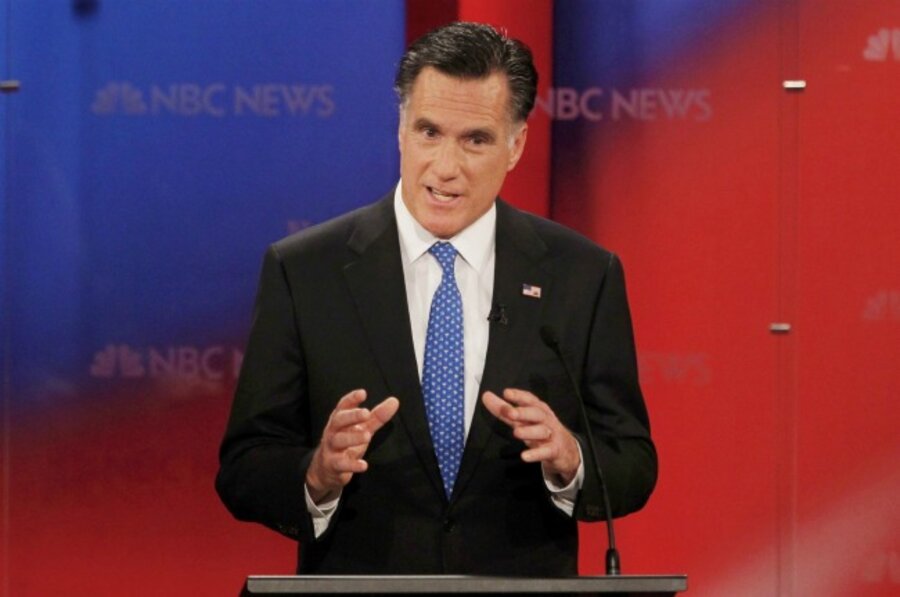

Thanks to Occupy, rich-poor gap is front and center. See Mitt Romney's tax return.

Loading...

| Newton, Mass.

At the town meeting in New Hampshire where Senator John McCain endorsed Mitt Romney as the Republican presidential candidate last month, a questioner shouted: “The US has the highest income inequality in the entire developed world.”

The senator, according to one press report, walked over to the man, and speaking “menacingly” said, “Be quiet.”

Oops, too late, Senator! The secret’s already out: A new survey put out this month by the Pew Research Center finds two-thirds of Americans see “strong conflicts” between the rich and poor – including the majority of Republicans polled – an increase from 2009. The original survey question asked respondents: “In America, how much conflict is there between poor people and rich people?”

Their responses shouldn’t be surprising. The rich have been piling up a bigger and bigger share of the nation’s income and wealth over recent decades – a fact borne out in Mr. Romney’s own tax return, which his campaign released today. Thanks in large part to information disseminated easily on the Web and the ongoing voice of the Occupy movement, Americans now know the income inequality gap well, and don’t like it because they regard it as unfair.

As campaign rhetoric and coverage already show, the distribution of income and wealth will be a prominent issue in the forthcoming presidential and congressional elections.

Under quizzing by the press, Mr. Romney has admitted that he pays an effective tax rate of about 15 percent. (His tax returns show that it’s closer to 14.5 – below average even for millionaires.) This is in large part because the vast majority of his income comes from “investments” (much of them a form of ongoing compensation from his work at private equity firm Bain Capital), which are taxed at the capital gains rate of 15 percent. That’s a rate far less than what many middle-income Americans pay in taxes.

When Republican candidates warn that highlighting the issue of rising income-and-wealth disparity could stir up “class warfare,” they are absolutely right. So far, thankfully, the issue has not prompted any serious violence. The Occupy Wall Street movement has been basically peaceful, aiming successfully to bring to public attention the accumulation of wealth by the top 1 percent of Americans versus the remaining 99 percent. But history suggests a huge rich-poor gap can be a factor leading to political discontent and worse.

One old history textbook, referring to the 1789 French Revolution and its Reign of Terror that cost many of the royal family and nobility their heads at the guillotine, notes “mob violence was the natural outcome of centuries of oppression of the poor by the rich.” The French Revolution had enormous influence across Europe, eventually bringing political, social, educational, and economic betterment for the bottom 99 percent and weakening the aristocracy.

Of course, today’s poor Americans are far better off than the peasants and serfs of old Europe. And Americans nowadays have a relatively calm and unexcitable political character. They also have a higher average income than most citizens of big European nations. But the United States also has a higher rate of income inequality than Europe.

Up to now, the rich aren’t being attacked in a vicious manner, thank goodness. But the mood could change if Republicans continue to insist that taxes not be raised on the well-to-do and that Congress cut government spending benefiting the poor and middle class to reduce the deficit. Certainly the rich-poor gap could cost Republicans many a vote later this year – though not their heads.

So why does this income inequality gap feature so prominently in American political discourse now? For those interested in the economic facts, it is far easier today to find them than a few years ago. That’s largely because a host of liberal Web sites are today providing comments, studies, and news about the rich-poor divide.

As preliminary campaign rhetoric shows, the distribution of income and wealth will be a prominent issue in the forthcoming presidential and congressional elections – for both Republicans and Democrats.

It was a free web product called “Too Much” that mentioned the McCain incident. It’s a weekly email newsletter turned out by the Institute for Policy Studies that reviews inequality matters.

A few years ago such a web site could have been ignored by Washington politicians. But today more citizens are getting their news and views from blogs, aggregate web sites, and social media, while traditional news media – both print and online – struggle to keep their audience.

Even the cautious Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in Paris uncharacteristically speaks of the need to tax the well-to-do in industrial nations.

A study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities criticizes Mitt Romney’s proposal to eliminate major federal assistance programs for low-income Americans and turn them over to the states because the federal bureaucracy eats up most of the money Congress provides. “Simply false,” the study charges, noting that more than 90 percent of such programs as Medicaid, food stamps, housing vouchers, and school meals goes to beneficiaries, not the federal bureaucracy.

Clearly, Americans – thanks in large part to sites like these and the Occupy movement’s persistent message – are more aware of the rich-poor gap. It has become a subject of national discussion and will figure significantly in the election season to come.

David R. Francis is a former Monitor economics reporter and columnist.