Global economic reality check: beyond doom and gloom, a quiet boom

Loading...

Between rising debt levels in the West, political tumult in the Middle East, and rapidly growing economies in Asia, major corporations are anxious about global markets. To gain clarity, many turn to professional forecasters such as Robin Bew. He's the editorial director and chief economist for the prestigious Economist Intelligence Unit (a research and analysis service offered by The Economist Group, which also publishes the weekly magazine The Economist.) I spoke with him last week in Cambridge, Mass. The following are edited excerpts from our conversation.

On the state of the US economy:

We’re in a probably slightly better place than we thought we’d be 18 months ago. The jobs market is not anything as robust as we would like. The unemployment rate is much, much worse than you would generally hope it to be at this point in a recovery. But given the depth of the financial crisis and the scale of the policy response, actually growth is pretty good.

When we look out a bit further, there are clearly lots of things over here that worry us: the level of debt we see in America, and the unsustainability of the government’s finances particularly.

Our view, when you look out over a 5-to-10 year horizon, is that [the United States] is not going to feel quite the way it did over the previous couple of decades. People will be saving more, they’ll be spending less, government will be forced to be quite a bit more parsimonious. We need to get the deficit under control.

When we look at America, we say, "Pretty good policy response, dug the economy out of a hole," but there is a big hangover that needs to be dealt with, and dealing with that will hold growth back here for quite a long period.

On grading the Obama administration’s economic policies:

You have to dial it back a bit and think about what happened under Bush as well, because a lot of the serious, heavy lifting – the emergency response – was done under him. I’d say for both of them actually, I’d give them a “B.” The reality is you never have the counterfactual. You don’t know what America might have looked like if they hadn’t taken the action they did. But I have to say that most economists have a pretty good idea, and it doesn’t look very nice. The reality is, the fact that we can sit here and the economy is not in recession – it’s moving forward, jobs are now being created – that was not a done deal. That was not inevitable. It could have been a lot worse.

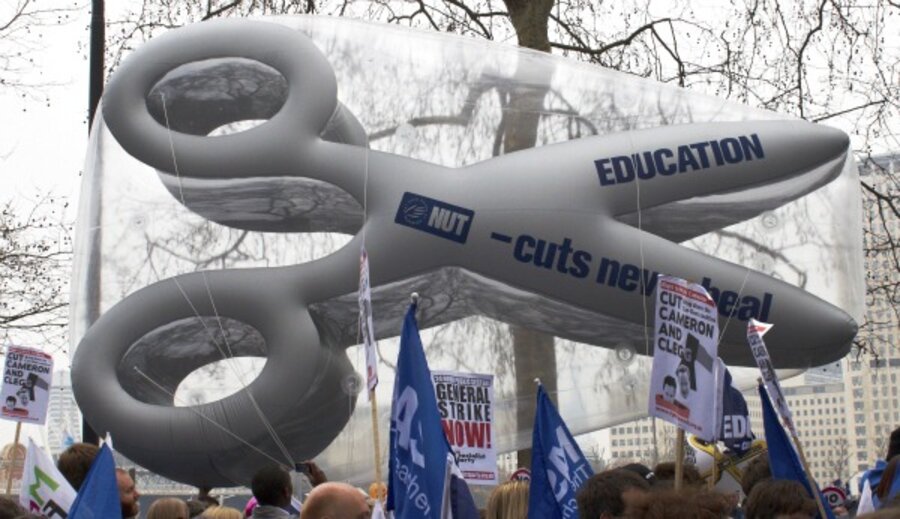

On Britain and America taking different approaches in the face of high debt:

The UK is enacting a very aggressive consolidation strategy –- but that’s just decent words for various spending cuts. One of the things that’s important to recognize is that in the UK, when you’re in power, you can do what you like – you have complete control. In America, it’s not like that. Obama is not a free agent. What actually happens here is determined in large part by Congress. That’s one important difference. Britain can do stuff that would be difficult to do here.

Britain has a lot less room for maneuver. Almost no country in the world has the room for maneuver that America does. And that forces other countries to behave differently. Portugal has no choice, because no one is going to lend to it right now, so they have to cut spending.

In the long run, the chickens will come home to roost. Ultimately, if America looks as if it’s never going to get its accounts in order, people will gradually move away [from buying US debt] and you’ll see other asset classes becoming more important.

