Foreclosed homes: three potential fixes for the crisis

Loading...

Four years after the housing market peaked, the foreclosure crisis keeps rolling on.

Six million borrowers could lose their foreclosed homes to the bank in the next two years, by some estimates. Other Americans are feeling the ripple effects in sagging home prices. And the problem persists despite numerous policies crafted to address it.

A new twist in this drama: Concerns raised about poor-quality legal documents have caused a sudden freeze in foreclosure proceedings by some lenders. Politicians have begun calling for all foreclosures to cease while the issue is being investigated. The upshot may be confusion and delays, but it won't end the foreclosure wave, which is driven by high unemployment and declines in home values.

Does more need to be done, and if so, what?

For the Obama administration and whoever controls Congress, that is a prime question.

Some housing experts are calling for significant new programs to help borrowers, but few see a quick or simple fix.

"I don't think the housing market is going to get any better until the labor market starts improving," says Patrick Newport, a housing economist at IHS Global Insight in Lexington, Mass. "Everything hinges on the labor market." (See story on job creation, page 32.)

In a way, America's record tide of foreclosures is just the most troubling symptom of the real problem: too much mortgage debt.

"At the top of the bubble,... we created a whole lot of debt relative to the value of houses that seemed to be there," says Alex Pollock, a finance expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

Then home values fell, but much of the debt load remains on household balance sheets.

The solution involves some sort of adjustment, Mr. Pollock says, whether through default or some conversion of the debt into a new, affordable structure.

Here's a closer look at some of the main options for housing policy: an all-out approach to loan refinancing, intermediate refinancing efforts, and the status quo.

1. Create an all-out refinancing effort.

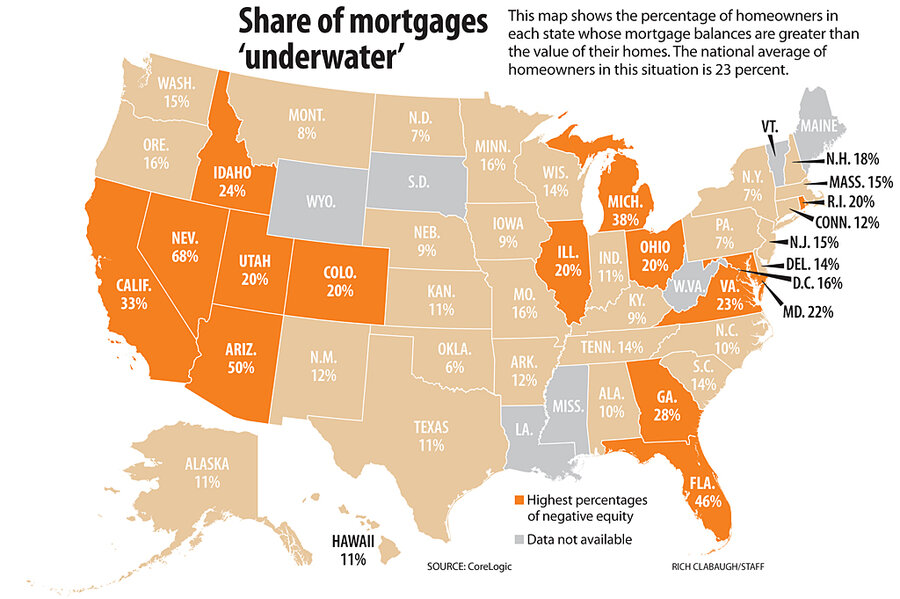

One approach, advocated by economists Glenn Hubbard and Chris Mayer, would be to offer a simple refinance for most US borrowers at today's ultralow mortgage rate (just over 4 percent). Currently, that's not available to "underwater" borrowers, whose home values have fallen lower than their loan balance (also known as negative equity). Under this approach, the low fixed rate would be available to anyone with a loan backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or the Federal Housing Administration (FHA).

The result would put cash in the pockets of millions of borrowers – quickly and for years to come. That could boost consumer spending and reduce the likelihood of default.

One problem: Borrowers with negative equity would still be underwater. Thus they might be prone to default if they want to sell the home but can't pay off the loan.

Another approach is a refinancing program that focuses on writing down principal balances on millions of loans, forgiving enough to create positive equity. Since lenders have been reluctant to do this, a new federal effort could subsidize the lender write-downs – and perhaps recoup some of the taxpayer expense by having the government share in any price appreciation that's realized when the home is sold.

The big argument for these approaches is to try to prevent home prices from taking an additional plunge due to foreclosures. The idea is to disrupt a self-reinforcing spiral, where falling prices push more borrowers underwater, leading to more defaults, more homes for sale, more people with tarnished credit scores, and so on.

The aggressive plans have problems, though. Taxpayers aren't in the mood for more bailouts, and these efforts would put taxpayer dollars at risk.

2. Push lenders to forgive principal.

It's in lenders' interest, many economists say, to write down loan balances so that fewer borrowers default. (Currently, 1 in 4 home sales involves a distressed property, and banks incur heavy costs to foreclose and sell at a loss.) The trick, they argue, is to nudge creditors to do "the right thing" for themselves as well as the economy.

The Obama administration's Home Affordable Modification Program already has some of this, in part via a "short refinance" option, in which the current lenders take a principal loss to enable an FHA refinance. But overall, the volume of loan-balance write-downs has been tepid.

One sticking point is a mismatch in incentives, says economist John Geanakoplos of Yale University in New Haven, Conn. Investors collectively "own" mortgages in bundled securities, and write-downs are arranged by loan-servicing firms with conflicting interests. His solution: Require a government trustee to determine the fate of at-risk loans, choosing foreclosure or write-downs based on the best interest of investors.

The agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also own a lot of loans, and Laurie Goodman, mortgage strategist at Amherst Securities in New York, urges legislation authorizing them to forgive more principal. Others focus on bank-held loans, arguing that regulators could prod banks to do write-downs.

The downside: Plenty of foreclosures would probably still occur, and getting new programs up and running isn't easy.

3. Do nothing more; let the market correct itself from here.

This option may not be pretty, but it's a time-honored way of working through credit problems, proponents of this approach say.

With a modest economic recovery, further declines in home prices should be modest, they predict. The downward pressure of distressed properties would be offset by an improving job market.

David Olson, a real estate consultant with Access Mortgage Research in Columbia, Md., offers another reason: Banks are swamped just trying to adapt to already-enacted housing policies and regulations (the massive financial-reform law). "They can't deal with all the change," he says. "There's a lot to be said for just letting the market adjust."

The main risk in this approach would be if the housing crisis deepens and helps push the economy back into recession. Still, current housing policies should "pretty much be enough to get us by," says Celia Chen, a housing economist at Moody's Analytics in West Chester, Pa.

The freeze in foreclosures, if it lasts, only delays the reckoning and adds to uncertainty, she says. The longer that disputes over the foreclosure process go on, "the more uncertainty there is."

In addition to delaying many foreclosure transactions currently in process, the controversy over foreclosure paperwork at some of the largest banks could potentially expand into an even bigger problem for the industry.

The team of analysts led by Ms. Goodman says the controversy could lead to broader foreclosure moratoriums (affecting more lenders), to a reexamination of the title-transfer process, or to litigation regarding homes that have already been foreclosed on and sold.