10 writers I'm most grateful for this Thanksgiving

Loading...

As another Thanksgiving arrives, let’s give thanks for authors, those curious souls who make the books that sustain, enlighten, and entertain us readers from year to year.

Quite often, the potential gratitude of readers is the biggest motivation for an author to undertake a book in the first place. Authors who write for fame or money, after all, will likely be disappointed.

The overwhelming majority of authors can’t make a living just by writing books. Scan the author bios on the dust jackets along your bookshelf, and you’ll notice that most authors pay their bills with another job – usually, as a professor or journalist. They write books away from the office – in early morning, late evenings, on weekends. Just think of it: our literature advanced day by day as a form of moonlighting – by writers working through fatigue and distraction to make a manuscript into a reality.

The obstacles to authorship are large, the prospect of reward quite small. Given that reality, it’s an abiding miracle of our culture that books continue to get written at all. It’s not something to take for granted, in other words, as readers count their blessings today.

Between servings of turkey and pumpkin pie, try making a mental list of authors for which you’re especially grateful. Here are 10 of mine:

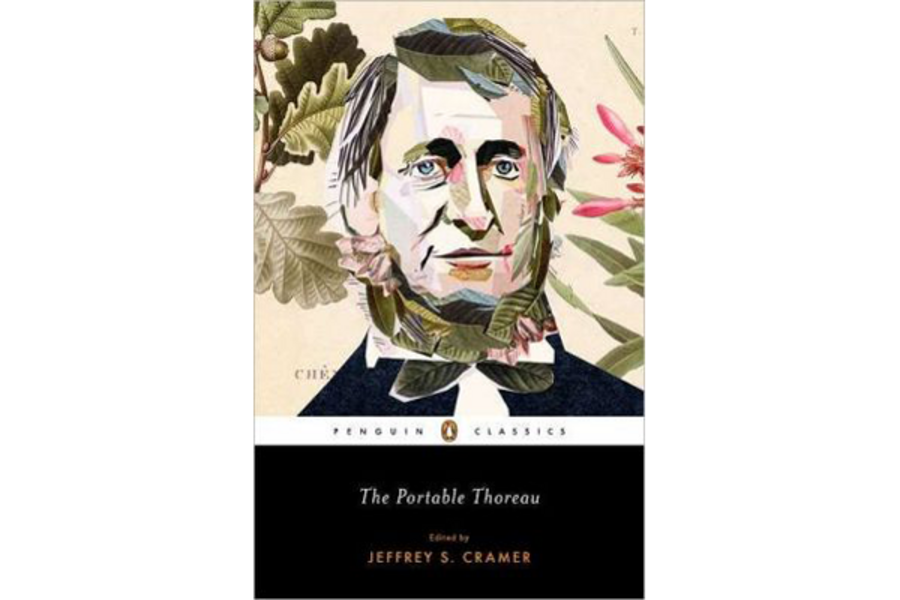

1) Henry David Thoreau. When I first read Thoreau in college English class, he nearly bored me to death. I tried him again during a summer internship in Washington D.C., banking on his snooze factor to help me get to sleep. But in revisiting him that summer, I found things to like. Thoreau’s alertness to wonder just beyond his doorstep inspired me to look more closely at the good things at arm’s reach within my own life. Isn’t that what Thanksgiving’s all about?

2) Eudora Welty. As a young reader, I thought of literature as something that grew only in the world’s great capitals of culture and power – New York, Paris, London. Welty, writing profound and graceful novels, short stories and criticism from her native Jackson, Mississippi, showed me an alternate possibility – that a writer could also develop his imagination and craft in less iconic locales.

3) H.L. Mencken. In my early days as a student, I thought of writing as something important, challenging and grand. Mencken, whose writing I discovered through a castoff volume on a rummage sale table, showed me that writing could also be fun. Mencken’s ribald style made him a sensation in the 1920s, and he still holds up today, as evidenced by the new Library of America edition of his “Days” trilogy.

4) E.B. White. As a college journalism student much impressed by the bombastic style of H.L. Mencken, I thought that all great writing had to be loud. But coming across a collection of White’s essays in a bookstore, I realized after reading his quietly expressed sentences that an author doesn’t always or even usually have to shout to be heard. I’ve been a fan ever since.

5) Elizabeth Bishop. After graduating college, I felt relieved that I’d never have to read poetry again. Poets often seemed to hide their meaning under the surface, and as a journalism grad who aspired to tell it like it is, I found that kind of sublimity a waste of time. But while spending a groggy afternoon at home recovering from minor surgery, I heard an Elizabeth Bishop poem, “One Art,” on TV and fell under the spell of its music. I also came to understand that poetry often expresses meaning by what’s not said – a form of sorcery that’s made me a poetry fan ever since.

6) Lewis Thomas. When my high school science teacher suggested that I read “The Lives of a Cell” by Lewis Thomas, I balked. Why would a liberal arts enthusiast waste his time reading a book by a doctor about biology? But from the first page, I was enthralled by Thomas’s lucid conversational style, his sense of humor, his abiding wonder. Thomas taught me that there are no boring subjects – and that any reader who aimed to be educated should learn about science, too.

7) Bill Bryson. A friend gave me a copy of Bryson’s “A Walk in the Woods” many years ago, and I’ve been a fan since that day. “The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid,” Bryson’s comic memoir, is an instant cure for the blues, but be warned: The first time I read it, I laughed so hard that I almost fell out of my bed.

8) Virginia Woolf. Woolf once observed that even harder than expressing oneself as a writer is being oneself. Woolf mastered both skills, and “The Common Reader,” which assembles her best literary criticism, is my gold standard for what writing should be. I chafe at the frequent classification of Woolf as a “women’s writer”; she was a genius who belongs to us all.

9) David McCullough. McCullough worked as a magazine writer before turning to history books, and he brings a journalist’s sense of urgency to his accounts of the American Revolution, Harry Truman, the building of the Panama Canal. That’s why his books are so engaging, and why they occupy a place of honor on my shelf.

10) Verlyn Klinkenbourg. Klinkenbourg, until last year a member of The New York Times editorial board, reminded readers in his essays about his upstate New York farm that news can come from unlikely places – the shape of a cloud, the gaze of a cow, the wind working its way through trees and pastures. Too bad that his “The Rural Life” column no longer appears in the Times, although his best work, assembled in two “Rural Life” collections, is a continuing instruction in how to write well.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”