Republicans are clear that there need to be cuts but pretty unrealistic about where they need to happen. And Democrats – well it’s actually quite unclear what they think. The things that they hold dear are really the only things that you’ve got left to cut. This is one thing that worries me about America over the longer term. There is no sense of a national debate going on around where these very inevitable spending cuts are going to have to fall.

There are always people in Congress that are level-headed and open to those strategic conversations, but there are not enough of them to make a difference. I wouldn’t like to think that it’s going to take a crisis to get a change, but unfortunately, I think often in America it does take a crisis to get a change.

On the need for budget adjustments:

It’s not really about the next 10 years, or this year’s budget, as much as having a long-term strategy that puts things under control.

In the UK, the thing that’s very important, is not that this year’s budget is going to be very harsh, it’s this idea that there’s a plan, and in 5 years time, it’s going to look very different in Britain. There’s a sense of direction and purpose, and that’s where we’re going to go. And that’s what’s lacking here.

On Chinese-style capitalism:

It’s misguided to think that economic management is their big advantage. I don’t think that’s the case.

China could be so much more than it is today if those [small, entrepreneurial] businesses were deemed to be by the government a legitimate part of the process. From an economic perspective, China could be a much more diverse, much more robust, and possibly much wealthier society if the government was willing to embrace those bits which are intrinsically more difficult to control. Of course a lot of government policy over there is about control. China has been very successful not because of the way the government operates, but actually despite the way the government operates.

China is portrayed as being a very centrally planned economy, but actually China is quite a decentralized economy. Regional government is extremely important. There’s a lot of cronyism. A lot of corruption is happening at the local level. And decisions are not made in the context of a kind of bigger economic strategy.

China’s central government has recognized that corruption gets in the way of success. What they are doing is making examples of people. But what they haven’t really managed to do is change the psychology – which is what they’re trying to do – at the local level.

The central government doesn’t have the degree of control over the way that economy runs that people in the rest of the world often think they do.

On whether the Chinese economy could collapse:

I think a meltdown scenario is unlikely. A slowdown – I think a slowdown is already happening to some extent.

On the global economy’s 'good news' stories that the media are missing:

The big story of our time – and this has been true for about a decade now – is this relative rise of the emerging markets and particularly Asia. Often, particularly in Western media, there is an acknowledgment that this provides an opportunity, but it’s broadly dealt with as a threat. The rise of Asia in particular is viewed as a very frightening thing. And a lot of policy – American policy, European policy – toward Asia is partly around trying to contain that threat.

But I think the good news story is this: Essentially what’s going on is that there’s a couple billion people who were basically not active in the global economy – and by that I also mean living pretty appalling lives – are moving into the broad economic mainstream. And you see this tremendous improvement in the lives and the welfare of huge numbers of people around the world. So if you look at what’s going on in China and what’s going on in India, you go back 15 years and you’ve got hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of millions of people eking out a living on the land, absolutely destitute who now have a standard of living which doesn’t look anything like the one we’d experience in the West but is infinitely greater than anything they’ve experienced before. And that’s a very uplifting story.

In the narrative around the threat that a rising Asia faces, those people who are being sucked into the world economy are doing two things. They’re entering factories and they’re making stuff and they’re selling it over here. There’s a real sense that that’s putting a lot of Americans out of work, or Europeans out of work. That’s causing a lot of angst. And you can completely understand that.

The other thing that it means, of course, is that there’s a couple billion consumers in the world who weren’t there before. And that provides the opportunity. So, the threat, if you like, is the fact that things that used to be done over here will now be done over there. But the opportunity is, there’s two billion people who weren’t buying anything before who are now trying to buy stuff. And that’s the thing that business is very focused on. But the political debate hasn’t really caught on to that.

Ten years ago, all of our clients in China were in China because they could get cheap labor and they were making stuff in China and all that stuff was being exported back to the States and Europe. Now, almost all our clients who are in China are there because they’re trying to sell stuff to the Chinese.

This tremendous improvement in the lot of people in countries who previously had a terrible existence actually goes hand in hand with this enormous opportunity for business around the world to prosper on the back of that. But that message tends to be drowned out by the other message, which is that China makes loads of stuff and it displaces jobs over here.