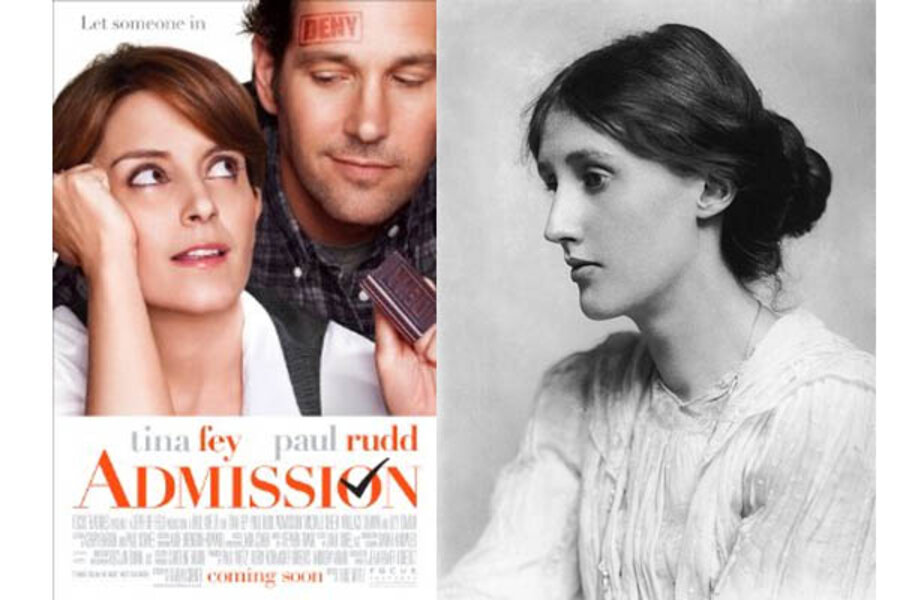

Hey, 'Admission': Quit using Virginia Woolf as a punchline!

Loading...

Thanks to “Admission,” a new film comedy starring Tina Fey as Portia Nathan, an admissions officer at Princeton, Virginia Woolf is getting a renewed profile – although not necessarily the kind of attention that promises to win Woolf new readers.

Among the comic elements in the story is a love triangle involving Portia, her English professor boyfriend (Michael Sheen), and a Virginia Woolf scholar played for laughs by Sonya Walger.

“That the phrase ‘Virginia Woolf scholar’ is used several times as an epithet and a punch line is evidence of the film’s unusually acute interest in academic life and, also, its ambivalence about feminism,” New York Times critic A.O. Scott wrote in his review.

Woolf is a favorite among many feminist literary scholars, and “Admission” seems to reinforce the notion of Woolf as a writer of interest only to women.

That was a widespread misconception before “Admission” ever hit the screen, but one I’d like to dispel. I’ve enjoyed Woolf’s writing for years, and I wince a little each time she’s pigeonholed as a “women’s writer.”

Woolf, a giant of English letters who lived between 1882 to 1941, certainly never aspired to that kind of narrow appeal. In the title essay of her famous collection of essays, “The Common Reader,” Woolf celebrated the universal ideal of the person who “reads for his own pleasure rather than to impart knowledge or correct the opinions of others. Above all, he is guided by an instinct to create for himself, out of whatever odds and ends he can come by, some kind of whole – a portrait of a man, a sketch of an age, a theory of the art of writing.”

Pleasure is an abiding gift of Woolf’s writing, and that quality doesn’t always seem evident when she’s promoted as a “women’s writer.” The term tends to reduce her work to a political gesture, something to be tolerated out of civic obligation rather than embraced for its promise of joy.

Woolf dealt with serious topics, to be sure, but I’d like newcomers to her work to know just how fun she can be on the page. She had a sublime gift for metaphor, a genius for rendering abstraction into lively, concrete language. Here, in an essay on the great French essayist Michel de Montaigne, Woolf discusses the difficulty of trying to write about a thought as it moves through one’s head: “The phantom is through the mind and out of the window before we can lay salt on its tail, or slowly sinking and returning to the profound darkness which it has lit up momentarily with a wandering light.”

That’s just like Woolf – turning an act of intellect into something tangible, sensual, full of color. She’s invariably a delight to read, whether she’s drafting a letter, writing an essay or book review, or penning a novel.

While novels such as “Mrs. Dalloway” and “The Waves” have secured Woolf’s place in posterity, I’m partial to her nonfiction, including her correspondence. She’s a great gossip about other writers, and I laughed out loud while reading a letter in which Woolf described some of Henry James’ writing as “the laborious striking of whole boxfuls of damp matches.”

What I also like about Woolf is that she never forgets the first obligation of a writer – to shake the reader awake with the gift of surprise. Though I’ve read her for years, Woolf continues to catch me off guard, as when I combed the titles at a recent rummage sale and came across “Flush,” in which Woolf constructs an entire biography of poet Elizabeth Barret Browning’s cocker spaniel.

The book is on my nightstand right now, and I can’t wait to start it. I wish more readers, men and women, knew the Virginia Woolf that I do – as a writer to read because you want to, not because you have to.

– Danny Heitman, an author and a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is an adjunct professor at Louisiana State University’s Manship School of Mass Communication.