How US women transformed the Olympics

Loading...

Roseanne Montillo, a literature professor at Boston's Emerson College, is drawn to the morbid and macabre. In 2013, her book "The Lady and Her Monsters" tracked the spooky science that helped spawn Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein." Two years later, she profiled a young murderer's shocking spree through 19th-century Massachusetts in "The Wilderness of Ruin."

So how did she end up writing an inspiring book about courageous female American runners who fought bigotry, sexism, and even a sexually aggressive Adolf Hitler in the 1920s and 1930s?

It came during her research for the second book. As she pored over newspaper archives in search of sensational stories about the fate of her then-famous subject, she found articles about national trials for female runners in New Jersey.

"I was curious to see if they'd make it and become the first women in the Olympics in 1928," Montillo says.

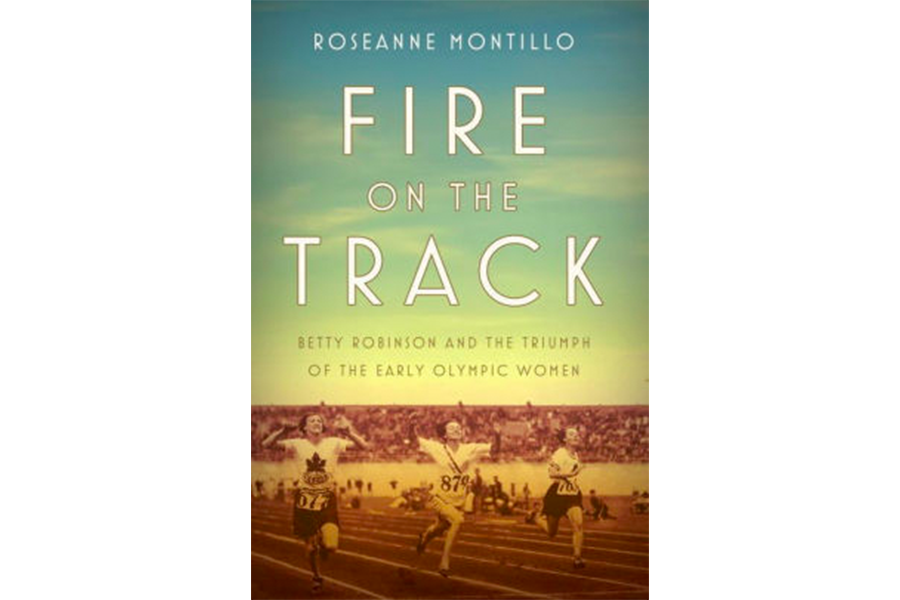

They did. Though they faced more twists and turns than a cross-country trail, this handful of young women helped transform female sports from an also-ran into a real athletic powerhouse. Their story so inspired Montillo that she profiled these groundbreaking runners in the book Fire on the Track: Betty Robinson and the Triumph of the Early Olympic Women.

"They were very courageous," Montillo said in an interview with the Monitor. "I give them credit for having the strength to be vulnerable in front of so many people who are taking shots at you."

Q: It seems like plenty of both men and women at that time despised the idea of female athletes, especially runners. What was their problem?

They thought running was predominantly a male-only sport, and women couldn't physically do it. They believed women's reproductive organs would fall out, they'd start looking like guys, and take on the shape of men.

They also worried that they'd take on male tendencies. They would act like men and enjoy being men.

And since this was the 1920s, they were very much afraid women would get away from their purpose – to get married and have children. No one would want to marry a woman like this.

It was just such a mess.

Q: In the shadow of the male-only Olympics, women held their own athletic competitions. How did they turn out?

They were huge, well-organized, and well-attended, with women coming from all over the world.

Women are good at organizing things when they get together, and they ended up taking a little of the limelight away from the actual Olympic Games. It wasn't what they intended, but it happened.

The organizer of the women's events said we'll continue to do this – get bigger, attract attention and be in direct competition with the Olympics – unless you let us in there. The International Olympic Committee had to come to some kind of understanding.

Q: What did these runners have in common?

They were all very determined, all hard workers. And with the exception of Betty Robinson, they'd come from somewhat similar backgrounds.

They were outsiders, not exactly the most popular kids in school, and they were misfits in their own way. They knew that their way of rising above their status was to run. Running was going to provide that opportunity.

It wasn't a pastime for any of them.

Q: You reveal that runner "Babe" Didrikson, one of history's most well-known female athletes, could be quite an unpleasant person. What was her story?

She rubbed people the wrong way. She could be slightly off-putting with her remarks, and she was a bit of a racist.

She was also very strong and assertive. She wanted to be equal to the guys: If guys are treated in a certain way, why should I be treated any differently?

Q: What sort of challenges did the other runners face off the track?

Betty Robinson's challenge was overcoming a terrible plane crash. People believed Helen Stephens was a lesbian, which she was. People thought Stella Walsh was a man. [The truth was more complicated.] And Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes didn't only deal with being women in a male-dominated sport. They were also African-American.

They all had to deal with their own issues. But they were also in a group, which gives you strength. You gain more self-confidence even if you don't particularly care for or like the others in the group. It gives you a little more power over whatever comes along.

Q: What is the legacy of these women?

Their legacy should be one of determination. They had to overcome brutal treatment, and they had the power to go out there and say, "I'm going to shut all out all of that and run."