Government check in the mail? No, on a debit card.

Loading...

When Crusberto Muñoz opened his unemployment benefits letter early in January, he didn't find a check. What popped out instead was a Visa debit card loaded with $116.

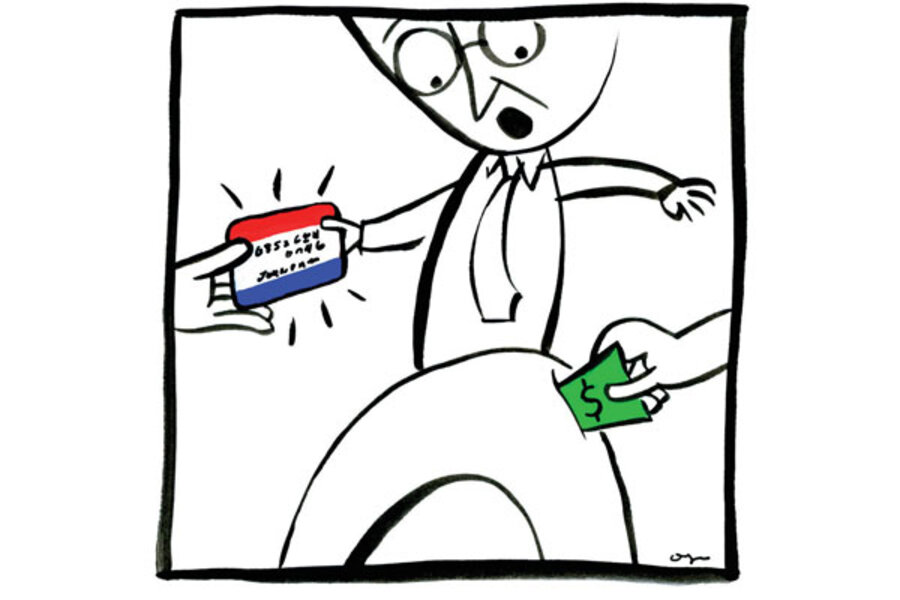

The Muñozes were perplexed. When his Pendleton, Ore., firm laid him off temporarily last year, Mr. Muñoz had gotten his unemployment deposited directly into his bank account. Why the card this time? Virginia Muñoz read and reread the letter. She found that the debit card, issued by U.S. Bank, came with fees: $1.50 for using an ATM outside U.S. Bank's network, a fee for making more than two withdrawals a month, and most galling of all, a provision to opt in for overdraft protection that, if used, would cost $17.

"The Federal Reserve called the banks' use of the overdraft fees 'abusive,' " she writes in an e-mail. "But for some reason, the government has decided that it's not 'abusive' for unemployed people to have overdraft coverage." The Muñozes ignored the card and applied for direct deposit.

That small act of defiance comes in the face of a blizzard of government-sponsored plastic. For years, states, along with Uncle Sam, have been urging recipients of government aid to accept electronic payments because they're cheaper than paper checks. For most people, that meant direct deposit into a bank account. But the holdouts who didn't want it or didn't have an account still got checks. Then governments found a substitute: debit cards, which they began sending to holdouts – from foster parents to state prisoners. By 2009, 30 states already had deals in place to replace unemployment checks with debit cards, according to The Associated Press. They were joined by South Carolina and California last year. In December, the US Treasury Department said it would phase out paper checks for new Social Security applicants starting in May. Earlier this month, it announced it was testing a similar move for income tax refunds.

While the cards have great appeal – the money comes faster and there are no hassles with lost or stolen checks – they have also generated controversy. Some recipients complain it is unfair for the government to offer benefits to the neediest Americans with one hand and then take some of it back through fees. Another concern: Does government money in the form of a debit card encourage undue spending?

"It is safer than cash and the fees are lower than check-cashing operations, which means you can keep more of your money," said Bill Hardekopf, chief executive officer of credit-card website LowCards.com, in a statement. But "studies show that people tend to spend more freely with a debit card than paying with cash."

The move to government electronic payments is global. Of 40 social-transfer programs launched by nations in the past decade, nearly half featured electronic delivery, according to a 2009 report by Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, an independent policy and research center in Washington, D.C. Such moves are largely popular because ATMs, where electronic payments can be turned into cash, are more accessible than a bank or a government office. In the United States, the big driver is costs.

Electronic payments are cheaper than printing out and mailing checks. Nebraska figures it saves 60 cents for every check it eliminates. For the US government, it's about 90 cents.

Moving 11 million Social Security recipients to debit cards is expected to save $1 billion over the next decade. The move to plastic also saves money for recipients who otherwise pay $6 to $26 at costly check-cashing outlets, says Dick Gregg, fiscal assistant secretary at the US Treasury.

Government-sponsored debit cards also tend to have fewer fees than those sold in stores. For example, Treasury's Direct Express MasterCard, issued to Social Security recipients, "is infinitely better than any debit card," says Tim Chen, CEO of NerdWallet, a credit-card search website. There's no monthly fee, no charge to use it at a store and get extra cash back or to make an ATM withdrawal per month. By contrast, one of the most popular and lowest-cost prepaid cards from the private sector – the Walmart MoneyCard – charges $3 as a monthly maintenance fee, $2 to withdraw cash at an ATM or a bank teller, and $1 even to find out the balance at an ATM.

Governments have such a big customer base and regular cash flow that they can usually negotiate low fees with debit-card issuers. It gets trickier when the cash comes only once a year, as in tax refunds, says Josh Wright, Treasury's director of financial access innovations. That is why one of Treasury's pilot programs for tax refunds will test whether recipients will accept a $4.95 monthly fee.

Direct deposit into a bank account is still the better deal for most Americans, says Mr. Chen of NerdWallet. But with an estimated 7.7 percent of Americans households without a bank account, advocates for these "unbanked" Americans welcome Treasury's experiments with debit cards. It will give them more financial options.

For example: The tax-refund card – called the MyAccountCard Visa – will be able to hold wages and bank transfers as well. Some versions will have a savings feature. "The pilot is an excellent start to bringing low cost transaction and savings products to millions of tax filers," said Melissa Koide, of the Washington-based Center for Financial Services Innovation, in a statement.

The cards will force recipients to learn new ways of handling money. "Before, you had $100 in your pocket," making it easy to track how much you had, says Paul Gada, personal financial planning director for the Allsup Disability Life Planning Center, a Belleville, Ill., firm that helps people sign up for Social Security disability and Medicare benefits. "With the card, you can still find your balance, but again there's this extra step [of using an ATM]. And the financial planners tell you to get rid of that step."

Also the card fees that remain, such as making too many withdrawals or using an out-of-network ATM, keep people like Mrs. Muñoz skeptical.

Still, she's had to compromise. When bills came, the couple activated the card. "I would like to say that we stood our ground and refused to deal with the U.S. Bank big-fee card," she says. "But unfortunately, the $116 is too much for us to pass up."