World debt crisis: eight reasons you should care

Loading...

| Boston

It's a sign of the fragility of the world economy that the debt problems of Greece, a nation the size of Ohio, can throw global markets into turmoil, cause a run on one of the world's premier currencies, and call into question the viability of the European Union.

That's not all. Some see the tremors emanating from Athens as the precursor to a debt earthquake that could engulf much of the developed world.

If Greece today, who will it be tomorrow? Bond markets have already begun to speculate: debt-laden Portugal? Slow-growing Spain? It's possible the crisis will jump to Britain, Japan, or even to the United States.

The implications of a debt crisis spreading beyond Europe have already rattled stock markets. Here are eight reasons you should be paying attention, too:

1. Because it will impact your neighborhood tool-and-die maker.

The financial crisis has caused the value of the euro to plummet, making it harder for the US and other nations to boost their economies through exports.

As the world's largest trading bloc, the European Union (EU) represents 7 percent of the world's consumers but a fifth of world trade. The dramatic fall in the value of its currency thus has major implications.

If the euro doesn't recover, exports to Europe will fall because they'll be more expensive relative to goods already made in Europe. Similarly, the US, China, and other nations may find it more difficult to export in general, since competition would intensify with European companies, whose goods and services have suddenly become cheaper.

That doesn't automatically mean Europe's slowdown will undercut America's economic rebound. "Problems in Europe could dent our recovery, but not abort it," says Barry Eichengreen, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.

2. Because it could affect things at the bank window – again.

If one or more of the highly indebted nations defaults, it may well trigger another banking crisis, not just in Europe but worldwide.

France holds nearly a third of Greece's debt, a fifth of Spain's, and a sixth of Portugal's. Germany holds a smaller share of Greece's debt but similar proportions of the debt of the other two. Should one of these nations default, European banks would be hit hard, raising questions about their ability to survive. (See chart, page 29.)

In 2008, concerns about the viability of US banks brought the financial system to the brink of collapse. "You've got the ingredients for a major banking crisis," says Rob Parenteau, who edits the Richebächer Letter, a weekly and monthly financial newsletter, from his base in Berkeley, Calif.

3. because your portfolio will rise and fall like the bay of fundy.

The stock market, which abhors uncertainty, now has a fiscal crisis that could weigh on global investor psychology for months, if not years.

Investors have already had a foretaste of what euro worries alone can to do US stocks. After hitting a 19-month high on April 26, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged more than 7 percent in two weeks, regained 5 percent the following week, then fell again as the euro reached new multiyear lows against the dollar. Expect more volatility as asset bubbles and other imbalances in national and company ledgers emerge – and not just in Europe.

"These are all manifestations of the same core problem: massive debt that can't be repaid," says George Feiger, chief executive of Contango Capital Advisors, a wealth management firm based in San Francisco. "We will shuffle it around and disguise it. But it keeps popping up."

What nations have to figure out is who will pay down the debt: Will homeowners and taxpayers shoulder the burden? Or will banks, hedge funds, and other creditors write down – in effect, forgive – part of the red ink?

The challenge is that every write-down involves a loss for somebody, perhaps a big investor or a retiree dependent on a pension fund, Mr. Feiger adds. This is to say nothing about what a collapse of the euro would mean. The global loss of wealth, one way or the other, could be huge. Keep the phone number of your investment adviser near by.

4. Because it could affect how the world deals with that mercurial North Koreanfellow, Kim Jong-Il.

The debt problems are pushing the nations of the European Union into an existential crisis that will divert them from solving other pressing challenges.

At the root of the matter is the question of whether EU nations should bind even closer together, accept some kind of EU mechanism for fiscal discipline, and give up some sovereign authority. The alternative is a breakup of the EU's 16-member monetary alliance.

The current middle ground looks untenable as voters in fiscally prudent nations, especially Germany, ask why they should finance the excesses of Greece and others if there's no way to force them to change their ways. The potential for an EU or eurozone breakup has ramifications far beyond the economies involved.

"The Europeans are our valued allies," says Professor Eichengreen. "If they are feuding among themselves ... it's harder for them to work with us on problems like North Korea and Iran."

5. Because if it happens to them, it can happen to us.

The European crisis is a warning for the US and the world's other highly indebted advanced economies that they will share the same fate if they don't get their fiscal houses in order.

