Elaine Pagels discusses the Apocalypse

Loading...

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, the Seven Seals, the Whore of Babylon: These stunning images alone would have turned the Book of Revelation into one of the most memorable chapters in the Bible.

But they're just part of an even more fantastic vision of a prophet thought to be John of Patmos. He introduces readers to a seven-eyed lamb, locusts with scorpion tails, horrific beasts, and a demonic number.

The author wouldn't have called himself a Christian. In fact, he violently disagreed with those who wished to pull his faith – Judaism – in new directions. Essentially, he was a fundamentalist fighting against the encroachment of fresh ideas that disturbed him deeply. But while he couldn't stop the evolution of his faith, his words lived on to intrigue and confound dozens of generations.

Are they the fever dream of a man with a remarkable imagination? Scenes of what he thought would happen in a matter of weeks or months? Or a vision of the far-away future, perhaps even of our own time?

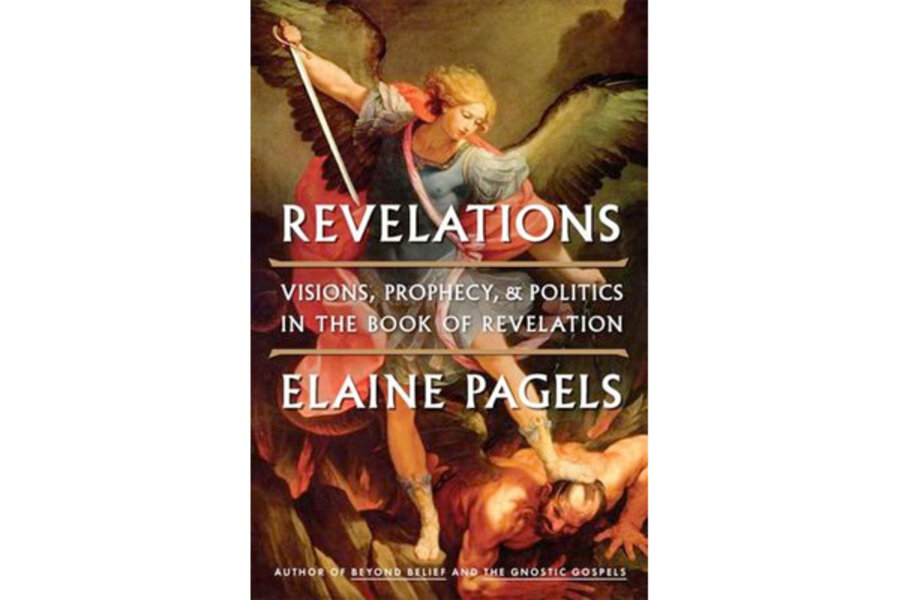

Elaine Pagels, a bestselling author and professor of religion at Princeton University, dives into the debate in her new book "Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation."

In an interview, Pagel talks about the eternal appeal of the Book of Revelation, the common ways that people misunderstand its meaning and its moving message about what we find in faith.

Q: The images of the Book of Revelation remain major touchstones in our culture. Why do you think that is?

A: It's very visceral. It doesn't appeal to the brain. It appeals to the bloodstream, as the Muslims say of the devil. It's a book of dragons, seven-headed beasts, monsters, whores, armies of insects fighting, angels and demons, and pits of fire.

Q: What was going on in the author's mind?

A: A lot of people say, "Is this guy on hallucinogenics or what?" But it's not an individual's fantasy. These are imaginatively transformed versions of ancient prophecies of Ezekiel, Daniel, Jeremiah, and Isaiah.

It's a book of prophecy. It's supposed to inspire people who have given up hope on any justice in the world. John wants people to hold onto that hope.

Q: He wrote the Book of Revelation at a time when there was intense debate over the future of the church and whether it was something different from Judaism. Where did John of Patmos fit in?

A: He's not somebody who'd call himself a Christian. He's somebody who's very proud of being a Jew – but one who knows who the messiah is – and sees himself in the line of the prophets.

He's a fierce, angry, conservative, passionate prophet. He's ferocious, with a kind of puritan sense of the importance of sexual purity and ethnic purity, compared to Paul, who's willing to eat unkosher food and eat with Gentiles and open up the movement to everybody. John doesn't think so.

Q: What do people misunderstand about the Book of Revelation?

A: A lot of liberal people think it's just crazy, and they can't understand how people have ever taken it seriously. They don't see that it is about war and politics, full of imaginative images of the political world of that era.

We'd have to think of ourselves as people whose families have been slaughtered to see how this author is seeing the forces of good and evil.

Q: Was he living in an era akin to our modern Holocaust?

A: The Romans weren't trying to kill all the Jews, but they did destroy Jewish resistance to Roman rule. Jerusalem was turned into a Roman army camp, and it was a total devastation.

Q: How long have people been interpreting the Book of Revelation as predicting events of their own lifetimes?

A: What's amazing to me is that for 2,000 years, people have been reading the signs of their own times into it: It was about the explosion of Vesuvius, it was about Nero. Because the images are so open-ended, it's been possible to reapply it again and again.

Q: You mention that both sides in the American Civil War turned to the Book of Revelation for support, as did those in World War II.

A: The Book of Revelation is such a dream landscape that you can plug any major conflict in it.

Q: What did you discover about "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," from the Civil War era?

"The lord is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored." It's full of battle imagery, and it's literally straight out of the prophecies of Jeremiah and the Book of Revelation. [In the King James version, Revelation 14:19 reads: "And the angel thrust in his sickle into the earth, and gathered the vine of the earth, and cast [it] into the great winepress of the wrath of God."]

Q: Tell me about the Antichrist. He doesn't actually appear in the Book of Revelation, but we think of him as being part of the apocalypse and the end times.

A: The Antichrist is often identified with the second beast in the Book of Revelation that arises from the land, the beast that tries to make everyone worship the power of evil.

Q: We do find the numbers 666 in the Book of Revelation, and they've been an eternal source of fascination. What do you think they stand for?

John is a Jewish prophet, and he hates Rome. Maybe he doesn't want to indict the Roman Empire publicly, even though he does that plenty.

He puts the number in the code called gematria, which equates a number with every letter: 666 is most plausibly read as the imperial name of Nero. He was understood by everybody to be the epitome to be the worst you could get as far as evil. People would have understood that.

Q: What is the ultimate value of understanding the Book of Revelation?

A: You can look at the 2,000 years of the way it's been read, in Europe and ancient Italy and from Augustine through the Middle Ages and beyond, and write the whole history of western Christendom by the way they're reading the Book of Revelation.

What's important to me is how it shows that the religious understandings of history and meaning are really not going away. They're very durable. They have to do with emotional responses to conflict, to ambiguity, to trauma like war and natural catastrophe.

The book says, okay, there is a lot of suffering and there's a lot of terrible things are happening, but they're all under God's control. It'll only last for a certain amount of time, and justice will prevail.

It shows religion is less about believing in a bunch of things than it is about having hope.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor correspondent.