Where’s the beef? Pandemic exposes cracks in US food system.

Loading...

Business is booming at Codman Community Farms in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, sales of pasture-raised meat and eggs have been up some 500%, says Jennifer Hashley, who lives on the farm and directs a farming sustainability organization affiliated with Tufts University. It’s hard to keep the farm store stocked. People who have never bought locally are buying out eggs and lamb and lettuce.

“People are coming out of the woodwork to purchase directly from us,” she says.

The situation is quite different for the farmers Dermot Hayes contacts regularly in his role as professor in agriculture and life sciences at Iowa State University. There, facing a dramatic slowdown in processing plants, hog farmers have been making the excruciating decision of whether to slaughter and discard tens of thousands of piglets – next month’s food – or to dispose of fully grown pigs who should have been going to grocery stores. Either way, the economic and emotional impact is devastating.

Why We Wrote This

Despite shortages, many food watchers have been impressed with just how well the U.S. food supply has held up in crisis. Still, the pandemic has exposed shortcomings in a complex and often convoluted food system.

“It’s truly awful,” Mr. Hayes says. “I’ve been on calls with them, and there are people crying on the phone.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Across the country, the pandemic has rippled through the food chain and agricultural sector, often in divergent ways. Americans are facing shortages of some staple foods, such as flour and dried beans. Price fluctuations, such as the dramatic spike in the cost of eggs last month, have fueled cycles of panic buying. Images of empty supermarket shelves and farmers plowing under crops have gone viral across social media. Farmers, meanwhile, are facing unprecedented financial challenges, even as some direct-to-consumer operations are flourishing.

Throughout this, many agricultural economists point out, overall access to food for Americans has remained remarkably stable. But the challenges and changes have been unnerving to many. And this has led some to take a closer look at the country’s food supply chain – perhaps for the first time – and wonder whether there are ways it could be improved.

“It’s incredible to think about how this system works,” says Trey Malone, an assistant professor and extension economist with Michigan State University’s department of agricultural, food, and resource economics. “Less than 1% of the American population works in agricultural production. All of us rely on this system. And 99% of us don’t think about it. This is one moment where you think, ‘Oh my goodness, I don’t know where this food has come from.’”

Cracks emerge

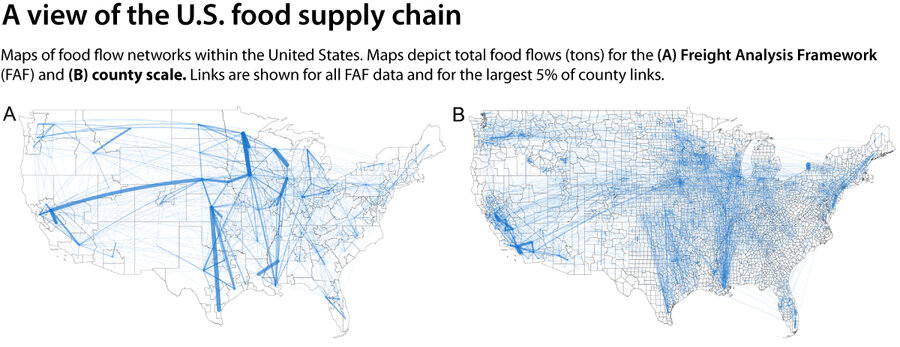

The food supply chain in the United States looks more like a massive spider web than a line. A research team at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign last year used multiple data sources to produce a map showing the flow of grains, fruits and vegetables, animal feed, and processed food items within the country. They found 9.5 million or so points of contact between different U.S. counties. A farmer might grow corn in one location, for instance, ship it to another state for storage, have it transformed into animal feed in a different county, then shipped elsewhere to a feedlot. The animals who eat that feed might be processed in yet another location, and then returned, shrink-wrapped, to grocery stores near the farm where the corn was first harvested.

Look globally, and the situation gets even more complicated. The U.S. imports about 15% of its food, including just over half of its fruits and vegetables, and most of the coffee. It exports, in dollar terms, a bit more.

For the most part, this has created a system of plentiful and accessible food. But during this pandemic, some nodes of this supply web have turned into choke points, often because of policy decisions unrelated to agriculture.

When airlines, for instance, grounded flights, that also meant a slowdown in trade, explains Will Martin, a senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute.

“Half of the world’s air freight goes in the bellies of passenger planes,” he says.

When restaurants and schools closed to comply with social distancing orders, markets disappeared for farmers and processors. There are separate chains for the residential market and the “food away from home” market. And although the latter tends to be hyper efficient – producers can predict, for instance, how many wings American consumers will eat at restaurants during March Madness – it is also quite difficult to pivot. (When March Madness is canceled, the production chain can’t just shift to turn that chicken into boneless breasts sold at grocery stores.)

“It’s a totally different business model,” says Kathleen Finlay, president of the Glynwood Center for Food and Farming in Hudson, New York. “If you are a wholesale farmer, you’re growing a few crops and you’re selling a lot of it to a relatively small number of buyers. You don’t have ads. You don’t have a website. You don’t have a way for a person to buy food from you. ... It’s a totally different back end and production plan.”

Think about eggs, says Jayson Lusk, head of the agricultural economics department at Purdue University. Some big egg operations only supply restaurants. Others produce only 50-gallon drums of liquid eggs to be used in cafeterias. These operations don’t have people to grade the eggs or put them in cartons for consumer retail. They can’t even get cartons because cardboard manufacturers can’t switch up their operations to make the correct packaging quickly enough. Add to that a rush of consumers baking at home and there is a temporary shortage.

“Everybody shows up in the grocery store buying eggs,” he says. “The industry wasn’t able to adapt to that.”

Finding flexibility

Glynwood and other groups, including Ms. Hashley’s New Entry Sustainable Farming Project, which guides newcomers to the agricultural sector, have been working with local farmers to figure out how to market directly to consumers. While they don’t suggest eliminating imports, either from across the world or across the country, they believe that establishing more robust local networks will lead to a more resilient system.

“The conventional food system that is homogeneous and centralized has vulnerabilities in lots of ways,” Ms. Finlay says. “We’re seeing it right now in meat production and processors.”

Last month, some of the country’s largest meat processing plants, which control most of the meat going into the country’s food system, stopped operation because of concerns about their workforce and COVID-19. That created not only a shortage of meat throughout the country, but what Professor Hayes describes as an “elevator effect” for hogs coming through the system. With farmers unable to ship their fully grown pigs to the processors, there was no room in their barns for the piglets that they had already contracted months ago to purchase. And so the animals piled up.

With such a small number of processors handling such a large percentage of the meat coming through the system, the impact was devastating, says Professor Hayes. Agricultural groups are working with the federal government to help get assistance to livestock farmers, and also ease regulations on smaller producers and processors so that ranchers and farmers can more easily sell directly to consumers.

But longer term, many experts say, there may have to be a debate about whether to bring more automation into animal processing, whether to create less efficient but more flexible processes for production, and how to mitigate the pandemic’s financial toll on farmers so that agricultural production doesn’t drop.

“We need to think long and hard about how we support our growers in the United States,” says Professor Malone.

Throughout all of this, Professor Lusk says, it will be important to keep in mind how well the American food system has done – despite the inability to find those dried chickpeas.

“I think the food system responded remarkably well to this totally unexpected, really abrupt change,” he says. “There’s food. People say, ‘Well, I had to do without my favorite brand a few days.’ It just shows how much we take for granted.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.