"Poisoning the Press": The story of a real-life plot by the Nixon White House

Loading...

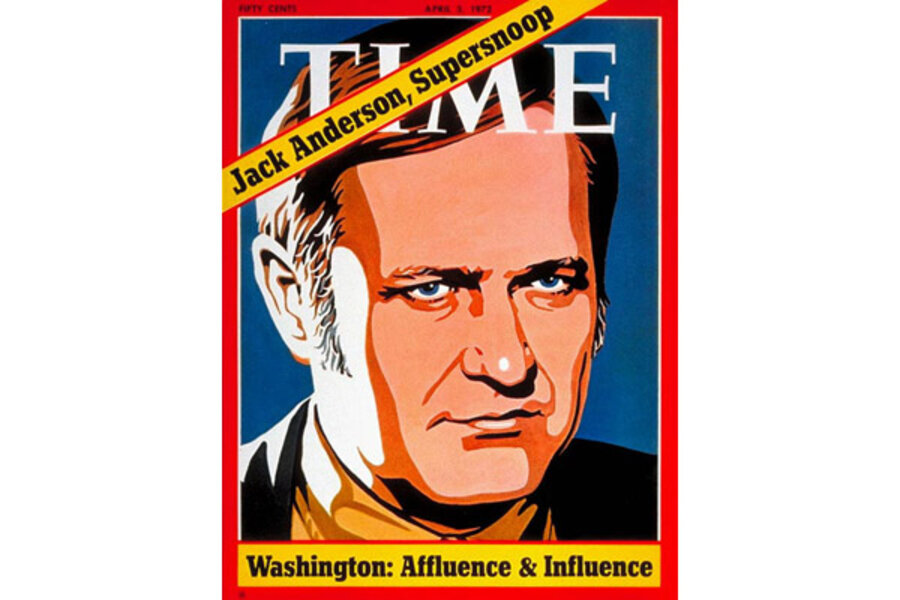

Syndicated columnist Jack Anderson had the White House on the run.

With just months until the 1972 election, he'd exposed a blatant bribe within the Nixon administration. Now, the president's men had him in their sights more than ever before. They discussed poisoning his aspirin or sending him into a dangerous hallucination by smearing LSD on his steering wheel.

This was no joke. In his new book, Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington's Scandal Culture, journalist and University of Maryland professor Mark Feldstein chronicles the real-life assassination plot that topped off an epic feud between the columnist and President Richard Nixon. Both men, he writes, lost their bearings in a world of lies, blackmail, and corruption.

I talked to Feldstein, who once worked for Anderson as an intern, about what he discovered while researching "Poisoning the Press."

Q: You write that Richard Nixon was paranoid about the press and had every right to be because it really was out to get him. Which came first, his paranoia or the reason for it?

The paranoia came first. There were people in college who talked about him being paranoid long before the press started attacking him, even before [columnist] Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson started going after him in the early 1950s. He would completely overreact to the very mild criticism at the time he was sending [accused spy] Alger Hiss to prison when he was a congressman.

He was lionized by almost the entire media except for a handful of dissident liberal critics, but he was so sensitive and paranoid that he really overreacted.

He viewed himself as a victim and never seemed to realize that he made himself a target by his own initiating of these slash-and-burn attacks on supposed Communist subversion. By the time he became a national figure, there were critics on the left going after him. Certainly Jack Anderson and his boss, Drew Pearson, were out to get him.

Q: Why did they hate him so much?

Drew Pearson was a liberal, very ideological and, like Nixon, was a Quaker. But he was a pacifist compared to the fundamentalist, almost evangelical strain of Quakerism that Nixon was raised in. He was very much of what we'd call a born-again Christian today.

With Anderson, it wasn't so much ideological. He was willing to attack people on the right or the left, but he thought Nixon was a crook, and he was right.

Q. Do you think Anderson realized that he was unhinging the presidential administration so much that he was actually in danger of being killed?

He had no concept. He knew he was being followed, but he didn't know the extremes of how the White House was going to stop him.

Q: The assassination plot by Nixon's operatives was really serious?

It was much more serious than anyone has realized to date. In my research, I found evidence showing that Washington prosecutors investigated this seriously.

This plot went beyond the talking stage. They acted on it by meeting with a CIA poison expert about how to poison him in a way that wouldn't be detected in an autopsy. This definitely got further along than anyone knew, and it got called off at the last minute because there was a more important target – to break into the Watergate complex.

Q: You write that Anderson engaged in plenty of ethically dubious activities himself as he tried to uncover corruption in Washington D.C., Could he have uncovered what he did if he'd been completely ethical?

No, I don't think so. I think that's how he justified it to himself.

Power is almost inherently corrupting: it's the ability to get people to do things they don't want to do. You do that with carrots and sticks. Some of his carrots included reflecting a source's point of view and, in a handful of cases, the carrots included money. And the sticks in some instances included blackmail.

These tools did work. Part of why Anderson is so important is he got information that no one else had. A case can be made that in the long run, it was to the public's benefit that he engaged in bribery and blackmail, as unethical as they were.

It's a very slippery slope, telling lies to expose the truth. But the fact of the matter is it worked.

Q: What is the big lesson of what you found for today's world?

For all of his faults, Anderson was a really important although neglected figure in American journalism who exposed wrongdoing when the rest of the Washington press corps was supine. He held the lonely banner of muckraking aloft in the middle of the 20th century and helped keep it alive during that dry spell from the original muckrakers of a century ago until a new generation could take over in the Watergate era.

In terms of a larger lesson, it's simple but important: power corrupts. Whether you're a politician or a journalist, it corrupts in similar ways.

Both Nixon and Anderson came to Washington as idealists and had a rude awakening in how devious and cynical the nation's politics and press can be. They both thought they were going to campaign against this corruption, and both ended up succumbing to it.

Randy Dotinga regularly reviews books for the Monitor.