Unemployed for six months or more – and still looking for a job

Loading...

| New York

Over the past two years and four months, Denise Sims-Bowles has sent out 273 résumés – each of them tracked on a spreadsheet on her computer.

But the resident of Pasadena, Calif., who has more than 20 years of work experience, has yet to land a position in the soft Los Angeles job market.

"It's not that I don't have skills," says Ms. Sims-Bowles, whose job entailed taking everyday tasks and automating them. "I look for a job every day, and every day I have the door slammed – hard. To be honest, it's hard to remain positive."

Sims-Bowles is one of the long-term unemployed, a group that has been growing every month since at least late 2007. These individuals have been out of work so long that it's hard for them to explain to potential employers why they are still pounding the pavement. Many have exhausted their connections, and, like Sims-Bowles, they're getting doors slammed in their faces.

Many of them have resigned themselves to jobs with lower pay and responsibilities – or they've dropped out of the workforce entirely because they are convinced there is no job for them.

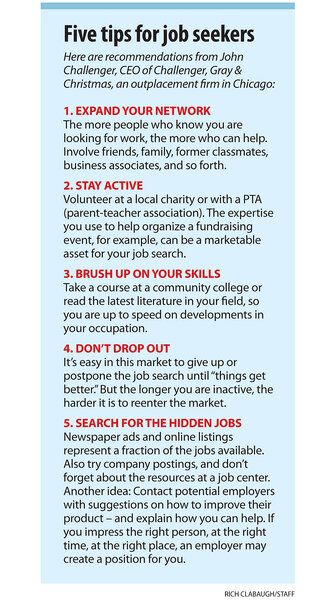

"It's one of the riskiest byproducts of this recession – that we may have a segment of the workforce who may feel so disconnected and forgotten that they feel like there is nothing out there for them," says John Challenger, chief executive officer of Challenger, Gray & Christmas, an outplacement firm in Chicago. "These are productive people who have been put into some kind of space where they are outside in the cold and cannot get back in."

In December, 6.1 million people – some 40 percent of the people who were unemployed – had been out of work for six months or longer, the Department of Labor reports. This represents the largest pool of the long-term unemployed since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started keeping track in 1948.

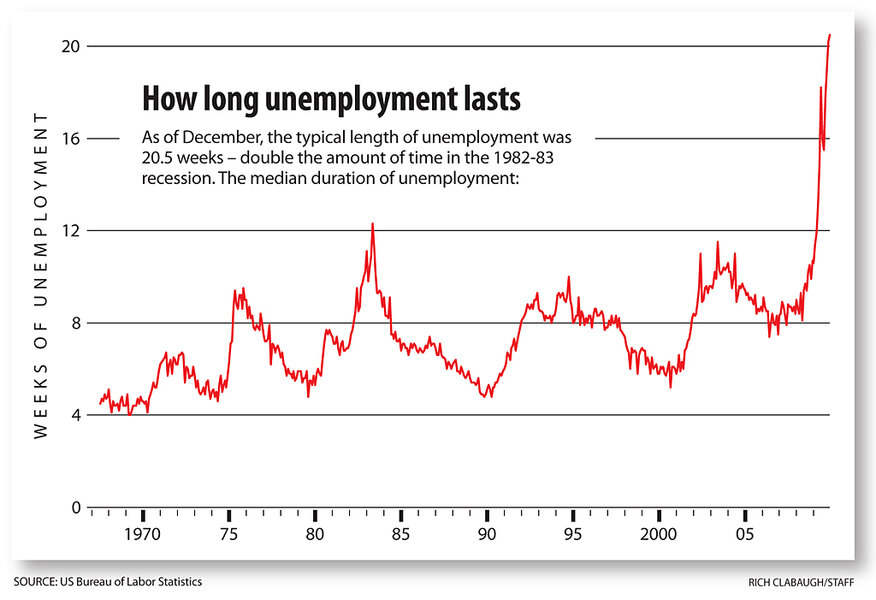

On a median basis, the typical duration of unemployment is 20.5 weeks – double the amount of time in the 1982-83 recession.

The ripple effect

Long-term unemployment has broader ramifications for the economy. For one thing, consumers are concerned that if they lose their jobs, they'll be unemployed for a long time. Such concerns have led to relatively weak readings for consumer confidence, says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Economy.com. Weak confidence means that consumers spend less money – not a good thing for a consumer-driven economy.

