US must engage Yemen's real power-brokers

Loading...

| Atlanta

In protest-racked Yemen, the embattled president’s hold over his country has deteriorated to such an extent that he’s euphemistically known as the “mayor” of only one half of the capital city, Sanaa. The erosion of President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s authority must prompt the United States to focus on the true longtime power brokers in Yemen – the tribes.

As has become self-evident in Afghanistan and Pakistan, where central authority is weak or, in Yemen’s case, verging on nonexistent, tribal engagement is an absolute necessity. But throughout Yemen’s recent history, the US State Department has rarely shifted its focus away from Sanaa to Yemen’s rural areas.

One reason for this lack of American diplomatic venturing is security concern about leaving government-controlled urban centers. Yemen’s tribes are indeed heavily armed and skilled with their weapons. On several occasions, they’ve roundly beaten Yemen’s military, each time bringing Saleh’s power into question.

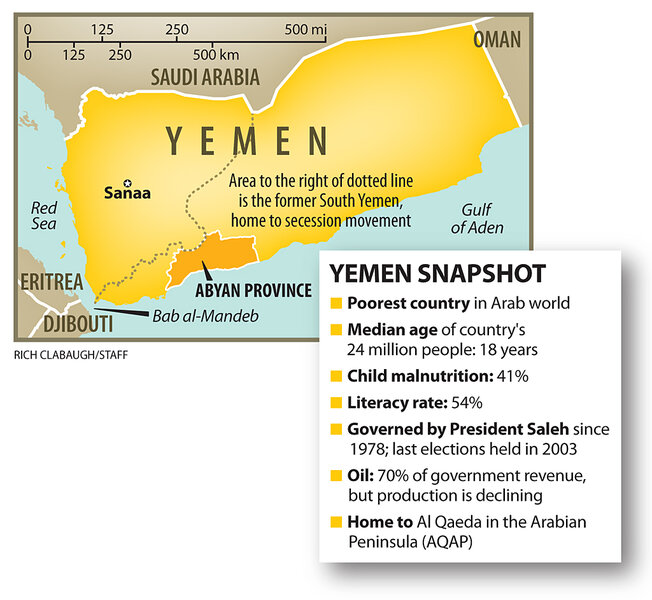

Another concern for US officials is Al Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Many American and Western policymakers believe this terrorist force receives free rein in Yemen’s rural north because of the “lawless” tribal areas there. However, an extensive report by the US National Counterterrorism Center on two rural Yemeni governorates reveals no true or fundamental link between AQAP and Yemen’s tribes – with most of AQAP’s leadership and low-level soldiers hailing from urban areas, even if hiding in the north.

To effectively promote the US interests in Yemen, some young American diplomats are going to have to earn their stripes in the provinces of Marib, Shabwa, and Al-Jawf. Perhaps most importantly, diplomats need to be allowed to chew khat, the leafy, green stimulant chewed by most Yemeni men and women across the country. Any serious negotiation in Yemen is done in a khat chew.

Often incorrectly characterized as a den of bumbling idiots, the US Embassy in Sanaa is home to capable and knowledgeable diplomats and Arabists, many of whom speak excellent Arabic, including US Ambassador Gerald Feierstein. However, these resources are squandered in Sanaa in hopeless negotiations with political parties and regime loyalists.

There is no doubt that some of these diplomats could do effective work outside the capital if security paranoia calmed down. As someone who has traveled in rural Yemen, openly identifying myself as a non-Muslim American, moving about is not as hard as it’s made out to be.

It may be tempting to believe that the future of Yemen lies not with the tribes, but with the youthful protesters in Sanaa who are in their ninth month of an inconclusive revolution. Indeed, the tribes have thrown their support behind the protesters. The most prominent example is Sheikh Sadeq al-Ahmar’s public declaration of support in Sanaa’s Change Square. The sheikh is the most influential figure leader of the Hashid tribal confederation, Yemen’s most politically powerful tribal conglomerate.

While many protesters were quick to embrace tribal support of the urban protest movement, many members of the independent youth movement were less enthusiastic. Calling for a civil state and the rule of law, some protesters want the power of Yemen’s tribes to be thrown into the annals of history. Some even go so far as to call the tribesmen backward, standing against progress and democracy.

But Yemen’s independent youth have yet to demonstrate that they are capable of leading the country into a post-Saleh era of democracy. Lacking a specific plan for government or transition, the independent youth often release series of demands that are platitudinal and idealistic, proving themselves, thus far, to be ill-equipped to handle a transition of power, let alone a new Yemen.

As the political crisis plays out in urban Yemen, tribes will still be the most powerful players in the country. It’s a reality that all sides in the crisis will have to consider when forming a new government. And it’s something the US must consider, too.

In a best-case scenario, a federal system would provide tribes local autonomy while remaining under the rule of law – and give tribes adequate representation in Sanaa. In a worst-case scenario, Yemen will not recover from today’s governance crisis and factions will continue fighting across the country.

In either case, Yemen’s tribes will play a pivotal role in the future of the country. It is in America’s best interest to develop relationships with the tribes and encourage them to negotiate over the country’s future. Diplomats are going to have to literally get dirty to make inroads in Yemen, whether in resolving the government crisis, or countering AQAP.

Jeb Boone is a freelance journalist and former managing editor of The Yemen Times.