How hard is it to impeach a president? Ask Andrew Johnson.

Loading...

Donald Trump will take the presidential oath of office on Jan. 20, and it won't be long before at least a few of his political enemies in Congress solemnly swear to remove him from office.

If they were to succeed, it would be the first time ever that an American president has been both impeached (by the House) and removed from office (by the Senate).

The first impeachment, of President Andrew Johnson in 1868, has largely been lost to history. Still, his impeachment was a wild affair, pitting an angry and hateful president against an infuriated Congress in a pitched battle over the legacy of the assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

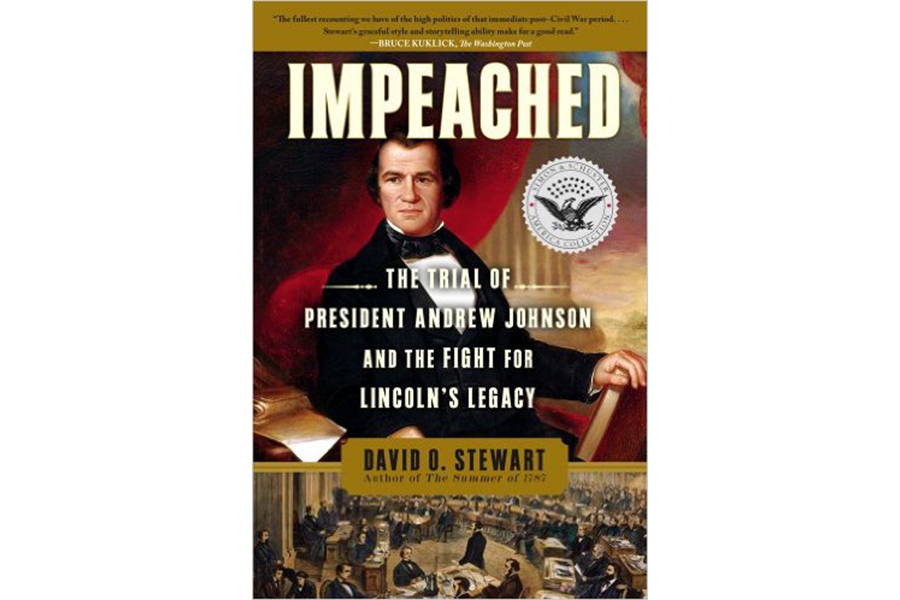

Historian David O. Stewart unravels the whole remarkable story in 2009's Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy.

Stewart knows more than most about this process: He represented Judge Walter L. Nixon, Jr., of Mississippi, who was impeached and removed from office by Congress in 1989.

As Inauguration Day nears, I asked Stewart to talk about what happened in 1868 and what we can learn from it today. "It set the bar for impeachment pretty high," he says. "You had a president whom a lot of people were extremely unhappy with, but he still stayed in office."

Q: Why do we have a process to remove the president?

The framers were very mistrustful of all forms of government power. They felt that we needed a way to rid ourselves of an executive who'd proved to be dangerous, not right for the job. But they struggled about how to do this.

A number of the delegates were very learned in old English traditions, and they sort of dug up this impeachment remedy. They adapted it and made it particularly American, viewing it as a peaceful, legalistic way to deal with what they viewed as a real risk.

There's this wonderful moment when Ben Franklin first hears about the impeachment idea. He exclaims with apparent pleasure that this is a great idea, 'When we have a bad president, we won't have to kill him!' He's saying that in other situations, assassination might be justified.

Q: Andrew Johnson was a Democrat who served as vice president under Lincoln, a Republican president. While he was pro-union, he was also pro-South in many ways, and became president just as the Civil War had ended. What kind of America did he want to see?

It's a complicated business. At some level, Johnson thought he was pursuing Lincoln's legacy. He did not want a vengeful or vindictive peace with the South. But in implementing that idea, Johnson ended up basically alienating the North.

He himself was essentially a Southerner. He was from Tennessee, never saw anything wrong with slavery and was virulently racist himself.

He imposed such mild conditions in the Southern states that he lost any claim to legitimacy as far as many Northerners were concerned. They thought he was abandoning the causes that their husbands, fathers, and sons had died for, and it became an extraordinary bitter time.

Q: He didn't help things by being so difficult, did he?

He was hard to like, with a very self-righteous attitude. He'd come up from nothing, had no advantages in life, and had never attended school for a day.

You can often understand a historical figure through his or her humor, but Johnson had none. I looked for anecdotes or funny events, but he seems to have been an incredibly uncongenial guy.

I think it was his bodyguard who described him as the best hater he ever knew. And President James Polk described him as vindictive and perverse.

Q: Why did he become Lincoln's running mate in the first place?

Lincoln had picked him purely for political convenience. He was making what we'd now call a move to the center, looking to someone who'd appeal to those who felt less supportive of the war. It didn't sink into him what kind of president Johnson might be.

Q: Johnson went out of his way to make life more difficult for former slaves. Then Congress decided to set a trap by making it illegal for him to fire his own cabinet members without congressional approval. How'd that play out?

The statute said a violation of the law was a high crime and misdemeanor. When he fired the secretary of War without Senate approval, he knew he was daring them to impeach them. He wanted the fight. Otherwise he wouldn't be able to do what he wanted to.

Q: But somehow he won by inches, keeping his job – but only for a few more months because an election was coming. What impact did the impeachment have, then?

It probably ended up staying his hand. He lost a lot of power because it had been so close, and he had to make a few deals with folks who were wavering.

There's a lot of evidence of bribery. Both sides were willing, but you'd have to say it was the winning side that probably did it. The evidence is not totally conclusive, but there a fair amount of it. It's my belief that senators took money to vote for Johnson.

Q: What's the legacy of the Johnson impeachment?

At the end of the day, even though it looks like a judicial proceeding, most senators ended up voting politically. They're political animals. But when you're talking about the president, it should be a political decision, since you're reversing the will of the people.

Q: Are there lessons for the new president and administration?

The incoming president needs to keep the confidence of the people.

Look at the Clinton impeachment: I don't think anyone argues he didn't lie under oath. But enough people were confident that he was a competent president, and he wasn't removed.

As for those who favor impeachment, I'd say hold your horses, wait. There's got to be a reason other than that you think [the president] is a terrible guy. People need a reason.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is a board member and immediate past president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.