Finding humanity behind the headlines

Loading...

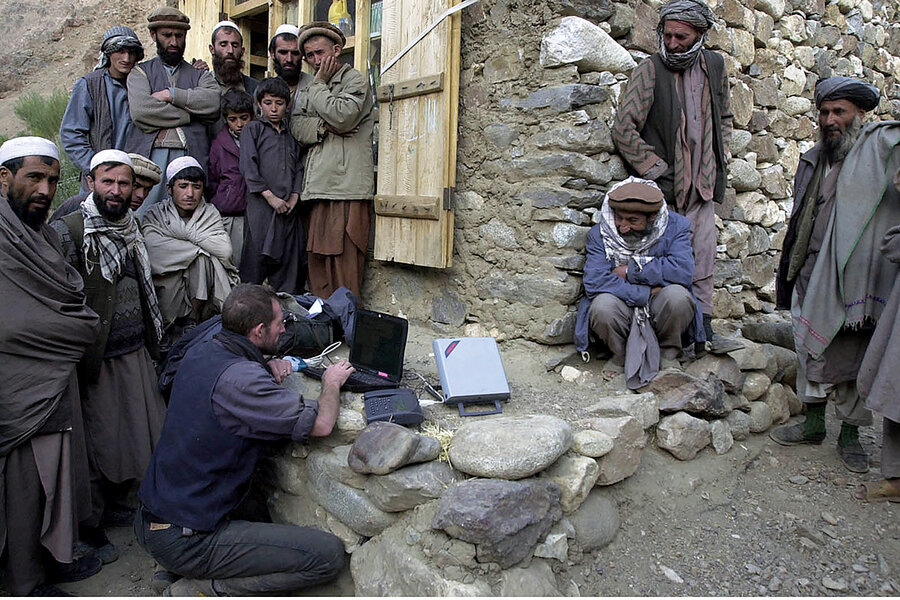

Longtime Monitor correspondent Scott Peterson knows Afghanistan better than most. He’s been covering the war-torn country for two decades.

This week, Scott brings to light a story from Kabul that stems from a trip he took two years ago. On the surface, it’s a familiar tale: the assassination of a judge gunned down in the street by Taliban recruits. But to Scott, Judge Qadria Yasini was more than a political target. She was the mother of a teen who had once jostled for Scott’s attention during a reporting trip to a school north of Kabul.

Scott’s visit in 2019 had been brief; he hadn’t wanted to disrupt the school day.

“But out of the blue comes this young man who spoke great English,” Scott says of his first encounter with Wali Yasini. The 15-year-old had been teaching himself English and seized the opportunity to have his first conversation with a foreigner. “He was almost beside himself,” recalls Scott.

Impressed by Wali’s eloquence and enthusiasm, Scott jotted down his name and phone number and the two struck up a correspondence. Wali shared some of his art (“He really is an accomplished artist,” Scott says) and his aspirations to study in the United States. At one point, Scott helped him vet, and avoid, a dubious program that promised to help secure a U.S. visa for thousands of dollars.

So when Scott realized it was Wali’s mother who was assassinated in January, the news hit hard. It spoke to one of the aspects of conflict that journalists work so hard to convey: that behind every bombing and every tactical strike are people simply trying to live their lives.

“Afghanistan is full of these kinds of stories,” Scott says. It is through this “crucial prism” that he has always approached coverage of a war zone, whether in Somalia, Iraq, or Afghanistan.

Scott first visited Afghanistan in 1999, when the Taliban harshly ruled the country. Two years later, shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks on the U.S., he and several other journalists made their way into northern Afghanistan via Tajikistan – by air, armed convoy, and some trekking – to await the fall of the Taliban in a village north of Kabul. As Northern Alliance forces approached the capital and reports of fleeing Taliban emerged, he found his way into the city to witness the deep emotion of liberation, from the raw anger of a vengeful mob to the “complete joy and jubilation” on the uncovered faces of women celebrating a wedding in public.

Afghanistan is known as the graveyard of empires, a tactical quagmire that has for more than a century ensnared first the British, then the Soviets, and most recently the Americans. “And yet,” Scott says, “in its heart you’ve got these incredibly powerful personal stories taking place. You have this entire society on both sides of the ever-moving front line, and they are forever making calculations about their lives and their future and their safety.”

That, in essence, is the heartbeat of Monitor journalism, the humanity behind the headlines.