Right pricing e-books: Is the government actually discouraging competition?

Loading...

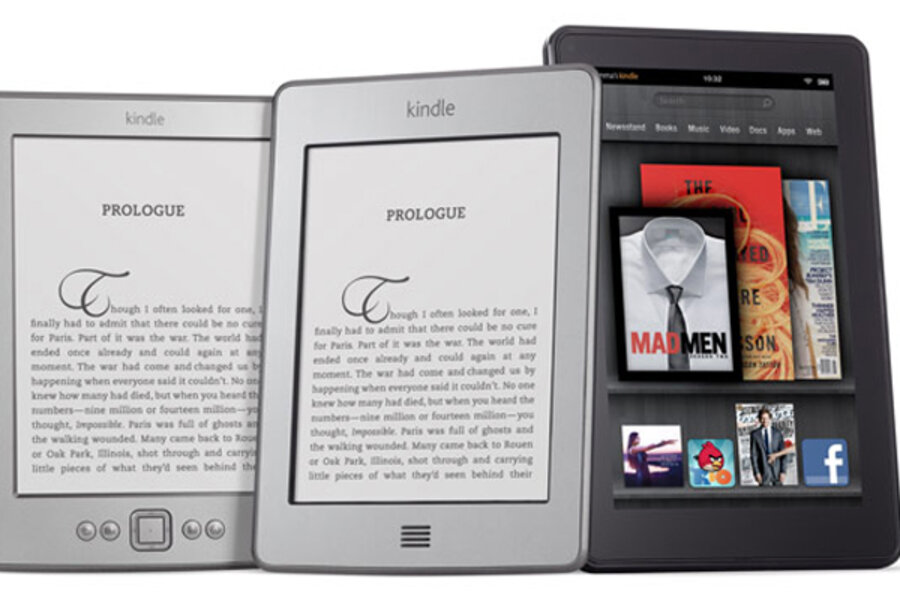

Might Apple’s agency model – in the crosshairs of a Justice Department investigation over price fixing – actually encourage competition rather than kill it?

That’s the latest question circulating publishing forums and tech blogs since last Thursday’s news that the Justice Department may be close to filing an antitrust lawsuit against Apple and five publishers. What’s more, interested parties like the Authors Guild, a writers’ advocate group, are coming forward to defend Apple’s agency model.

“The irony bites hard,” writes Authors Guild President Scott Turow in an open letter defending the agency model. “Our government may be on the verge of killing real competition in order to save the appearance of competition.”

Let’s back up. The DOJ is threatening to file a lawsuit against five publishers (Hachette Book Group, Simon & Schuster, MacMillan, Penguin, and Harper Collins) and one distributer (Apple), all operating under the agency model and all suspected of e-book price collusion.

There are two competing models for distributing books, print or electronic: the wholesale model and the agency model. Under the wholesale model, a publisher sells its goods to a distributor for a fixed price and the distributor is free to decide the actual price for the public (including selling at negative margins to dump books on the marketplace in the case of Amazon). Under the agency model, publishers set the retail price and the distributor gets a fee (30 percent in the case of Apple).

The problem, writes Turow of the Authors Guild, is that wholesale pricing gives distributors control at the expense of the publishing industry. “Amazon was using e-book discounting to destroy bookselling, making it uneconomic for physical bookstores to keep their doors open,” he writes.

That’s because the primary purpose of the wholesale model is to serve the retailer’s (in this case, Amazon) interests, even if it means throwing publishers under the proverbial bus. (For example, it is in Amazon’s interest to price-dump top-selling e-books at a loss in order to promote sales of other products or up-sell high-margin items through its recommendation engine, writes Guardian tech reporter Frederic Filloux.) What’s more, the wholesale model is deflationary, encouraging retailers to push margins ever lower to attract and capture customers. That threatens physical books, and with it, bricks-and-mortar bookstores, writes Turow of the Authors Guild.

He explains Amazon’s pricing scheme in detail:

“Just before Amazon introduced the Kindle, it convinced major publishers to break old practices and release books in digital form at the same time they released them as hardcovers. Then Amazon dropped its bombshell: as it announced the launch of the Kindle, publishers learned that Amazon would be selling countless frontlist e-books at a loss. This was a game-changer, and not in a good way. Amazon’s predatory pricing would shield it from e-book competitors that lacked Amazon’s deep pockets. Critically, it also undermined the hardcover market that brick-and-mortar stores depend on. It was as if Netflix announced that it would stream new movies the same weekend they opened in theaters. Publishers, though reportedly furious, largely acquiesced. Amazon, after all, already controlled some 75% of the online physical book market.”

It’s no wonder, he writes, that when Apple entered the market with its iPad and Apple’s newly-pioneered Agency plan, publishers “leapt at Apple’s offer and clung to it like a life raft.… [I]t was seize the agency model or watch Amazon’s discounting destroy their physical distribution chain.”

It’s unclear whether or not the publishing industry colluded in entering the agency model, but it appears it did move in accordance with its best interests. And, if we are to believe Turow’s argument, with the best interests of readers and bricks-and-mortar bookstores.

Whether the DOJ reconsiders its lawsuit or continues to pursue Apple and its agency model remains to be seen.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.