Opinion: A crisis of public morality, not private morality

Loading...

At a time many Republican presidential candidates and state legislators are furiously focusing on private morality – what people do in their bedrooms, contraception, abortion, gay marriage – America is experiencing a far more significant crisis in public morality.

CEOs of large corporations now earn 300 times the wages of average workers. Insider trading is endemic on Wall Street, where hedge-fund and private-equity moguls are taking home hundreds of millions.

A handful of extraordinarily wealthy people are investing unprecedented sums in the upcoming election, seeking to rig the economy for their benefit even more than it’s already rigged.

Yet the wages of average working people continue to languish as jobs are off-shored or off-loaded onto “independent contractors.”

All this is in sharp contrast to the first three decades after World War II.

Then, the typical CEO earned no more than 40 times what the typical worker earned, and Wall Street was boring.

Then, the wealthy didn’t try to control elections.

And in that era, the wages of most Americans rose.

Profitable firms didn’t lay off their workers. They didn’t replace full-time employees with independent contractors, or bust unions. They gave their workers a significant share of the gains.

Consumers, workers, and the community were considered stakeholders of almost equal entitlement.

We invested in education and highways and social services. We financed all of this with our taxes.

The marginal income tax on the highest income earners never fell below 70 percent. Even the effective rate, after all deductions and tax credits, was still well above 50%.

We had a shared sense of public morality because we knew we were all in it together. We had been through a Great Depression and a terrible war, and we understood our interdependence.

But over time, we forgot.

The change began when Wall Street convinced the Reagan Administration and subsequent administrations to repeal regulations put in place after the crash of 1929 to prevent a repeat of the excesses that had led to the Great Depression.

This, in turn, moved the American economy from stakeholder capitalism to shareholder capitalism, whose sole objective is to maximize shareholder returns.

Shareholder capitalism ushered in an era of excess. In the 1980s it brought junk bond scandals and insider trading.

In the 1990s it brought a speculative binge culminating in the bursting of the dotcom bubble. At the urging of Wall Street, Bill Clinton repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, which had separated investment from commercial banking.

In 2001 and 2002 it produced Enron and the corporate looting scandals, revealing not only the dark side of some of the most admired companies in America but also the complicity of Wall Street, many of whose traders were actively involved.

The Street’s subsequent gambling in derivatives and risky mortgages resulted in the crash of 2008, and a massive taxpayer-financed bailout.

The Dodd-Frank Act attempted to rein in the Street but Wall Street lobbyists have done everything possible to eviscerate it. Republicans haven’t even appropriated sufficient money to enforce it.

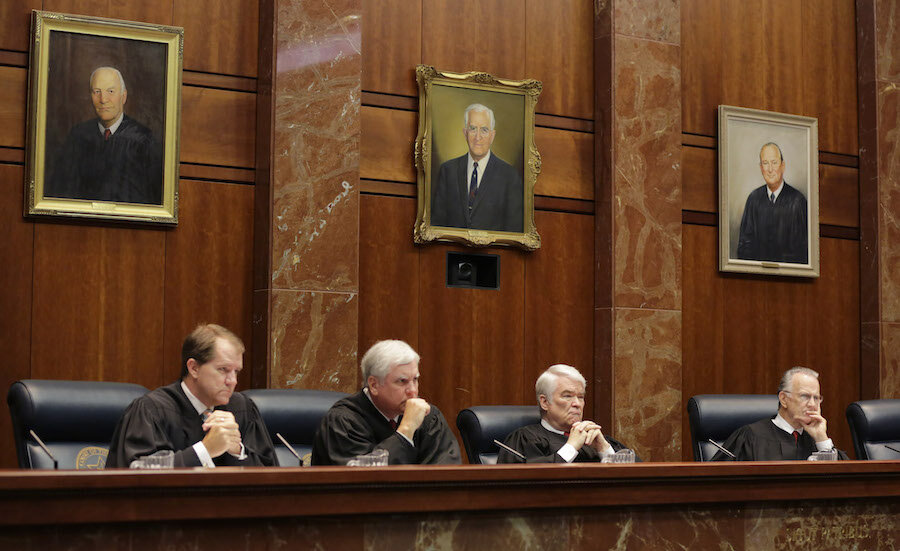

The final blow to public morality came when a majority of the Supreme Court decided corporations and wealthy individuals have a right under the First Amendment to spend whatever they wish on elections.

Public morality can’t be legislated but it can be encouraged.

Glass-Steagall must be resurrected. Big banks have to be broken up.

CEO pay must be bridled. Pay in excess of $1 million shouldn’t be deductible from corporate income taxes. Corporations with high ratios of executive pay to typical workers should face higher tax rates than those with lower ratios.

People earning tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars a year should pay the same 70 percent tax rate top earners paid before 1981.

And we must get big money out of politics – reversing those Supreme Court rulings, providing public financing of elections, and getting full disclosure of the sources of all campaign contributions.

None of this is possible without a broadly based citizen movement to rescue our democracy, take back our economy, and restore a minimal standard of public morality.

America’s problems have nothing to do with what happens bedrooms, or whether women are allowed to end their pregnancies.

Our problems have everything to do with what occurs in boardrooms, and whether corporations and wealthy individuals are allowed to undermine our democracy.