New data says less than 3 percent of children's books surveyed in 2013 were about black people

Loading...

It’s a jarring statistic for anyone cognizant of the power of books, especially books for children: Of some 3,200 children’s books surveyed in 2013 by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Education, only 93 were about black people.

In a country in which African Americans comprise at least 13 percent of the population, less than 3 percent of the new children’s books received by the Center in 2013 were about black people and even fewer were by black authors – about 2 percent.

Beginning in 1985, the center began documenting the number of new children’s books written by or about African Americans that they received at the library each year. The numbers were dismal then – out of 2,500 children’s books published in 1985, only 18 were by black authors – and remain so today.

In 1994, the center began also tracking books by and about American Indians, Asians, and Latinos and found similarly dispiriting figures: Of the 3,200 children’s books it surveyed in 2013, 93 were about blacks, 34 about American Indians, 69 about Asians and Pacific Americans, and 57 about Latinos.

Perhaps the most troubling trend is how little the numbers have changed since the center began tracking them in 1985 and 1994, for blacks, and other minority groups, respectively.

Why is this so troubling?

Books shape our understanding of the world and our understanding of ourselves, an occurrence even more pronounced in children. When parts of our society are scarcely represented in the books we read, we’re less inclined to know, relate to, and value those groups. Even more troubling, when minority readers, especially children, don’t see themselves represented in the books they read, they don’t receive the validation and affirmation of self that reading provides.

As children’s book author and illustrator Christopher Myers wrote in an op-ed in the New York Times, “One is a gap in the much-written-about sense of self-love that comes from recognizing oneself in a text, from the understanding that your life and lives of people like you are worthy of being told, thought about, discussed and even celebrated.”

The raw numbers of the CCBC’s study are difficult to comprehend – perhaps especially so for white readers – unless considered from the perspective of black children struggling to see themselves in the white-dominated worlds of the books they read.

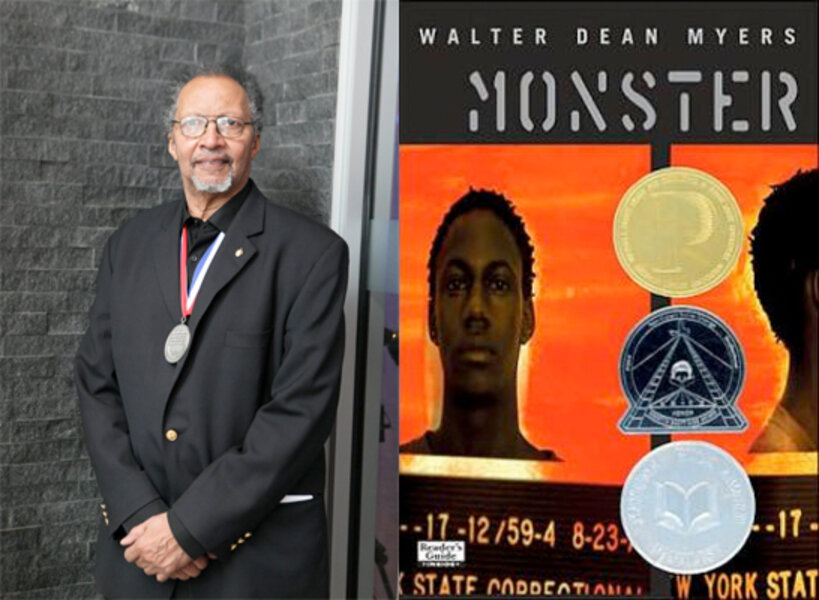

Children’s book author Walter Dean Myers, author of “Monster” and a former Library of Congress National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, recently told his story in a poignant op-ed in the Times.

Myers says he grew up in Harlem reading what many kids read – comic books, bible stories, “The Little Engine That Could,” “Goldilocks,” then Robin Hood, and onto Shakespeare, Mistral, and Balzac.

“As I discovered who I was, a black teenager in a white-dominated world, I saw that these characters, these lives, were not mine,” Myers writes. “I didn’t want to become the 'black' representative, or some shining example of diversity. What I wanted, needed really, was to become an integral and valued part of the mosaic that I saw around me.”

With that realization, he stopped reading, stopped going to school, and joined the Army. His post-Army days were “a drunken stumble through life,” rescued, ultimately, by writing and books.

Myers read “Sonny’s Blues,” by James Baldwin, a story about black people in Harlem. Myers “didn’t love the story,” but it was life-changing nonetheless.

“By humanizing the people who were like me, Baldwin’s story also humanized me. The story gave me a permission that I didn’t know I needed, the permission to write about my own landscape, my own map.”

To fill the void he encountered as a youth, Myers began writing his own children’s books about black kids. Black kids accustomed to stories by white authors about white kids in white environments are often elated by his books, he says.

“They have been struck by the recognition of themselves in the story, a validation of their existence as human beings, an acknowledgment of their value by someone who understands who they are.”

It’s a story that humanizes the startling statistics in CCBC’s survey – and one we hope readers remember as they buy, borrow, read – and write – books for children.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.