'After Visiting Friends': Michael Hainey talks about his journey into his father's past

Loading...

When one of their own passed away suddenly in 1970, the newspapers of Chicago remembered him in obituaries as a savvy young copy editor who left a widow and two little boys. He died, it was said, "after visiting friends."

The nosy parkers at the papers didn't feel the need to provide any more details. Their natural curiosity had suddenly vanished, gone like last week's fishwrap.

The family went on, the boys grew up, and the true story of a mysterious death remained a closely held secret. Then one of the boys, now an editor at GQ Magazine, decided to uncover the truth regardless of how painful it might be.

What actually happened late one night? Were there actually any "friends" or was that a bit of newspaper subterfuge, a bid to protect a buddy's reputation? What did people know, when did they know it and how could those still alive be coaxed to talk?

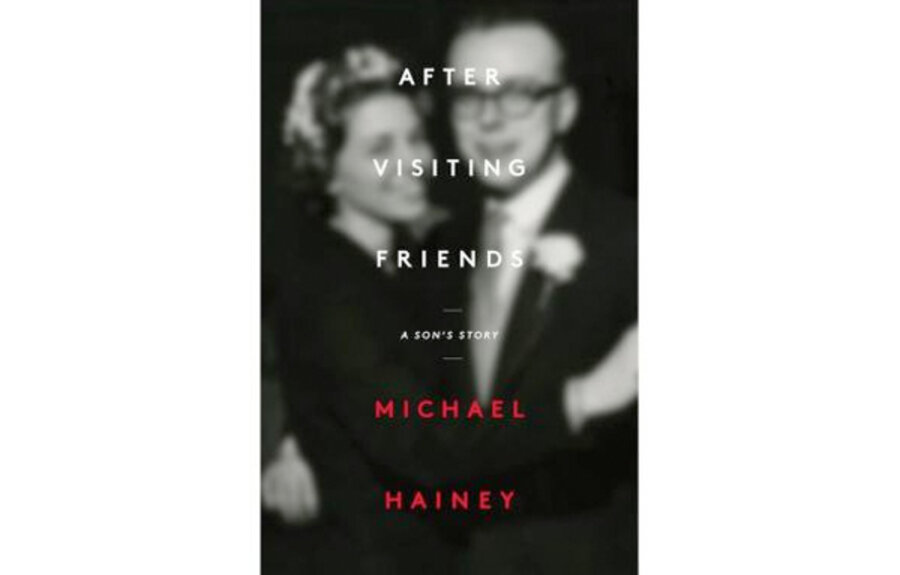

Michael Hainey's tale – part detective story, part memoir, part elegy – unfolds in the captivating and poignant new book After Visiting Friends: A Son's Story. He whips back and forth between the decades in search of clues, finding closed-mouth newspaper journalists (a species previously thought to be mythical) and unhelpful government paper-shufflers who are actually vulnerable to human emotion or at least free coffee (ditto).

Should anyone try to strip bare the past of a parent, especially one who can no longer defend or explain or deflect? I asked Hainey to ponder that question and consider whether mothers and fathers owe the truth to their children.

Q: Why is it so important to understand the lives of our parents?

A: We forget that our identities, our narrative stories that we used to tell ourselves who they are, are bound up in our parents' identities and their stories.

To know our own identify, to know our own stories, I've learned that you have to go into that past, into your parents' past. If you don't know their story, you don't know your story.

Q: What was going through your mind as you launched this detective story, not knowing whether it would hurt you, your mother and brother, or other people?

A: As I say in the book, we all say we want the truth, but that doesn't mean everyone else wants it. I had a lot of fear, and it held me back in different ways and different times.

Q: Did you feel like you were bearing witness to lives lived?

A: I wanted to bear witness to everyone in the book.

I tried very hard to honor everyone living and not living. I wanted to treat anyone I encountered with compassion and humanity: this is a life lived.

Q: You interviewed people who vividly remembered personalities and conversations from more than four decades ago. Were you surprised how they remembered so much?

A: I wasn't surprised. They were young and vibrant back then. These were very vital years for them, and it's a generation that learned to retain its memories. We have to hold onto those stories because that's how we form our identities.

Q: One of the saddest moments in the book comes when your mother bitterly remembers how her married women friends abandoned her, apparently because she became a pretty and available widow – a threat to their husbands. Did it surprise you to look back at that time and see things like that?

A: I forgot what it was really like.

My brother and I couldn't even remember a divorced family in our neighborhood. People were still two-parent families and very nuclear. To be a single mother in our neighborhood was just unheard of.

I also see how far we've progressed. I went to school the day my father died, and the day after the funeral I was back at school with my brother.

There was no such thing 43 years ago as grief counselors or school psychologists. I'm sure that if someone with a trained eye had seen me, they would have thought, "This boy is having problems adjusting."

Q: But no one noticed?

A: As my mother said tearfully at times, "I didn't know any better."

Q: Do you think parents have a right to keep big secrets about themselves from their kids?

A: Sure. You have a right to your secrets. But if someone asks a parent a question in search of a truthful answer, there's a responsibility to tell that answer. Whether it's a kid or someone in their 40s, I don't think anyone should ever lie to someone actively.

But unless someone chooses to ask you about it, you don't need to reveal it.

I have a friend whose father told her when she was a teenager that he was having an affair: Don't tell your mother.

She said: "I didn't want to know this, why did you tell me this?"

What are you supposed to do with that? Does a kid want and need that information?

Q: Do you ultimately think you made the right choice by uncovering what happened?

A: I learned some not-good things, and I learned a lot of good things. Ultimately, the book resonates with readers because it inspires a lot of conversations with parents while they are still alive.

That's a really positive powerful gift of the book: It's never too late. What do you really know about your parents? We all have families and we all have these secrets. If we look at our lives, once we learn the truth about something we're always relieved.

The truth might be upsetting in the moment, but you never regret you know the truth because it allows you to move forward in your life. [The problem comes] when we don't know the truth, or choose to not hear the truth, when we know we're compromising and choosing to tell ourselves a lie or allow a lie to have life.

We need to go into our past sometimes before we can go forward.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.