil wars are complex. The hypothesis that child soldiers are brought into conflicts by pathological, predatory leaders addresses only a small piece of the problem. Our research into the tactical uses of child soldiers reveals several key findings.

The first is that the bloodier the civil war, the more likely children are to be drawn into it. Both governments and rebels employ child soldiers to fill their depleted ranks, and often compete with one other over what they see as a resource within the conflict. This treatment of children as a commodity in part explains why both governments and rebels engage in massive forced recruitment campaigns to fill their ranks with child soldiers.

We also find that a number of governmental policies are also strongly associated with whether child soldiers are used in civil wars.

First, the more money governments spend on their militaries as a proportion of their gross domestic product, the more likely they are to recruit child soldiers.

Second, the more extensive governments’ use of political terror is prior to the outbreak of a civil war, the more likely governments and rebel groups will be to use child soldiers.

Last, we find that democratic governments are substantially less likely to recruit child soldiers than authoritarian governments. Taken together, these findings indicate that countries with authoritarian, militant, and human rights-abusing regimes are more likely to use child soldiers during civil wars than liberal, pacifistic, democratic regimes.

Such findings, of course, make sense. But what this suggests is that the problem of child soldiers can be addressed via structural approaches aimed at governments and societies. Tackling the underlying problems in those countries can mitigate the factors that give rise to the use of child soldiers in the first place.

For example, states with a track record of human and civil rights abuses should be held accountable before conflicts start. Directly influencing foreign governments’ human rights policies is obviously difficult. Yet, governments can make it more difficult for human rights abusing regimes to hide their atrocities by calling international attention to those actions and the leaders responsible for them. Part of what can shape leaders’ use of child soldiers is their expectations of whether it will alienate their supporters.

Promoting democratic transitions in conflict-prone countries is another way to reduce the likelihood that child soldiers will be used in subsequent conflicts. Ending Saddam Hussein’s policies on recruiting children into the Iraqi military was certainly one of the positive aspects to come out of Iraq’s democratic transition. The recent international pressure applied to force the coup leaders in Guinea Bissau to step down and let a democratic government return could help prevent child soldiers from being drawn into future conflicts within the country, as they previously had been.

Interceding in civil wars before they become bloody conflicts of attrition can also have a preventive effect. The 1994 genocide in Rwanda is a constant reminder of the devastation from doing nothing. The international community’s inaction left hundreds of thousands dead and allowed the practice of using child soldiers to disseminate into the conflicts taking place in the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo for another decade.

The last recommendation, and easiest one to implement, is for the international community to deny military aid to governments that employ child soldiers. In 2010, for example, the US sent military aid to Chad and Yemen, even though the Obama administration knew their governments used child soldiers. Such aid only encourages this practice and undermines international efforts to stop it.

The underlying factors that give rise to child soldiers may be costly and difficult to address, but they are not intractable. The civil war and the LRA’s reign of terror that roiled Uganda from the late 1980s to 2007 was a tragedy. But limiting our efforts to prevent the use of child soldiers only to that case would be a travesty.

Bryan Early is an assistant professor in the Political Science and Public Administration & Policy departments in the Rockefeller College at the University at Albany, SUNY. Robert Tynes is the research director for the Project on Violent Conflict in the Rockefeller College at the University at Albany, SUNY.