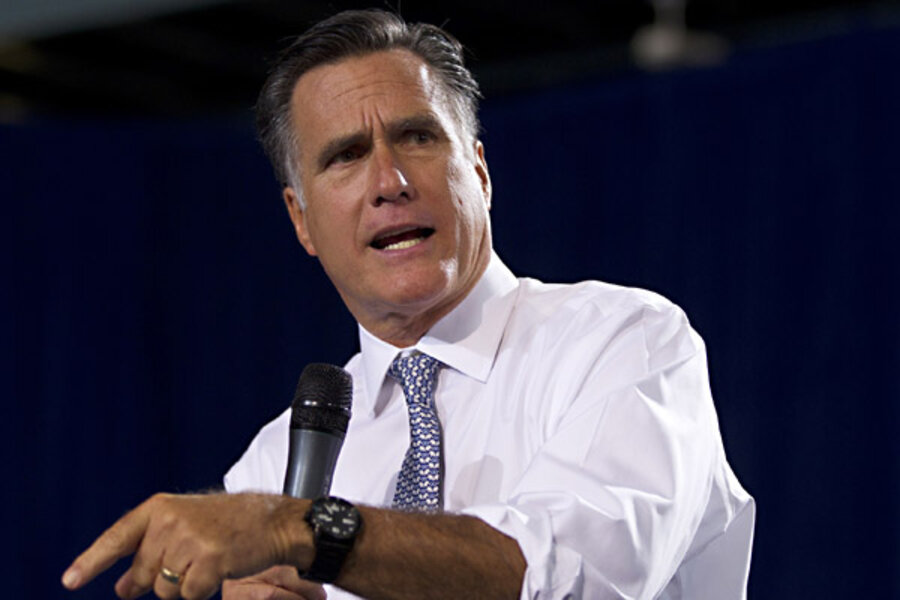

Mitt Romney's tax plan doesn't add up

Loading...

A new paper by Brookings Institution scholars and Tax Policy Center colleagues Bill Gale, Adam Looney, and Samuel Brown is generating lots of media buzz. Even Barack Obama has has put his spin on it with a campaign ad that says if you are middle class, Mitt Romney wants to raise your taxes by up to $2,000 even as he cuts taxes for rich people like himself.

That is a powerful political message, but it isn’t how I read the Gale-Looney-Brown paper. To me, the study highlights something else: The deep contradictions embedded in Romney’s tax platform. Like most candidates, the former Massachusetts governor has made many promises. And like most, he cannot keep them all.

In this case, Romney has promised at least five big things. They are:

- To start, he’d make all of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts permanent but repeal the 2009 Obama tax cuts and the tax increases included in the 2010 health reform law.

- After that, he’d cut tax rates by 20 percent across the board and eliminate both the Alternative Minimum Tax and the estate tax.

- He’d eliminate taxes on investment income for couples making $200,000 or less (individuals making $100,000 or less) and keep current low rates for those with high incomes.

- He’d do this without increasing the budget deficit (beyond the cost of extending the 2001-2003 tax cuts) by curbing some tax preferences.

- He’d do it in a way that retains the progressivity of today’s tax system.

Romney’s problem is he cannot possibly achieve all of these goals. He is doomed by both political reality and simple mathematics.

Romney himself never says how he will make all this happen. Indeed, his tax platform includes a gaping hole. He says he’d finance these rate cuts by broadening the tax base–that is, by reducing some of the tax preferences that litter the Revenue Code. But he never says which of these deductions, credits, or exclusions he’d scale back—or how.

Thus, the real question is not whether Romney is proposing a huge middle-class tax increase (he isn’t). It is which of his ambitious campaign promises he will fail to keep.

That was the exercise that Brown, Gale and Looney engaged in. To show how hard it would be for Romney to achieve all of these goals, they assumed he’d keep his first four promises. If he did, they found it would be impossible for Romney to retain today’s levels of progressivity. Or, to say it another way, if Romney keeps the promises he has explicitly made, the middle class will pay higher taxes and the rich will pay lower taxes.

That’s because cutting rates this deeply without adding to the deficit or raising taxes on capital income would require massive cuts in those popular tax preferences that overwhelmingly benefit the middle- and upper middle-class. Brown, Gale, and Looney figure that tax breaks such as the deductions for mortgage interest and charitable giving or the exclusion for employer sponsored health insurance would have to be cut by as much as 65 percent for Romney’s plan to add up.

While their numbers are slightly different, their basic conclusion is the same as my TPC colleagues Eric Toder, Jim Nunns, Bob Williams, and Hang Nguyen reached in their own paper a couple of weeks ago: You just can’t cut rates this deeply without either adding to the deficit or making steep, exceedingly painful cuts in tax preferences.

Of course, Romney doesn’t have to raise taxes on the middle-class. He could fix this problem with less ambitious rate cuts on ordinary income, or by raising taxes on capital income. He could pay for his initiative outside of the individual income tax system by increasing corporate taxes—though he says he’d cut them. He could cut spending even more deeply than he’s already promised, though that would hurt low- and middle-income households too. Or he could just add to the deficit.

Thus, the right question to ask Romney is not whether he wants to raise taxes on the middle-class. The right question to ask is which of his campaign promises he will abandon.