Should prison inmates be allowed to read whatever they choose?

Loading...

How much freedom should inmates have to read?

That’s the question on some minds as a string of incidents has exposed the unlikely challenges faced by prison libraries – making strange bedfellows of the books and law enforcement communities along the way.

The latest is a decision by the 1st District Court of Appeal in San Francisco, which recently overturned a previous ruling barring an inmate of a state prison from receiving a book he requested deemed problematic by prison officials. The book in question was “The Silver Crown,” by Mathilde Madden, which has widely become known as “werewolf erotica,” and was considered too sexual by corrections officers.

“Prison authorities had a legitimate penological interest in prohibiting inmates from possessing sexually explicit materials,” Justice James Richman wrote, but in this case, they overstepped their powers and engaged in an “arbitrary and capricious application of the regulation,” Richman said, as reported by Salon.com.

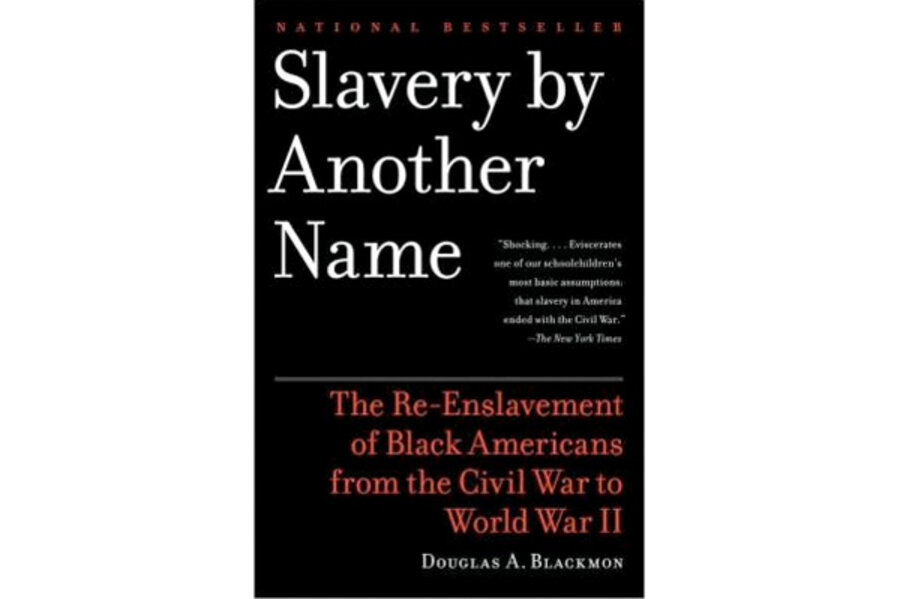

That decision follows news of an Alabama prison that barred one of its inmates from reading the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans From the Civil War to World War II” by Douglas Blackmon. A 2011 suit by the American Civil Liberties Union charged a South Carolina prison with denying its inmates all reading material other than the Bible.

(Meanwhile, a prison library at Guantanamo Bay has some 18,000 books, along with periodicals, DVDs, and video games, from which detainees can choose two each week for a loan period of 30 days, as reported in a recent fascinating article by the New York Times exploring the books and prisoner preferences at Gitmo. Besides religious books in Arabic, popular fare there includes Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “News of a Kidnapping,” Danielle Steel’s “The Kiss,” and adventuring magazines, which allow detainees rare glimpses of nature.)

While some in the books world have decried the book confiscations, maintaining order and security is paramount at corrections institutions. As such, the controversial incidents raise some complex questions about prisoners’ rights when it comes to reading as well as corrections officers’ rights when it comes to preventive and punitive measures to maintain order and security. For, while inmates surely have some First Amendment rights such as freedom of speech, they also surrender some of their First Amendment rights upon incarceration.

As the website FindLaw explains, “Inmates retain only those First Amendment rights... which are not inconsistent with their status as inmates and which are in keeping with the legitimate objectives of the penal corrections system, such as preservation of order, discipline, and security.”

It is for this reason prison officials can screen and open mail directed to inmates, for example.

But the strictures governing inmate rights with regard to reading leave many questions. Who decides which books are inconsistent with the “preservation of order, discipline, and security” and why? What makes one book problematic, one innocuous, and one potentially remedial or rehabilitative? In short, how much freedom should inmates have to read?

Let us know what you think.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.