How a murder changed China as it moved toward World War II

Loading...

In the 1930s, Peking is no Shanghai. It lacks the gloriously lawless panache that turned its fellow Chinese city into an international sensation.

Still, Peking has plenty of vice, much of it based right next to a diplomatic enclave full of Western-style hotels, saloons, and shops. It's a volatile mix, and in 1937 it becomes a deadly one: a vivacious young British woman is found brutally murdered and mutilated.

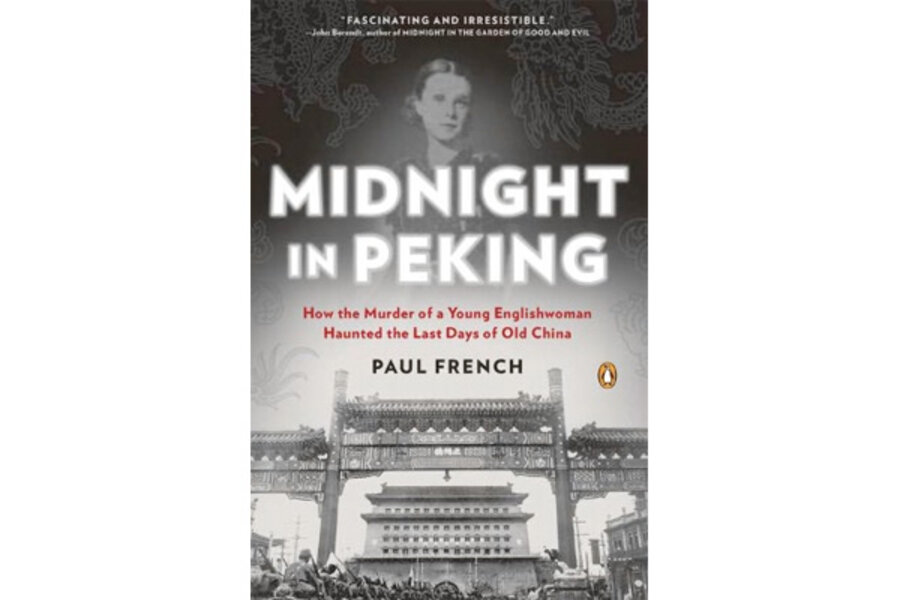

In his new book Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China, author Paul French tells the true-life story of a shocking murder that occurred as China itself stood on the edge of catastrophe in the shadow of a looming World War II.

"Midnight in Peking" is true-crime writing at its best, full of vivid characters, an exotic locale, secrets galore, and a truly bewildering mystery.

In an interview, French talks about the fear spawned by the death of a diplomat's daughter, the stray footnote that spawned his book, and the international "driftwood" who called China home during the Great Depression.

Q: What was happening in Peking – now Beijing – in early 1937, when the young woman was so viciously murdered?

A: This was absolutely the last gasp of old China. The Japanese have surrounded Peking, and it's not really a question of if Japan is going to invade China, but when.

Q: What did her murder mean in the larger picture?

A: In January 1937, she became a great symbol for foreigners and citizens alike in Peking about how bad things could get. If this could happen to a foreign privileged girl, what chances would anybody else have?

Later in 1937, the Japanese would invade and occupy Peking, bomb Shanghai, and commit the Rape of Nanking. That would leave the British Empire weak in facing the Japanese, and in a year Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaya would be gone to Japan. And we know what happened then.

Q: How did you come across this story?

A: I learned about it by reading a footnote in a very academic biography of the American journalist Edgar Snow, a Missourian who came out to China during the Depression.

He wrote the famous book "Red Star over China," and said this Mao guy may not be an idiot, and the Communists might be the ones who might take over. He over-glamorized Mao, but he's very well known for the book.

He and his wife lived in a traditional Chinese courtyard with a half-moon entrance gate and buildings on all three sides, on a very traditional street like the little lanes and alleys that made up Peking.

Their next-door neighbors were a British family called the Werners, a father and daughter.

He had been a very well-known diplomat in China and was retired and living as a scholar. His 19-year-old daughter was home for school for the holidays. On Jan. 7, she was murdered, and her body was found near a building called the Fox Tower.

Q: So you discovered the tale of an incredible murder by reading a footnote?

A: Only an academic would write a footnote more interesting than the text. They take fascinating subjects and render them bum-numbingly boring.

Q: What does your book tell us about that time and place?

A: It is a story of a small expatriate foreign community in a faraway place, in a different culture. There is a tendency for what we called white mischief – lots of scandals and lots of people losing their moral compasses.

There was a community, called the Badlands, made up of European and American lowlifes who went to China to become lost in a community that wasn't very policed.

Many were White Russians, those hundreds of thousands of Russians who left to escape the Russian revolution. Many ended up homeless and often penniless because they didn't have any skills. A lot went to China, where they tended to fall into the business of pimping, prostitution, and drug dealing.

Q: Peking had quite an underground world of crime and vice, didn't it?

A: Another place I write about quite a lot is Shanghai. When you mention Shanghai in the 1930s, a lot of light bulbs go off. Shanghai was jazz, gangs, and parties. It was like Chicago gone to the East.

People know about that one, Peking hasn't been written about as much.

Q: When it comes to vice and high-living, was Peking like Shanghai lite?

A: Yes.

When you’re in Shanghai, you’re in a treaty port, a kind of hybrid. By contrast, Peking is an ancient city and the former imperial city, and at this time it was a little bit of a lost backwater and wasn’t the capital of China.

It was a city of 3 million people with about 3,000 foreigners that had been the capital and center of China.

The foreign embassies had secured a square mile in the center of Peking. The buildings are still there: in this very Chinese city is a square mile of buildings that look like Bloomsbury of London.

This was where respectable foreign Peking lived, with department stores and bakeries and respectable Western apartments. Just next door was this area of sin and vice run by the White Russians and various driftwood from Europe and America.

They called them "the driftwood," which I thought was very good.

What Pamela's murder showed was the overlap between the responsible people and the Badlands.

Q: Is there any hero in this story?

A: The hero is the father [who was a major suspect]. I think that he solved the crime.

In the book, he comes across to Americans as a cold, unemotional father. He's so unemotional that people say he’s almost autistic.

He’s not autistic, he's English.

To me he was just an English father. That’s what our dads are like: We're sent away to school at a young age. I shake hands when I see my father, I don’t hug him or anything like that.

Q: What are you working on next?

A: I live in Shanghai, and I want to do the great book about the gangs and the girls, the jazz and the dope, and the guns.

It was the Wild East, Chicago writ large: Big Trouble in Big China.

Shanghai was crazy in those days, and the place to be in for a good portion of the world's completely bad folks. It was wild.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.