For all sorts of reasons, the US is not Greece. It has a more productive economy, its own strong currency, a more robust tax-collection system, and a fairly transparent budget process that shouldn't produce the kind of dramatic deficit revisions that sparked the Greek debt crisis. But what the US does have in common with Greece is too many unbalanced balance sheets.

Both countries are running big deficits. Both have reached levels of indebtedness where, historically, it has proved difficult for nations to grow their way out of trouble. The reason? High debts slow growth.

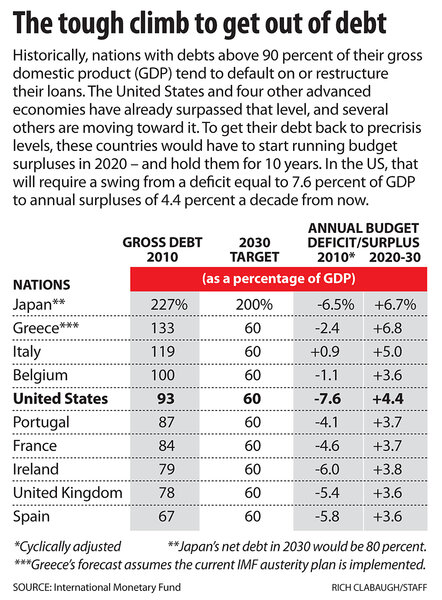

Over the past 200 years, advanced nations whose debts equal 90 percent or more of their gross domestic product have seen their growth rates halved, on average, from 3.4 percent to 1.7 percent, according to a study by economists Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University. That's a huge slowdown. It suggests that if the debt crisis spreads to advanced economies beyond Europe it will take years – possibly decades – of growth to cure the problem.

"Debt crises are not the kinds of things you can get rid of quickly," says Professor Reinhart. "You have a very overvalued currency, and currency markets can deal with it quickly. But you don't make debts disappear."

As a group, the world's advanced economies reached the 90 percent debt-to-GDP tipping point at the end of last year, according to a new report from the International Monetary Fund. Greece's ratio stands at 133 percent; Japan's is at an untenable 227 percent; the US, 92 percent; and the United Kingdom, 78 percent.

It is tempting – and wrong – to blame the rise in debt levels on the stimulus spending of governments. Recession caused two-thirds of the debt surge in the advanced nations known as the Group of 20 (G-20), according to the IMF. Recession shrank the size of their economies (and hence their GDP), making the debt look worse. It also curtailed government revenues, adding to the deficits. The G-20 stimulus packages, by contrast, only account for about a tenth of the rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

6. Because no easy solutions to the crisis exist that won't affect jobs and possibly mortgage rates.

Greece has taken the austerity route to solving a national debt crisis and, by many accounts, it illustrates precisely what not to do. Although Prime Minister George Papandreou's push to cut the country's deficit from 12.7 percent of GDP to 2.8 percent in three years is politically courageous, it's so austere that it looks unlikely to prevail with the rebellion-minded Greek people. Even if it succeeds, the economy would endure years of recession.

Ireland represents another prototype. In its second year of severe budget cuts, including health-care services and public-worker salaries, Ireland still finds itself with the largest budget deficit in the eurozone, above 14 percent of GDP. Meanwhile, its economy has shrunk by almost 17 percent, unemployment stands at 13.4 percent, and property prices have fallen by a third.

Many experts agree that economic growth is crucial to surmounting a debt crisis. The only reason that Greece is going the austerity route is that it has run out of time and good alternatives. It can't inflate its currency, which is another standard solution to dealing with a debt crisis because it makes exports more competitive and brings in more tax revenue through higher prices. But Greece doesn't have a currency to inflate. It uses the euro.

A third approach, simply defaulting on its loans, or restructuring them, doesn't seem to be an option either. The EU appears unwilling to let that happen, for understandable reasons: It doesn't want a bankrupt nation in Europe, particularly when so many members of the EU have so many ties to one another's finances.

Yet many experts think some sort of loan restructuring is inevitable at some point. On May 17, Mr. Papandreou acknowledged his austerity program would only work if the country could get loans to stimulate growth, which means some country giving Athens more money at an affordable rate.

What this crisis does more than anything is provide a warning – a kind of Greek chorus – for other nations. Bond traders' doubts about Greece, which pushed up its borrowing rates and precipitated the crisis, have already spread to Portugal, Spain, and to some extent Italy and the United Kingdom. Similar credit worries could imperil the US financial system, but no one knows if they will for sure, or when.

"In Southern Europe there is no time left, and in the UK there is no time left," Eichengreen says. "In the US we still have some time. [But] we could wake up in three or four or five years and find ourselves in the same position."

