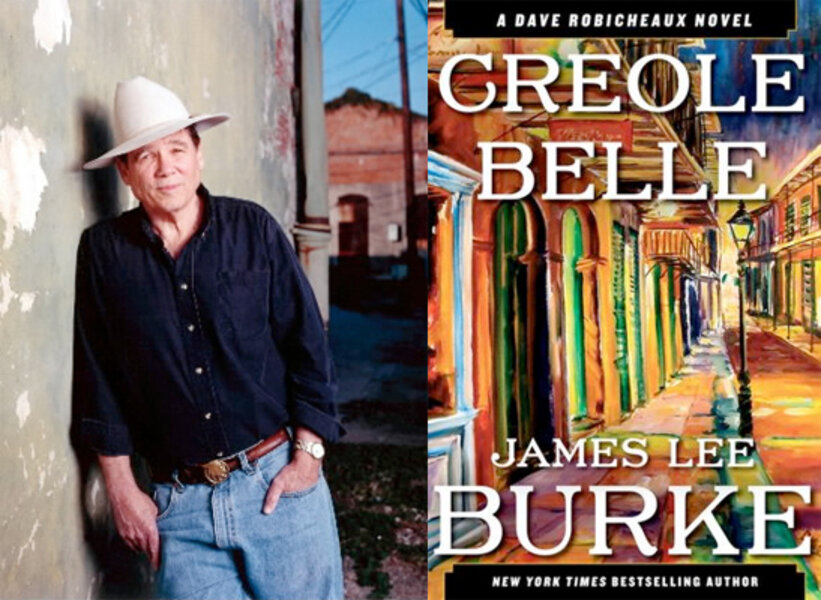

James Lee Burke discusses 'Creole Belle' and the end of 'traditional' America

Loading...

When readers last saw Cajun detective Dave Robicheaux, in the final pages of the 2010 novel "The Glass Rainbow," he had just been shot in a bloodbath at his home on Louisiana’s Bayou Teche.

This month, Robicheaux returns in James Lee Burke’s 19th book in the series, "Creole Belle." It picks up where the previous book left off, with Robicheaux in a recovery unit in New Orleans. Morphine clouds his head and, even more than usual, the self-aware detective struggles to separate the past from the present.

Burke, 75, creates lyrical mysteries with what can only be described as deceptive ease. Whether it’s Robicheaux, stand-alone novels, or separate series starring Texas cousins Billy Bob and Hackberry Holland, the themes remain constant. Every novel Burke writes delves into moral ambiguity, the menaces of greed and violence, the degradation of people and land, the juxtaposition of natural beauty and man-made horror and, finally, the sublime joy of human love and loyalty.

No matter his digressions, Burke’s stories retain tight plots amid the languid descriptions and observations of corruption and conceit. Robicheaux made his creator wealthy, taking readers into both rural and urban Louisiana (the detective is a former New Orleans cop who still ventures into the big city) and offering insight on a landscape that is literally disappearing.

Burke spent much of his early life on the Gulf Coast shuttling between Texas and Louisiana and later moved to New Iberia, La., the setting for the Robicheaux books. The author and his wife, parents of four grown children, including crime novelist Alafair Burke, have long split their time between Louisiana and Montana.

Both the author and his best-known character embody Faulkner’s maxim of loving a place “not for the virtues, but despite the faults.”

Consider this observation from Robicheaux in Creole Belle, told once again in his first-person voice:

“In Louisiana, which has the highest rate of illiteracy in the union and the highest percentage of children born to single mothers, few people worry about the downside of casinos, drive-through daiquiri windows, tobacco depots, and environmental degradation washing away the southern rim of the state.”

Burke never shies away from gritty crime patois or slashing violence, but he also slips in enough sociological observation to connect lowly street thugs with equally loathsome politicians and craven corporate executives. And, lest anyone get the idea the novels are preachy, think again. Robicheaux fights criminals, but he fights himself, his boss Helen Soileau and, as a recovering alcoholic, baser instincts and cravings.

If those aspects fail to grab a reader’s attention, the snap in the dialogue does the trick. Robicheaux’s longtime pal, Clete Purcel, offers a typical example in the new book, telling a shady character, “The day you’re honest is the day the plaster will fall from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.”

Burke has no such problems, as he made clear during a recent interview. Following are excerpts from that conversation.

On the origins of the new book: "The two books are actually one novel, one story ["The Glass Rainbow" and "Creole Belle"]. The antagonists represent the same forces, these guys who are degrading the environment. The story dwells on mortality. Not only the mortality of individuals but the end of an era, a generation. At least [from] Dave Robicheaux’s perspective, the end of a traditional America.

He, like me, was born in the Depression. And our generation is transitional one. We’re probably the last generation that will remember what people call traditional America."

On comparing Robicheaux with other characters: "I’ve written three novels about Hackberry Holland. I’ve written a number of books that are outside the Dave Robicheaux series and they don’t receive the same attention as the Louisiana books. I write many different things that maybe people aren’t aware of."

On what he plans to write next: "I haven’t thought about it. I don’t plan very far into the future. I’m writing a very different kind of a book right now. I see two scenes ahead into a novel and I don’t see anything else. I never know how a chapter will end, you see. So the notion of a long-range plan has never existed for me. I don’t mean that isn’t a good way to do things, but it’s never worked that way for me."

On the creation of Dave Robicheaux: "The themes of my work have never changed. I wrote my first novel in my early-20s. And I’m older, certainly, now, but I don’t think much wiser. My themes have never changed. The only thing that ever changed in my work, and it had enormous influence in terms of commercial success, was the use of a first-person narrator who sometimes is a police officer. That’s what changed everything.

But nothing else changed. The characters, the settings, the themes, they’re all, for good or bad, out of the same source. Something that’s in the unconscious, I’ve never quite understood it."

On the appeal of Robicheaux: "Well, Dave Robicheaux is the everyman. He’s a very successful voice in the series because he’s someone whom the reader trusts. And the person who wrote first about establishing this kind of voice in narration was Washington Irving. We don’t talk about him much anymore, but Washington Irving – and Nathaniel Hawthorne – essentially invented the short story. Edgar Allan Poe is usually given credit; they were contemporaries.

Washington Irving said something I never forgot. He said the narrator must establish a familiarity and a sense of trust between himself and the reader. It’s a kind of an intimate relationship that doesn’t exist outside literature. I always remembered that quote from one of his journals. And years later, the guy who originated the Bonanza series, he was being interviewed and he was asked, 'How did you accomplish a series that ran for 15 years on Sunday night television?' And he said, 'We created a cast of characters whom the American family felt comfortable inviting into their living room.' It’s a great line."

On his characters’ persistence despite witnessing constant crime and corruption: "Cynicism is really the stuff of sophistry. It’s simplistic in nature, it requires no insight and it requires no creativity. Anyone can, in effect, be negative. This, ultimately, is the world we live in. We’re all nihilists. It’s an easier way of doing things, simply to see hopelessness in the world but to, in effect, allow one’s self to not be a part of the herculean effort it takes to do as well as one can and leave the world a better place.

I think it goes back to the Old Testament, the contract made between Yahweh and Noah. That’s a great story. And the rainbow was the archer’s bow that Yahweh hung in the sky and made a contract with creatures and people on board Noah’s Ark. These guys would try to make the world a better place. We forget that in the Old Testament that man lived in peace with the animals. The first creatures on the Ark are the animals. Man was meant to be a steward of the earth. That’s a pretty large responsibility. Take care of the earth. That’s the job."

Erik Spanberg is a regular contributor to the Monitor's Books section.