In addition, long-term unemployment is an indicator that permanent, structural changes have taken place in the economy. Structural changes can make it much harder for the economy to recover – and for job seekers to adjust.

"Longer term, one of the impacts of structural unemployment is that many of these workers are losing skills, which makes them much less marketable and makes it much tougher to get back," Mr. Zandi says.

Yet compared with the Great Depression, today's unemployment problem seems mild. By the winter of 1933, an estimated 12 million to 14 million people, or 25 percent of the workforce, were unemployed. Six years later, the unemployment rate was estimated at 17 percent.

"My sense is that most people were unemployed for the long term," says David Kyvig, distinguished research professor at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb and an expert on the Depression. "Everyone was desperate to hold on to a job, so no one was changing jobs."

One survey, Professor Kyvig says, showed that 35 percent of the population under age 25 was unemployed in 1931. That was before the 1935 Social Security Act, which required states to pay unemployment compensation to those who qualified.

Extension of unemployment benefits

Since July 2008, Congress has voted four times to extend unemployment-benefits programs, so that some without jobs can receive additional weeks of help. Congress passed the most recent extension last month. It also continued a $25 weekly supplement, available to all 10.8 million benefit recipients.

According to an analysis by the National Employment Law Project (NELP), the December extension allowed some 2.3 million to continue receiving unemployment benefits. It is scheduled to expire in February.

"Ideally, we would like to see these benefits continued through the end of the year," says Christine Owens, executive director of NELP in Washington. "Otherwise, we will again be in a situation where millions of unemployed workers would reach the end of their benefits and would just fall off a cliff."

For many of the long-term unemployed, the extension of benefits is crucial. "They are keeping my family afloat," says Sims-Bowles in Pasadena. "The $425 a week that I'm getting basically pays for food and gas and incidentals. I feel very blessed to have anything."

Those out of work for a long time have learned to scrimp. In Framingham, Mass., discretionary income is very limited for Kate Corrigan, who was laid off nine months ago from a recruiting job in the high-tech sector. "You don't go out to dinner, you don't take a vacation, you are very watchful of everything you do," Ms. Corrigan says.

When a job is advertised, the competition is fierce. Nationally, there are 6.3 job seekers for every job opening, NELP estimates.

Sally Kennamer, who has been out of work since August 2007, has experienced that firsthand. The resident of Grand Rapids, Mich., who is searching for a job as an administrative assistant, estimates that she's sent out thousands of résumés. But she's had only three interviews.

If she could get a foot in the door, she says, she would tell potential employers that she's loyal and that in her nine years at her prior job, she missed only two days of work because of illness or other personal matters. "But I'm competing with so many people, it's hard to tell your story," she says.

A support system

People who have been out of work for a long time need some kind of "community" to support and encourage them, says Elsa Bengel, executive director of Training Inc., a program of the YMCA of Greater Boston. The group works with "middle skill" workers, such as support and service staff.

"They need emotional support as well as skills," Ms. Bengel says.

Toward that end, her organization posts the résumés of the people they are working with on a wall. After someone finds work, the person getting the job rings a bell, and Training Inc. places a "HIRED" sticker on the résumé. "We celebrate. Jobs are miraculous occurrences," she says.

And it gives encouragement to those still searching. "There was a woman who had stopped looking," Bengel recalls. "But then she came back and looked at people in her group who had gotten jobs. We tell them they have to work at this every day."

Some professional coaches for the unemployed counsel them to remain engaged, talking to former colleagues and following up at companies that turned them down earlier. "I say to people, 'Stay in the game,'" says Jeffrey Redmond, a partner at New Directions, a company in Boston that coaches senior executives. "The conditions will improve, and the people who are in the game, stayed active, spreading word about their credentials and capabilities, will be the first considered."

Mr. Redmond's firm is working with 10 people who had been general counsels at various corporations.

One of those is Jack Friedman of Princeton, N.J., who lost his job a year ago as a result of a merger at a satellite-communications company. Since then, he's been looking for a senior-level job at a communications, Web, or media company. "It's been very difficult. The jobs just haven't been there," he says.

Mr. Friedman says he's trying to be patient and not to take anything personally. "It's like being in sales: You have to go through a lot of rejection," he says. "You have to view it as an opportunity to turn a 'no' into a 'yes.' "

Sims-Bowles is trying to remain positive as well. "I am ready to roll up my sleeves and do whatever," she says. "I would like to work for the rest of my life."

-----

Follow us on Twitter.