Most of China's Communist Party princelings aren't like Bo Xilai

Loading...

| Beijing

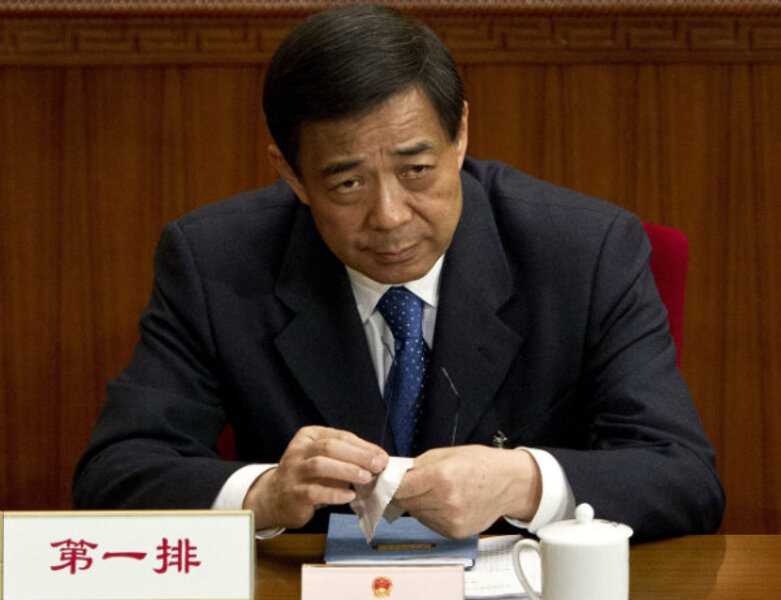

The Bo Xilai saga of power, wealth, corruption, and murder has brought the issue of China’s princelings (offspring of the Communist Party’s former and current senior leaders) to the front and center of the international discourse on contemporary China.

Three underlying assumptions about the princelings drive the noisy speculations about Chinese politics by many mainstream commentators: The princelings form a powerful interest group, akin to a political aristocracy, that exerts decisive influence on China’s political system; their corruption is enormous and sapping away China’s national strength; and their privileges of birth are so vast that they are undermining the party’s legitimacy and destabilizing Chinese society as a whole.

Such assumptions are disconnected from reality and need to be debunked.

Many commentators, including some leading political analysts on China, are framing the princelings as if they are a powerful and unified political block, influencing policies in their favor and pushing for promotions of candidates who represent their interests. There is no empirical evidence to support such a conceptual framework.

If one takes a cursory look at the sons and daughters of China’s senior leaders, current and former, they appear to be living lives ranging from pinnacles of power or wealth to completely ordinary existence, and everywhere in between. Of the ones who have made it to the upper echelons of wealth or power, their economic interests are widely disparate and in some cases competitive to each other’s.

There is no indication that somehow they have coalesced to promote a coherent political agenda. In fact, the very few who have become vocal on politics are voicing very different and even opposite views. Princelings who are climbing the party’s political ladder engage in fierce competition among themselves no less intense than anyone else.

No doubt the princelings are formidable players in both politics and business in part because of their connections. But they are nothing like the landed aristocracy of pre-industrial Europe or the oligarchs of post-Soviet Russia. The former possessed enormous political, social, and military power amassed through centuries of accumulation; the latter came to control a vast portion of Russia’s entire economy.

Just as influence peddlers everywhere, many princelings trade on their connections and are corrupt. Some of them are even stupid enough to flaunt their unlawful or unethical gains by conspicuous displays of wealth. It is a near certainty that Mr. Bo’s case will not be the last, or even the biggest.

But many more princelings do live ordinary lives. Among the ones who are successful, many have indeed excelled on merit. Vice President and heir apparent Xi Jinping is a case in point. His father was a senior leader but was purged by Mao when Mr. Xi was still a child. The younger Xi paid a price for his father’s political downfall and began his career at the lowest level of government service in the villages.

The rehabilitation of his father came only after the younger Xi had moved up the ladder through apparently only hard work and merit. His track record since, from mayor to governor to provincial party secretary and now to the Politburo Standing Committee, has been by all accounts exemplary.

There is no question that princelings enjoy privileges, as do descendants of power and wealth in any other country. But their influence does not come close to holding the political system or the economy captive. On the contrary, upward mobility, both political and economic, is the underlying force of China’s vitality.

The current Politburo, the country’s highest ruling body, consists of 25 members. Only five of them come from backgrounds of power. The remaining 20, including the president and the premier, come from completely ordinary families. In the larger Central Committee, those with privileged backgrounds account for a much smaller percentage.

Compared to ruling institutions of many other countries, such as the US Senate, the party’s top organ is surprisingly short of those from special privilege. In fact, in the party’s 90-year history, and the 62 years of the People’s Republic, Xi will be the very first leader who is a descendent of a senior leader – and this one came through the ranks, overcoming significant personal adversity.

In economics, if one goes down the list of China’s richest, a vast majority of them are entrepreneurs who started with nothing.

Abuse of privilege breeds anger in any society, and China is no exception. Frustrations expressed on the Internet demonstrate such resentment. But Chinese society in general is rather sanguine about the privileges of princelings and the newly rich alike. Perhaps it is a sign of maturity.

It is only a fact of life that those who are born into situations of wealth or power enjoy a degree of advantage to the rest. Some such advantages are even institutionalized, such as legacy admission programs at US Ivy League universities. Only the most radical societies seek to equalize all with brute force, and they did not end well. Jacobin France, Peronite Argentina, and China’s Cultural Revolution come to mind.

A healthy society exercises moderation and tolerance towards privilege as long as mobility is sufficient, which is certainly the case for contemporary China. As such, most princelings would continue to enjoy their birth advantages. The few who abuse their privileges and behave as if their good fortunes are entitlements do great damage to themselves. But the notion that they have held the Chinese state hostage is a total myth.

Eric X. Li is a venture capitalist in Shanghai.

© 2012 Global Viewpoint Network/Tribune Media Services. Hosted online by The Christian Science Monitor.