Amazon struggles to get its books onto the bestseller charts

Loading...

If Amazon is the Hercules of the book world, the leviathan who overshadows all, then publishing is its Achilles’ heel.

Despite its almost mythical dominance in book retailing, Amazon has struggled mightily to crack the publishing business. While it sells millions of copies of other publishers’ books, Amazon can’t quite seem to get its own books off the ground and onto the bestseller charts, according to a recent Wall Street Journal piece that examined the online retailer’s publishing woes.

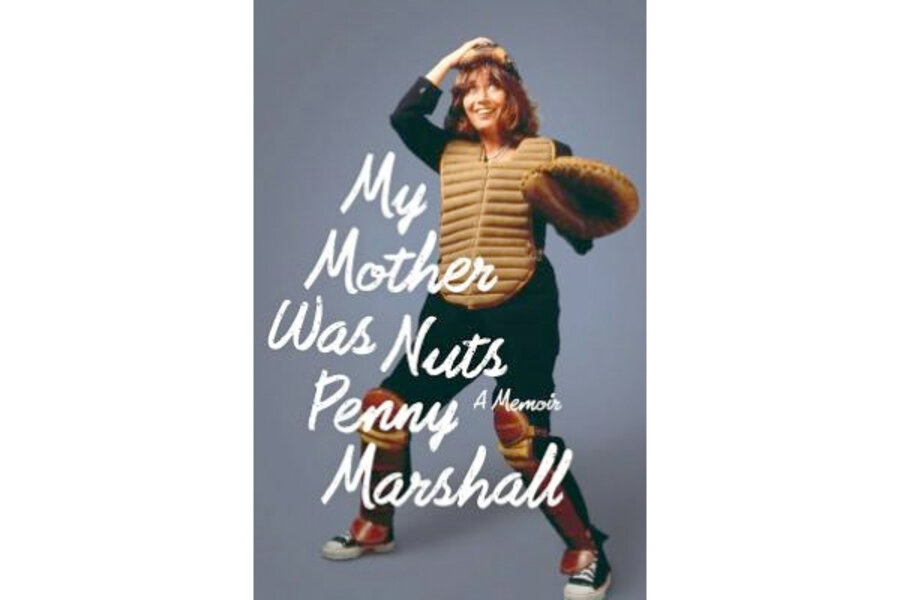

Case in point: Penny Marshall’s memoir, “My Mother Was Nuts.” The memoir by the actress and director was published by Amazon and was slated to be one of its biggest titles for fall. “In its first four weeks of sale it has sold just 7,000 copies in hardcover, according to Nielsen BookScan,” reports the Wall Street Journal. “By comparison, actor Rob Lowe’s memoir, 2011’s ‘Stories I Only Tell My Friends,’ published by Macmillan’s Henry Holt & Co., sold 54,000 hardcover copies in its first four weeks.”

Granted, there could be many reasons for the memoir’s failure to sell. “Marshall hasn’t been in the limelight for a while,” writes the WSJ, and, of course, not every memoir strikes a chord. But there’s one considerable culprit for the slow sales of “My Mother Was Nuts" and every other book Amazon publishes: “its severely limited availability.”

If readers wanted to find “My Mother Was Nuts” in a bricks-and-mortar store, or simply stumble upon it, the way some books are discovered, they would be hard-pressed to do so. The memoir wasn’t stocked in any of the almost-700 Barnes and Nobles stores across the country, nor in Wal-Mart or Target stores. Most independent booksellers don’t stock the book, and the e-book version wasn’t carried by stores operated by Sony, Apple, or Google. Just about the only place a reader is guaranteed to find the memoir is at Amazon.com.

That’s largely due to a deliberate boycott of Amazon books by retailers resentful of the mega-online retailer’s Herculean dominance of the books market. In a move called a “declaration of war,” Barnes and Noble announced early this year its decision to yank Amazon-published books from its shelves.

“Barnes & Noble has made a decision not to stock Amazon published titles in our store showrooms,” Barnes & Noble chief merchandising officer, Jaime Carey, wrote in an email in February 2012. “Our decision is based on Amazon’s continued push for exclusivity with publishers, agents, and the authors they represent.”

The tactical move was “an attempt to cut off access for the online books behemoth that [Barnes and Noble] says ‘undermined the industry’ by signing exclusive agreements with publishers, agents, and authors,” according to a February 2012 Chapter & Verse post.

Amazon is feeling the pain now: the Penny Marshall memoir is the first big Amazon title to be published since the boycott began. And though all retailers are not boycotting Amazon books, “the company’s status as a competitor is clearly a factor for some,” writes the WSJ. “I don’t want to be a showroom for Amazon,” Mitchell Kaplan, owner of three Books & Books stores in Florida, told the Journal.

Authors are taking note. After a string of deals with authors like Deepak Chopra, Timothy Ferriss, and James Franco in the spring of last year, Amazon, which entered publishing quietly in 2009, appears to be struggling to attract big names. The Barnes & Noble boycott, it seems, has slowed the number of big-name books Amazon has been able to sign.

“It’s panic time,” Siva Vaidhyanathan, a professor of media studies and law at the University of Virginia, told the WSJ. “The notion that a company as powerful as Amazon has such a tremendous amount of influence on what we read, how much money authors make, and the formats that books appear in is really scary to the book industry and other industries as well.”

In other words, the Herculean Amazon’s very strength has become its greatest weakness.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.