7. Because the U.S. approach to the problem may increase your tax bill and lower your Social Security check.

As the US considers ways to reduce the national debt, the most common – but not necessarily politically acceptable – solution is to cut spending and raise taxes. The speed with which this can be carried out depends, to a great extent, on the economic recovery.

Under the most optimistic scenario, the US continues its sharper-than-expected rebound, despite the deepening gloom in Europe. This gives Congress and the White House time to forge compromises that allow the federal government to raise taxes and cut spending and future entitlements.

Even then, it is difficult to envision a way to get back to a precrisis debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 percent. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) calculates that the US government will have to swing from a (cyclically adjusted) deficit of 7.6 percent this year to a 4.4 budget surplus in 2020. Then, those budget surpluses would have to last another decade. That's a huge swing of 12 percentage points in the budget, which represents hundreds of billions of dollars. It's a bigger turnaround than even Greece still has to make beyond its current austerity plan (see chart at right).

Another scenario, let's call it the muddle-through approach, envisions more moderate growth and a failure of policymakers to do anything until some event – say, a run on the dollar or a default by a major country – brings home the seriousness of the debt problem. Then Congress begins cutting spending and raising taxes. Expect some inflation, too.

"You have to be smart about it," says Donald Marron, director of the Tax Policy Center in Washington and former member of President Bush's Council of Economic Advisers. One classic way to cut spending – increasing the eligibility age for Medicare and Social Security – doesn't have an immediate payoff but offers long-term benefits by keeping people employed longer. On the revenue side, he advocates tax simplification, which would eliminate loopholes and make the tax-collection more efficient.

Most of the time, policymakers push through tax increases in combination with sweeteners for voters, Mr. Marron says. "This is mostly going to be a spinach course."

The gloomy scenario is that market jitters about the European debt crisis spread quickly to the US before a recovery can gain much traction.

"There is a contagion effect," says Mr. Parenteau, editor of the Richebächer Letter. Hedge funds, pensions, and professional investors, driven by the lure of profits, will bet against highly indebted European nations, one by one, driving up their borrowing costs until they pass credible austerity packages. "They've done Ireland already and Greece," he says. "When they're done picking the UK clean, they're coming over here. And once they're done with us, they'll probably go to Japan."

The investor wolf pack, as he calls it, has to be resisted. Instead of cutting spending and raising taxes, he argues that governments should push pro-growth, full-employment policies. "If there's ever a time when you run a fiscal deficit, it's when you go into a deep recession.... No wonder the fiscal deficits blow out to 10 to 12 percent. That's what they're supposed to do" in times of recession.

If that means running up [budget] deficits to 17 percent of GDP, in a worst-case scenario, so be it, he says. "Instead of saluting to this religion of fiscal rectitude, they should go for growth."

Maybe so. But history doesn't necessarily validate that strategy: Over the past 200 years, periods of high debt have rarely been accompanied by periods of high growth, meaning it's difficult to grow your way out of a massive overdraft.

8. Because you'll be able to say 'i told you so.'

OK, this isn't a valid reason to pay attention to the world debt crisis. But it might make you feel good, or at least be a know-it-all at the monthly book club.

The fact is, all that has unfolded this decade – the housing bubble, the banking crisis, the stock market plunge, and now the prospect of governments defaulting on their debt – has happened before, over and over, in nations around the world. It has been a predictable narrative for more than 200 years, according to Reinhart's research.

During debt bubbles of the past, analysts and policymakers have always explained why this time was different: The system is stronger or the markets are smarter or the regulations are better. Each time, the bubble has burst and governments and consumers have had to relearn the dangers of too much debt.

If there is something different this time, it is the scale – how the debt crisis engulfs so many nations at once, Reinhart says. And they are the advanced economies rather than the emerging ones. The last time that happened was during the Great Depression.

"What began in the summer of 2007 is nothing less than a world crisis," she says. "We have been through a very tough part, but we still have tough times ahead.... There's no pretty way out."

The best thing you can do, experts say, is to address the problem early, before it becomes too acute. In the mid-1990s, Canada was facing big deficits and a yawning national debt. Scared by the Mexican peso crisis, it took dramatic steps to reduce the red ink, and today its economy looks relatively strong.

The lesson, in other words, is to avoid complacency. "What worries me always," says Reinhart "is that there is still this smug view that those things happen in Greece, but they can't happen here."

Related: