Oh, rats! This rodent book is a treat

Loading...

Here's a recipe for you: Take some Vienna sausage, sardines, and Kit Kat bars. Then slather them with peanut butter. It sounds like a delicacy fit only for an alley rat in New York City.

So when an intrepid author-turned-rodent researcher set down his concoction in a rat-infested alley in Manhattan, you might assume rats would drop by for a bite and get snared by the attached trap. But they didn't, not a single one.

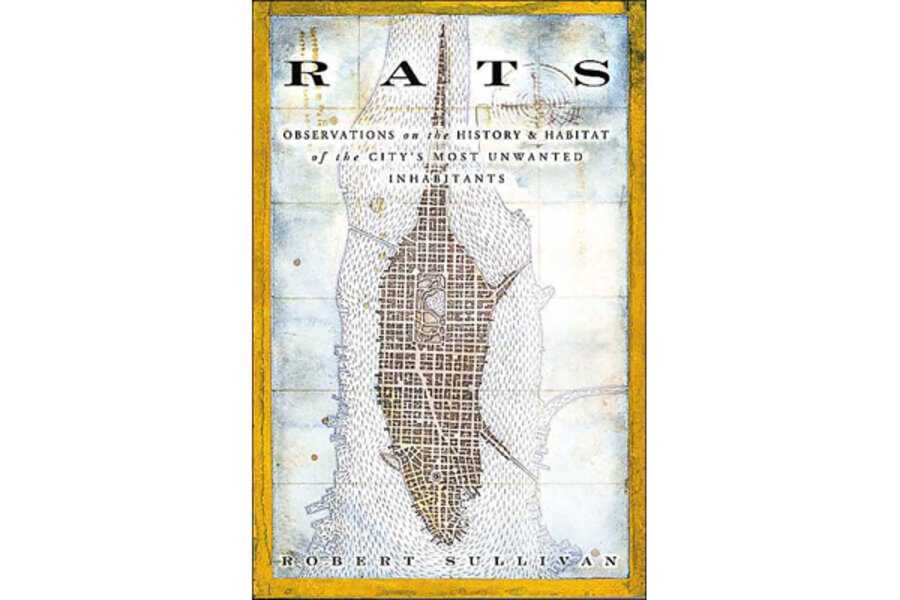

It turns out that rats are "incredibly skittish, wise-seeming, even," writes environmental journalist Robert Sullivan in his 2004 book, "Rats: Observations on the History and Habitat of the City's Most Unwanted Inhabitants."

Rats don't like new or different things, and that's one of the reasons why they still surround us despite hundreds of years of efforts to make them go away. Instead of wooing rats into their clutches, traps make them nervous.

Take-home message: Those rats are pretty smart.

That's just one of many facts that now make up my storehouse of rat knowledge thanks to Sullivan's book, which I stumbled upon a couple weeks ago. Its wry blend of biological and cultural history has held me in its grip ever since.

It helps that I like to read about dark things, and rats certainly have a well-deserved reputation as being among the most despised animals on earth. They feast on the leftovers of human society, they bite, and they spread filth. Worst of all, there's a good chance that a whole bunch of them are near you this very instant, even in the fanciest homes and hotels.

The intrepid Sullivan spent months watching rats in action, observing "a nighttime symphony of movement, a chorus of disgustingness." (And here you thought journalists just sit in front of computer screens all day growing pale. Present company excluded, that's not always the case.)

Sullivan tracks the history of rats and humans back for centuries, finding examples of times when rats played roles in dramas on the political and medical fronts. He also finds plenty of eccentric characters who devoted their lives to studying rats or figuring out ways to send them to that great garbage heap in the sky. And perhaps best of all, he looks at the Big Apple's past through an unexpected and unique prism: the rise of rodents.

So how do you make rats go away? Rats tend to be too wily to fall for mousetraps. And contrary to popular belief, felines won't mess with the nasty critters. (If you do put Fluffy in the basement to do battle with rats, don't be surprised to find her skeleton in a day or two. Seriously.)

Exterminators have their ways with poisons, of course, but even they're often flummoxed by clever rodents. Even a single stubborn rat can keep exterminators occupied for days.

So what to do? Cleanliness, it turns out, is next to rat-less-ness: Rats go away without food to eat and water to drink. To keep the killing of rats down, there's talk of designing buildings that are less hospitable to infestation.

But as long as there are dark alleys full of food-filled garbage cans, there will be rats. Lots of rats that aren't likely to ever again see a platter of sausage, sardines, and chocolate with a peanut butter chaser.

Actually, that doesn't sound too horrible. Maybe I'll just have a bite and ignore that metal thing with the … OUCH!

Randy Dotinga is a frequent Monitor contributor.