What are the consequences of a financial transactions tax?

Loading...

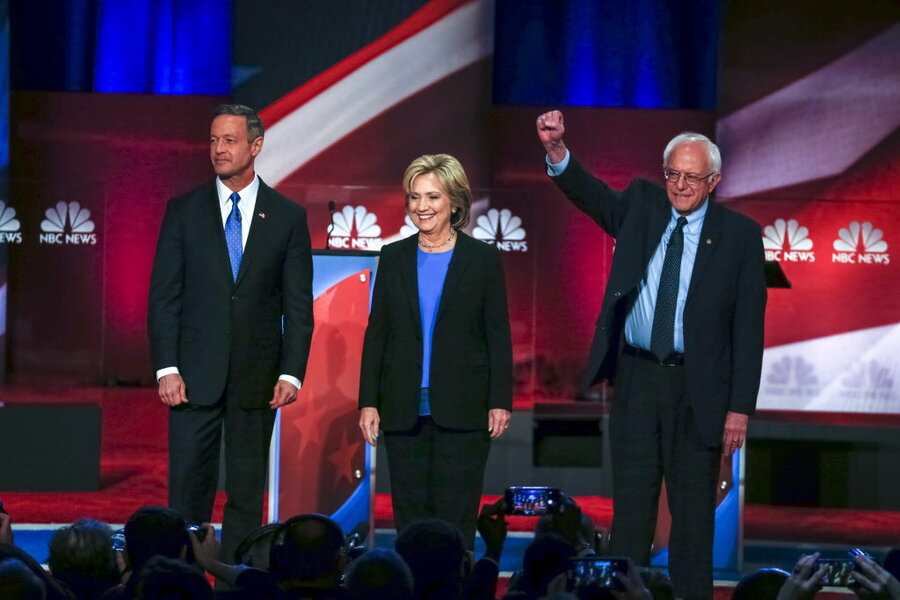

All three Democratic presidential hopefuls, Hillary Clinton, Martin O’Malley, and Bernie Sanders, have proposed financial transactions taxes (FTTs). But could such a levy raise much money and reduce financial sector risk, as their supporters hope? Perhaps, according to a report by my Tax Policy Center colleagues. But if not carefully designed, the tax could do more harm than good to the financial markets and raise much less revenue than proponents hope.

A well-constructed tax could generate about 0.4 percent of Gross Domestic Product in new revenues (about $75 billion in 2017). The paper’s authors, Len Burman, Bill Gale, Sarah Gault, Bryan Kim, Jim Nunns, and Steve Rosenthal, figure the revenue maximizing rate would be about 0.4 percent.

The idea of an FTT has generated plenty of interest around the world. Ten European nations have agreed to enact such a tax starting next year, though they may not make their self-imposed deadline. And several bills have been introduced by congressional Democrats.

Yet, the claim that such a tax would reduce price volatility is controversial. An FTT would certainly reduce trading. But while it would cut unproductive speculative transactions and profiteering (think Michael Lewis and Flash Boys) it would also discourage the trading that keeps prices in line with fundamentals. Some collateral market damage is likely at the rates proposed by members of Congress, which range from 0.03 percent (or 3 basis points) per transaction to 0.5 percent (or 50 basis points).

As with any excise tax, the FTT is built with an internal tension. The more it succeeds in discouraging securities transactions, the less money it will generate. Backers need to decide which is their highest priority. And they need to take care that the tax does not discourage the very transactions that make financial markets efficient.

Some studies suggest that slowing the reaction of markets to new information would increase volatility since prices would have to move more significantly before traders—faced with the new tax—respond. Backers of the FTT may be right when they claim it would discourage speculation, but the tax could just as well increase volatility.

For Clinton and O’Malley, the tax would be just one element of a broader effort to mitigate financial system risk. Both say their tax would be aimed at high-frequency trading, which they say adds volatility to markets. Sanders has a somewhat different focus: to “reduce the economic and political power” of Wall Street and help pay for his plan for tuition-free college education. Thus, his tax base could be much broader than Clinton and O’Malley.

The base is key. Would such a tax apply to just equities and derivatives or also include bonds and foreign exchange? There is an enormous difference. TPC projects about $49 trillion in equity transactions alone in 2017 while 13 times as much, $659 trillion, would be in the broader base.

The paper looks at three different rates, 0.01 percent, 0.1 percent, and 0.5 percent. Not surprisingly, the bang for the buck declines as the rate rises since trading would dry up at higher rates. As trading declines, so does additional tax revenue.

Who would bear the burden of such a tax? This too is a matter of controversy. Because TPC assumes that it mostly falls on investors rather than workers, three-quarters of the tax hike would hit those in the top 20 percent of income.

Like any tax, the FTT has its downsides. Supporters need to design it in a way that minimizes those distortions. For their part, critics need to identify revenue sources that are less troublesome, which may not be easy.

This article first appeared at TaxVox.