Why two dips in GDP may not mean a recession – yet

Loading...

The U.S. economy in 2022 is not the best of times or the worst of times. It’s sailed instead into a weird patch of ocean, roiled by the deep waters of the pandemic and the gales of war.

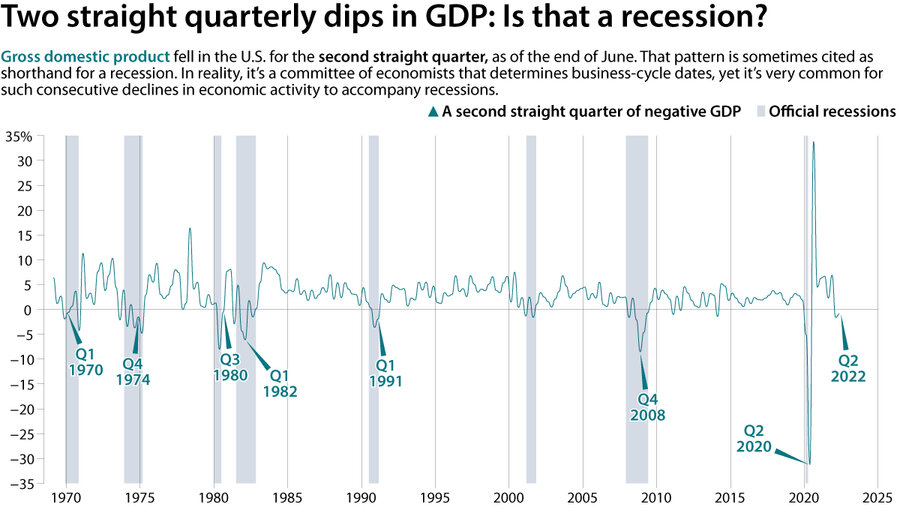

Several telltale signs of economic activity have shifted in recent months and now point to a slowdown. On Thursday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that gross domestic product, a measure of the nation’s output, shrank for the second quarter in a row. In the popular mind, at least, that qualifies as a recession.

But other telltales of the economy look a lot more like the final leg of a strong expansion. Inflation is high; unemployment is near record lows. So perhaps the economic ship isn’t actually in a recession; it’s just starting the turn to head toward one.

Why We Wrote This

Is the United States in a recession? The economy is in an odd in-between space. For many people, it feels like the answer is yes.

The bright side of all this is that even if a recession happens, it’s likely to be a shallow one, many economists say. Even better: Tested by the short but sharp pandemic-driven recession in 2020, many businesses are feeling resilient. The not-so-bright side is that this period might feel like a recession, even if it isn’t one, technically.

“The economy is still growing, but it’s growing so slowly that employment is weak and the unemployment rate is rising and it feels pretty bad,” says Joel Prakken, chief U.S. economist at research firm IHS Markit. He calls it a “growth recession” and says we’re probably already in its early stages.

His firm forecasts barely positive growth for this quarter (0.8%) and much of the same through 2023. (In the first quarter of this year, by contrast, GDP adjusted for inflation fell 1.6% and declined 0.9% in the second quarter, the Commerce Department reported Thursday.)

Recessions are anomalies, interruptions in the currents of increasing prosperity. Since the end of World War II, the United States has been growing more than 85% of the time. Many economists see recessions as unfortunate overreactions at the troughs of business cycles. Edward Leamer, an economist with the UCLA Anderson Forecast, calls them pathologies, which wouldn’t have to happen if the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve, did a better job managing the economy.

A different economic cycle, from energy to housing

One thing everyone can agree on: This particular cycle is especially hard to gauge because of the lingering effects of the pandemic and new uncertainties about energy and food supplies because of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Take energy. Oil prices surged when Russian tanks rolled toward Kyiv. But for the second month in a row, they’ve been falling. Motorists now pay an average $4.28 for a gallon of regular gas, according to AAA, still high compared with a year ago, but lower than the peak of $5.02 in mid-June.

