James Agee's legacy changes with discovery of new text

Loading...

This week, with the publication of James Agee’s “Cotton Tenants: Three Families,” literary sleuth John Summers is trying to correct a small but important part of Agee’s literary history.

Agee, who died in 1955 at age 45, is perhaps best known as the author of “A Death in the Family,” a beautiful, posthumously published novel based largely on the author’s early loss of his father.

But Agee (pronounced Ay-gee) is also famous for one of the most curious incidents in American letters – an episode that the new release of Agee’s long-forgotten “Cotton Tenants” is aimed at clarifying.

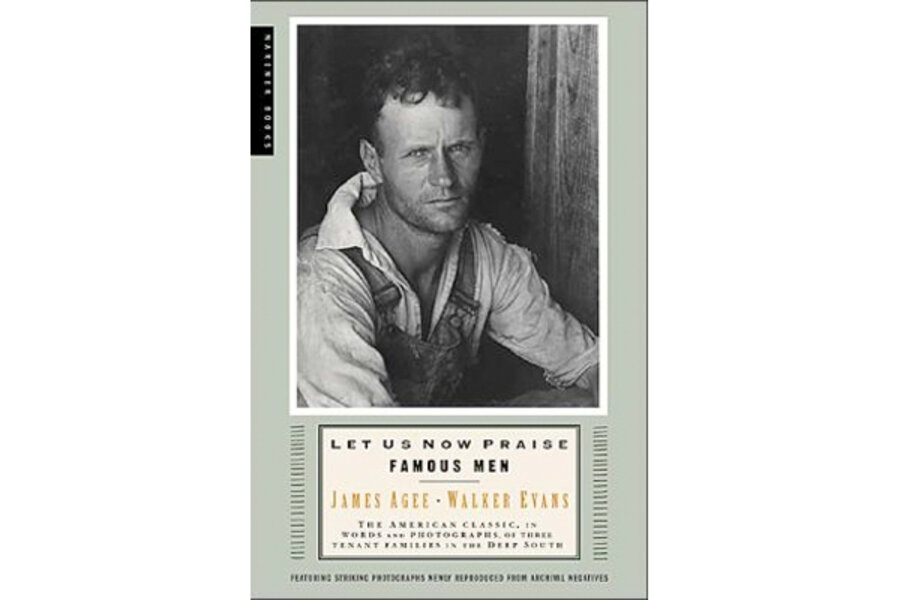

In 1936, Fortune magazine publisher Henry Luce sent Agee and photographer Walker Evans to do a slice-of-life story about poor Alabama farmers. But Fortune rejected the story, which eventually led to “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” a book that combined Agee’s cryptic, stream-of-conscious narrative with Evans’ haunting pictures of Depression-era families to become a landmark of social documentary.

Over a couple of generations, while reading “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” even many of Agee’s admirers had little doubt about why Fortune rejected Agee’s peculiar material. Asked to write about “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” several years ago, essayist Phillip Lopate said that the book “is often glibly spoken of as a classic, but if it is, it must be one of the most unread and unreadable classics, which educated people would rather compliment than endure.”

But in 2010, Summers, who edits The Baffler literary journal, became aware of an Agee typescript that seemed, based on circumstantial evidence, to be the original – and only known version – of the piece that Fortune had declined to publish. Interestingly, the typescript contains a much more conventional account of Agee’s Alabama travels than the story within “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

Summers’ discovery calls into question the long-held assumption that Fortune rejected Agee’s Alabama travelogue because of the article’s unrelenting experimentation. What now seems more likely is that “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” is a radically reimagined version of Agee’s Alabama experiences, and not merely a book version of his magazine piece. The unpublished magazine piece, although it contains flashes of Agee’s eccentric vision, is a much more conventional piece of journalism than “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

Summers published a part of the rediscovered typescript in an issue of The Baffler. Now, the entire typescript has been published, along with Evans’ related photographs, in “Cotton Tenants: Three Families."

The new book is a more accessible take on Agee’s Alabama trip, offering a sublime showcase for his frequently masterful prose style. Agee describes a poor tenant farmer’s day, for example, as “strung between two flowerings of a lamp; slung from its meals as from three wooden pegs; and mostly work; and the leisure mindless.”

But in other parts of Agee’s narrative, he proves maddeningly opaque, and a few of his sentences read like riddles, anticipating the mystical pronouncements of “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

Listen to this, for example: “Human life, we must assume in the first place, is somewhat more important than anything else in human life, except, possibly, what happens to it.” Huh?

Even so, the virtues and complication so “Cotton Tenants” stand on their own, making the book memorable in its own right, beyond its connection to “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

As reviewer John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote in an advance review of the “Cotton Tenants,” it’s “not just a different book; it’s a different Agee, an unknown Agee. Its excellence should enhance his reputation...”

Danny Heitman, an author and a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is an adjunct professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication.