Bush's tax plan would add $6.8 trillion to the national debt

Loading...

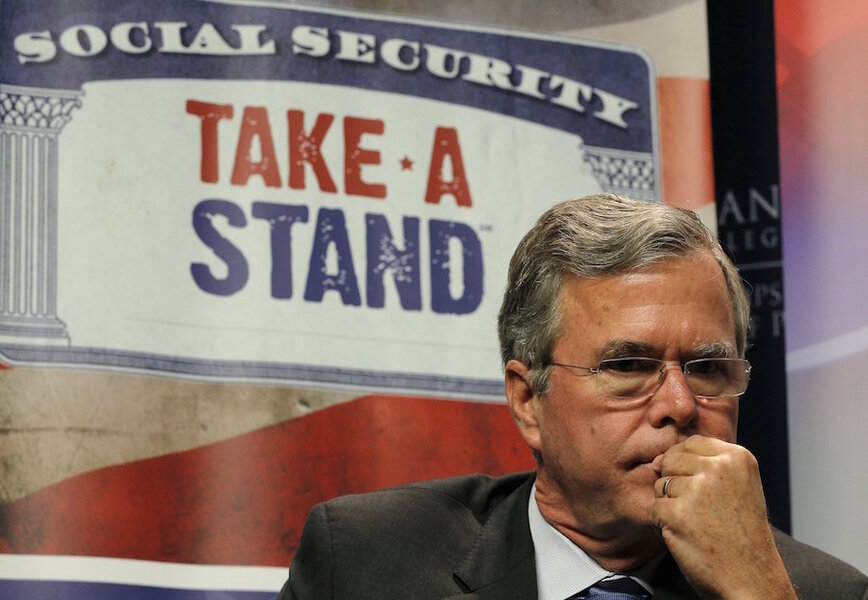

Jeb Bush’s tax plan would boost deficits by $6.8 trillion between 2016 and 2026 and overwhelmingly benefit the highest income taxpayers, according to a new analysis by the Tax Policy Center. With added interest costs, the plan would boost the national debt by more than $8 trillion by 2026. After two decades, TPC figures it would increase the debt by $22 trillion and increase the ratio of debt to Gross Domestic Product by more than 50 percent.

TPC found that in 2017, nearly all households would enjoy tax cuts under Bush's plan, averaging about $2,800. However, the top one percent (those making $737,000 or more) would see their average after-tax incomes rise by nearly 11 percent—or more than $167,000-- while middle-income households would receive an average tax cut of about $1,500, or 2.7 percent of their after-tax income. The lowest-income households would see their after-tax incomes rise by an average of $185, or about 1.4 percent.

TPC’s revenue analysis assumes that people and firms change behavior in response to tax changes, but does not attempt to calculate macroeconomic effects (dynamic scoring).

The plan includes provisions aimed at reducing the cost of capital, equalizing the tax treatment of debt and equity, and increasing the after-tax returns to savers. Taken as the whole, these measures could increase savings and investment and boost the overall economy. However, unless these enormous tax cuts are somehow offset with equally large spending reductions, they’d substantially increase government borrowing and drive up interest rates, thus neutralizing their economic benefits. So far, Bush has not described what specific spending he’d cut to pay for his tax plan.

Bush would collapse the current seven individual tax rates (with a top rate of 39.6 percent) to three rates, 10-25-28. He’d repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax and the estate tax, eliminate much of the marriage penalty, and end the employee share of Social Security taxes for workers older than 67. He’d also dump the existing limits on itemized deductions and personal exemptions that hit high-income households while at the same time adding new limits on those tax preferences.

He’d increase the standard deduction from today’s $12,600 to $22,600 for married couples and from $6,300 to $11,300 for singles and increase the Earned Income Tax Credit for adults with no children. Investors would pay a top rate of 20 percent on capital gains, dividends, and interest income.

The plan would also eliminate the deduction for state and local taxes and cap the value of most other deductions at two percent of Adjusted Gross Income. Charitable gifts would continue to be deductible, but only for the handful of taxpayers who would still itemize under the plan.

Bush would cut the top corporate rate from 35 percent to 20 percent but eliminate most business tax breaks (except for the research credit). He’d allow full expensing of investment in both equipment and structures while ending the deduction for interest costs, a big step towards a business-level consumption tax. He’d shift to a territorial tax system where the US, like most other countries, exempts its multinationals from tax on foreign-source income. However, he’d impose a one-time 8.75 percent transition tax on existing unrepatriated foreign income of US firms, payable over 10 years.

TPC’s $6.8 trillion estimate of the cost of the Bush plan is nearly twice as high as a projection issued by a group of Bush supporters. They figured his plan would add $3.4 trillion to the debt under traditional budget scoring or $1.2 trillion with dynamic scoring--assuming the tax cuts boost the economy by 0.5 percent annually.

The TPC estimate is also much higher than that of the Tax Foundation, which projected the Bush plan would add $3.7 trillion to the debt under traditional budget scoring and $1.6 trillion using dynamic scoring. What accounts for the difference? In part, it’s because the Tax Foundation left out of its analysis provisions that would add about $900 billion in deficits. The bulk of the difference, however, may be because the Tax Foundation assumes that tax rate cuts generate much bigger increases in taxable income than TPC does.

The Bush plan includes some important ideas for increasing savings and investment, simplifying the tax code, and curbing tax avoidance. However, it would add trillions of dollars to the federal debt, largely by lavishing big tax cuts on the highest-income Americans and U.S.-based multinational corporations.

This article first appeared at TaxVox.