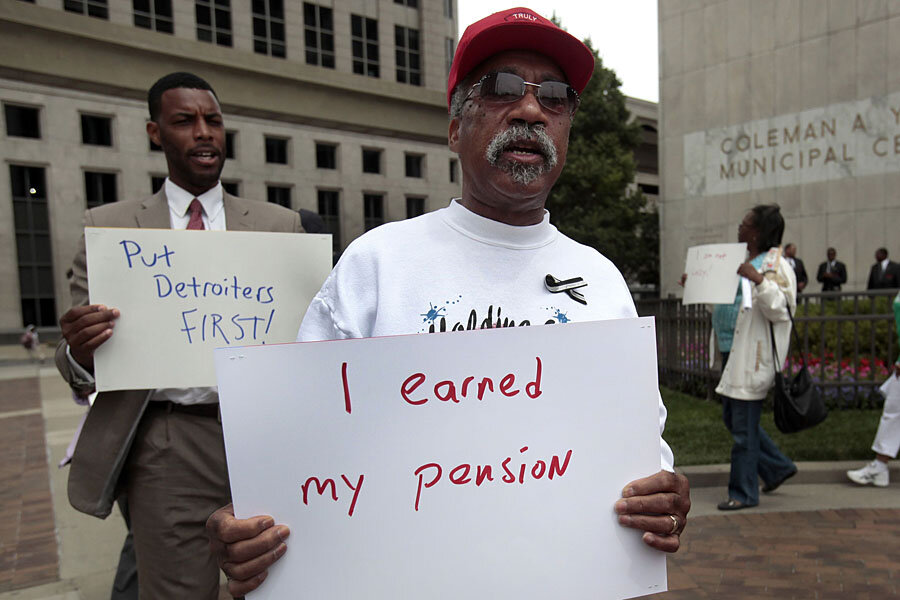

How can states fix $1 trillion in underfunded pensions?

Loading...

Last week’s federal court ruling in the municipal bankruptcy case of Stockton, CA highlighted the enormous challenge faced by local governments with underfunded public pensions. There are ways out of this vise, but none are easy, and all are fraught with risks.

State governments face at least a $1 trillion gap between pensions promised to their employees and retirees and the funds set aside to cover these liabilities. Add the nation’s cities and counties and you get another roughly $500 billion in unfunded promises. Of course, state and local governments don’t have to pay this tab immediately, or even over the next few years. But in places like Michigan’s shrinking cities or in towns that were casualties of California’s housing bust, pensions (and retiree health care costs) are already squeezing budgets for valued services like police, fire, roads, and libraries.

Pensions and other retirement costs pose special problems for local governments. While moving across state lines is a drag (and so called tax migration is likely overstated), taxpayers can easily bail out of cities in fiscal trouble by moving to the next town (assuming it is not also in dire financial straits). At the same time, people moving into a fiscally troubled community may demand lower home prices to offset anticipated higher future tax bills, shrinking the property tax base and making the pension funding problem worse.

As municipalities confront these legacy costs, the paramount question is: Who will be left holding the bag? In a federal court last week, we got a sneak peak at the answer. Echoing findings in Detroit and Central Falls, RI, Judge Christopher Klein ruled that Stockton, CA could cut pensions as part of its bankruptcy resolution. Note that he did not require the city to do so, and it has no plans to take such a step. Klein’s decision is both big and small.

It’s big because it suggests that pension promises once seen as inviolable are, in fact, not.

But his decision is also small because it was issued verbally and not in writing. That means that, at least for the time being, there is no ruling to appeal to a higher court. Even a definitive judgment would be only informative and not binding on other municipal bankruptcies – and most relevant in California. And keep in mind that, breathless rhetoric aside, there have been and are very few pending municipal bankruptcies.

The judge’s comments however, raise a larger question: What are cities in pension trouble supposed to do? Klein concluded that CalPERS – the behemoth state fund arguing on behalf of local pensioners and itself– was just another creditor rather than an arm of the state. He also noted that, hypothetically speaking, cities could contract with a private insurer to provide pension benefits, join a multi-employer plan administered by a private sector union, or offer no pension plan.

The first option sounds similar to the Secure Annuities for Employee (SAFE) Retirement proposal that Senator Orrin Hatch put forward earlier this year. The Hatch plan – essentially to allow private insurers to bid on fixed income life annuity contracts for public workers – received favorable marks from my Urban Institute colleague Richard Johnson. However, it was met with predictable controversy about whether, say, AIG was better situated than state and local governments to manage costs and bear risks.

The second option sounds a lot like multi-employer plans covered by the Public Benefit Guaranty Corporation. But according to the latest PBGC annual report these plans are not doing so well, largely because of the same declining worker-to-retiree ratios that a lot of cities face. The result: many retirees and the federal government are left exposed to considerable financial risk.

According to Stockton officials, the third option is no option at all. City leaders have already said they have no intention of cutting, much less eliminating, pensions because they view these benefits as an important recruiting tool. One might argue, however, that higher current wages are a more alluring than future benefits, which may in fact prove elusive. (City officials may also be intimidated by CalPERS’ exorbitant exit fees, but that’s another story.)

So, what can cities and counties do to protect their workers’ pensions? I’d impose a one-time charge reflected on property tax bills, much like a special assessment in a condominium or homeowner association. Just like when pipes burst or the roof leaks, there’s no choice but to fix a city pension shortfall and everyone – including taxpayers, bondholders, retirees, and current employees – will likely have to pitch in.

Spread over a large enough tax base, the one-time charge could be minimal. For example, according to aMoody’s analysis, total unfunded pension liabilities plus locally accrued debt amount to only 1.7 percent of statewide assessed values. And if the charge were linked to property values, homeowners who have the most to gain will also pay more. (Of course this might be impossible in Proposition 13-limited California.)

The main problem with my solution is that it requires tapping into that larger tax base. This is where higher levels of government like states and feds would have to lend a hand. Of course, they may demur. And there are problems with shifting costs to residents of other cities, although arguably they would benefit from avoiding their neighbor going belly up and some may be even be former Stocktonites who consumed all those services back in the day.

I never said it would be easy.

The post It’s Not Easy to Escape the Local Pension Vise appeared first on TaxVox.