Before 'O': a 19th-century anonymous sensation

Loading...

Will the unnamed author of "O," the new novel about a quasi-realistic 2012 presidential campaign, take his or her identity to the grave? Considering the horrific critical reaction to the book – "trite, implausible and decidedly unfunny," grumbled Michiko Kakutani in the New York Times – it might not be a bad idea. And there just so happens to be some precedent.

The anonymous author of a sensational and female-friendly 19th-century bestseller about the dangers of a socialist revolution never fessed up. But the unknown writer of "O" might not want to follow this precedent too closely: Everybody eventually figured out who wrote 1883's "The Bread-winners," which would one day hold the dubious distinction being "the first important polemic in American fiction in defense of Property."

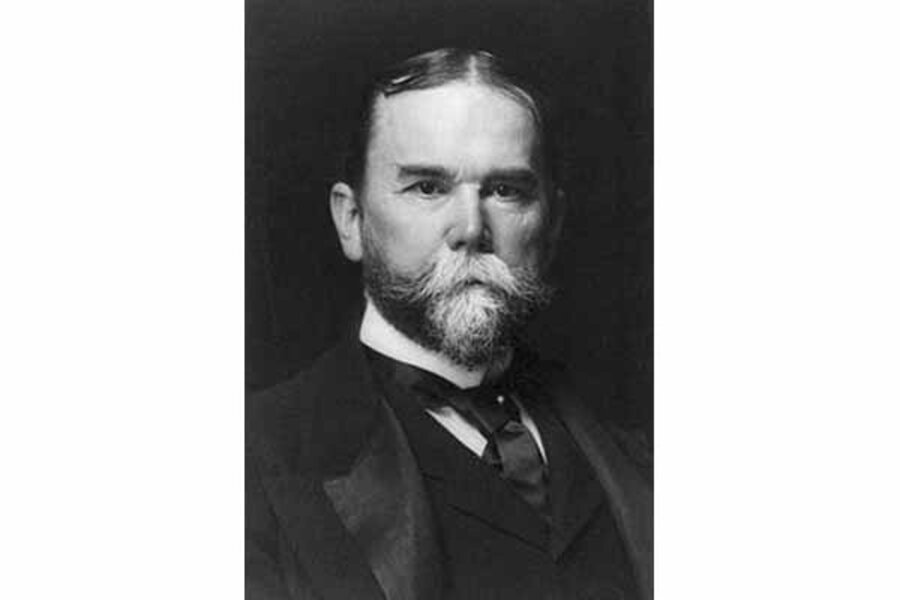

The anonymous author was John Hay, a private secretary-turned-diplomat who managed to serve not one but two assassinated presidents in a life that also included a stint in journalism, an ambassadorship and, it seems, a lot of time spent learning to understand the ladies.

5 must-read books coming out in early 2011

Hay first made a name for himself as a young man by serving as Abraham Lincoln's secretary in the White House. Amid the violent tumult of the 1870s, he busied himself by tut-tutting about "how the very devil seems to have entered the lower classes of working men, and there are plenty of scoundrels to encourage them to all lengths."

Socialism, he thought, was a scourge. A threat to democracy too. And, of course, a worthy topic of a novel. And so "The Bread-winners" was born.

The novel isn't just a tale of the battle over the future of civilization. It has a love story too. But, as a Hays biographer writes, "you become almost too absorbed in the struggle between Labor and Capital to care whether Farnham and Alice marry or not."

That's quite some literary trick, even today.

The biographer says "The Bread-winners" was the most successful in American history up until its time. It became a smash international success, was translated into French and German, and inspired massive speculation about the identity of its author. (Sound familiar?)

"The literary journals devoted columns to correspondents, some of whom proved that the author must be a man, while others insisted that only a woman could understand the heart of Woman as the unknown writer had done," the biographer reports. "The name of nearly every literary worker was suggested."

One New York City reader even suggested to Hay that he let her take credit for the book since he obviously didn't want it. "If you are willing to resign all rights and title to it, I shall be most proud to give it a permanent home and standing."

Moxie!

So does "The Bread-winners" still hold up today? Your humble correspondent can't say for sure, since he was quite exhausted by the first two sentences: "A French clock on the mantel-piece, framed of brass and crystal, which betrayed its inner structure as the transparent sides of some insects betray their vital processes, struck ten with the mellow and lingering clangor of a distant cathedral bell. A gentleman, who was seated in front of the fire reading a newspaper, looked up at the clock to see what hour it was, to save himself the trouble of counting the slow, musical strokes."

Whew.

Hay would go on to become secretary of state for William McKinley and, briefly, Theodore Roosevelt. He died in 1905, and his book vanished into forgotten history, along with his not-so-secret authorship and his apparently unparalleled insight into the "heart of Woman."

Randy Dotinga regular blogs for the Monitor's book section.