IRS and the Tea Party: A small but bungling scandal

Loading...

The IRS’s botched processing of requests for tax-exempt status by political groups isn’t the new Watergate. It is, in fact, as scandals go, it is barely the Days Inn–based on what we’ve learned from a much-anticipated report by the Treasury Department’s Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA).

That any report by TIGTA is much anticipated says something about Washington these days. This one, a detailed look at how the IRS seemingly targeted tea party and other conservative groups for special scrutiny, found bureaucratic bungling and a troubling bunker mentality up and down the agency.

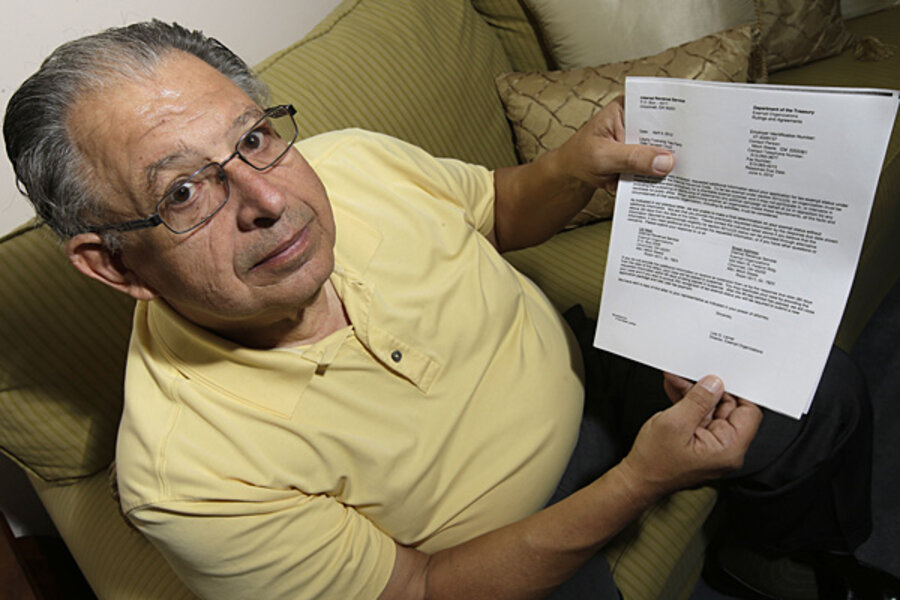

The cost to groups seeking tax-exempt status was not insignificant, and is troubling. TIGTA confirms that some conservative organizations were singled out for special scrutiny and faced burdensome requests for information and long delays before approving requests (though it should be noted that delays are common at the IRS). At the very least, this raises questions about fairness and impartiality from an agency that must be above reproach.

Yet, despite dark conspiracy theories, TIGTA found no evidence of political meddling. Despite allegations that the agency singled out tea party groups for special scrutiny, of the nearly 300 cases the IRS labeled potentially political, only one-third were identified as tea party or other conservative organizations. And not one of those 300 cases, including the conservative groups, had its application for tax-exempt status denied, though some are still pending.

However, the TIGTA report also seems to confirm a long-standing unwillingness by top IRS officials to publicly acknowledge the mess. As often happens in Washington, the coverup may turn out to be far more problematic than the “crime.” There is some irony afoot when the same government agency that demands full transparency from 150 million taxpayers stonewalls requests for information about its own operations from Congress and news organizations.

Here is the outline of the story: From 2010 to 2012 the number of applications for 501(c)(4) tax-exempt status doubled, from 1,700 to 3,400.

While (c)(4) status was created 100 years ago for civic leagues and other community organizations, it became a valuable tool for political organizations in recent years. One reason: It allowed groups to collect money from contributors without disclosing the source of those funds.

The test for (c)(4) status is a difficult one: A group’s primary purpose must be enhancing the social welfare. It may engage in some political activity, but this may not be its primary role. The law does not clearly describe political activity.

In March and April of 2010, mid-level IRS staffers began screening groups with names that sounded “political” such as tea party. By May, agency staffers were told “to be on the lookout” for, among other applications, requests by groups with political-sounding names, such as tea party or patriot.

When the director of the Exempt Organizations office, Lois Lerner, learned of these activities in June, 2011, she ordered that the criteria be changed. The guidelines were somewhat revised in July, but then largely restored by the team reviewing the cases. In the end, it took 18 months for the agency to finally get staff to change its policy of focusing on political views of organizations.

The result: Conservative groups were required to answer wide-ranging and often unnecessary questions, 80 percent of applications were open for a year or more, and some were open for as long as 3 years and across two election cycles. The questions appeared to be an attempt to determine how political the organizations were (which, after all, is the test for (c)(4) status). But some were frankly weird: Whether an officer of the group will run for public office in the future, or what the roles were of audience members in group programs.

In sum, TIGTA found an IRS staff scrambling to keep up with requests for tax-exempt status in an area it did not understand well. The staff seemed unaware of the political implications of what it was doing, and was poorly managed. Senior officials seemed to be aware of the problem as early as 2011, yet could not fix it for a year and a half.

This is a huge embarrassment for the IRS and likely to make it more difficult for the agency to police groups that have stepped over the political line. But based on what we know so far, this is no Watergate scandal.