Normally, falling energy prices point to a recession. Ditto for commodities like copper, iron ore, lumber, and cotton, which are also experiencing a price decline. But this time the ups and downs of energy prices have far more to do with shifts in supply than in demand. Much of the West is refusing to buy Russian oil, and it’s taking time for world markets to adjust oil flows to bring the market back into balance.

Housing is another head-scratcher. Sales of new single-family homes, which were rising last year when Americans were desperate to buy before mortgage rates went up, have now fallen to a two-year low. Normally, such declines signal a recession after a period of frenzied activity by lenders and builders. But this time is different.

“We haven’t had the excessive lending and excessive building that’s characteristic of the other expansions,” says Mr. Leamer of Anderson Forecast. “So that makes me think that, if we have a recession, it’s not going to be a very deep one ... because we don’t have the fragile housing market. We need more homes, certainly in California!”

Or consider the car market. Year-over-year sales have been falling for a year, but the problem isn’t demand, which remains strong. It’s supply – a lingering shortage of semiconductors brought on by pandemic-related factory closures.

An unusual labor market, too

Another common telltale is employment. Companies from Peleton and Re/Max to Netflix, Shopify, video-hosting firm Vimeo, and even Tesla have already cut back their workforces. Crunchbase News estimates some 30,000 tech workers have lost their jobs so far this year.

Layoffs normally signal a recession, except in this cycle, the U.S. is still adding jobs overall, not subtracting them. The unemployment rate is near lows not seen since 1969. And for every worker available to take a new job, there are 1.9 positions open, according to the latest government data – also near record highs.

Such strong job growth typically signals the late stages of an expansion. But this time the labor shortage is due, at least in part, to the reluctance of many workers to return to work after the pandemic. The pandemic has interfered so much with employment that Mr. Leamer has for now dropped it as an indicator for forecasting recession.

Tight labor markets also play a role in inflation. If energy and commodity prices continue to fall, then the key to future inflation will be what kind of pay raises workers demand. In a recent survey of small businesses, nearly half were planning to take out a line of credit this year. Of those, a quarter were preparing to use the debt to raise existing employee salaries, according to Kabbage, an American Express data and technology company offering funding for small business.

Tough moment for the Fed

In the 1970s and early ’80s, the only way the Federal Reserve found to crush inflation was to trigger a recession. That caused unemployment to go up and tempered workers’ wage demands. With inflation again approaching those double-digit levels, the central bank on Wednesday hiked short-term interest rates by three-quarters of a percentage point, after an identical hefty increase in June.

All the Fed has to do this time is raise unemployment by about half a percentage point from today’s low 3.6% rate, says Mr. Prakken of IHS Markit. That would do very little damage to the economy and achieve what economists call a “soft landing,” he adds. “But here’s the rub. Even if it only will take an increase in the unemployment rate back up to 4.1% to quell inflation, the historical experience since World War II is that the unemployment rate has never risen by just that amount without actually rising a lot more than that and slipping into recession.”

There’s plenty of skepticism the Fed can engineer a soft landing. In a new study, Mr. Leamer found that the best predictor of recession is the yield curve – the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates. When the Fed boosts short-term rates and banks won’t offer investors a higher rate for holding their money for longer periods of time, it’s a sign that lenders are skittish about the future. He says it’s not clear the Fed is overly worried about such curve “flattening.”

Slightly more than half of consumers believe the U.S. is already in a recession, according to a NielsenIQ report last month. In a new Kabbage survey released this month, more than 4 in 5 small businesses worried about a potential U.S. economic recession.

At the same time, 80% of the firms said they were confident they could withstand it. Their top reason for optimism? The pandemic. “It helped them find a greater sense of resilience and preparedness to be successful in the future despite economic turbulence,” writes Brett Sussman, Kabbage’s chief marketing officer, in an email.