‘Daughter of Daring’ tells a rip-roaring story of Hollywood’s first stuntwoman

Loading...

In the earliest days of film, one star was such a box-office success that she was able to sustain a career in Hollywood over 45 years and hundreds of movies. But despite Helen Gibson’s loyal fans, her fearless stunts, and her role as a pioneer, not many people know about her today.

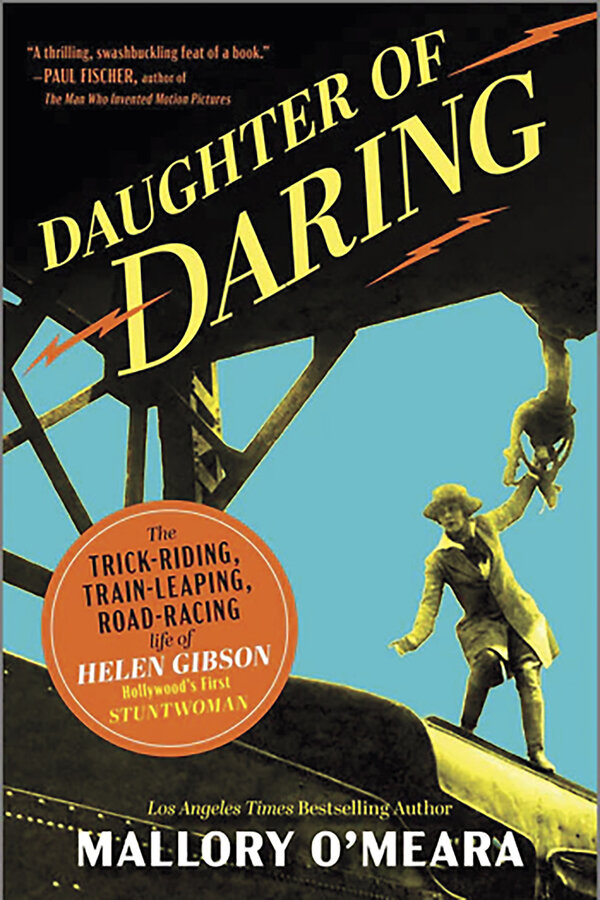

Mallory O’Meara’s biography “Daughter of Daring: The Trick-Riding, Train-Leaping, Road-Racing Life of Helen Gibson, Hollywood’s First Stuntwoman” dusts off Gibson’s remarkable legacy.

As the book demonstrates, Gibson became a beloved icon because she offered female viewers a kind of wish fulfillment. Her emergence on screen coincided with a post-World War I era in which many American women felt like they were being told, in essence, “Thank you for serving in the workforce while your brothers and husbands were away fighting, but now that the war is over we want men to take the reins again.” Women were encouraged to go home, keep house, and have babies.

And go to the movies.

Initially, theater houses exhibited short clips in dingy rooms and were considered little more than two-bit sideshows. To evolve into more lucrative, quality entertainment, theater owners collectively decided to revamp their spaces and market specifically to female audiences.

The new clientele was immediately struck by Gibson. In serials like “The Hazards of Helen” and “A Daughter of Daring,” the “girl who tames trains” – as she was dubbed – was strong and full of agency. She was in command of situations in a way that real-life women often were not. On camera, Gibson could fight fist-to-fist with male villains and wrangle out of any bind.

Perhaps Gibson could relate to her fans. Having grown up in the 1890s in Ohio near Lake Erie, Gibson spent her childhood outdoors, swimming and climbing trees. But as she got older, she found that her hometown was a place of convention, of quiet submission for women, which meant working long hours in the local cigar factory for little pay. When a newspaper ad told of a Wild West show looking for horseback riders – women included – she jumped at the opportunity.

Fortunately for Gibson, she was a natural.

She could swing down from a saddle to pick up a handkerchief on the ground within her first few weeks of training. Looking back on the experience, Gibson told a film magazine, “When veteran riders told me I could get kicked in the head, I paid no heed. Such things might happen to others, but could never happen to me, I believed.” As she was a top-notch performer on the rodeo circuit, it was only a matter of time before she landed in Los Angeles.

The author is also quick to note that even by today’s standards, Gibson’s is a name worth remembering. On modern sets, for example, stunt coordinators choreograph every move. But in Gibson’s day, the only person looking out for her safety was Gibson herself. No one would insure her. What’s more, because she was working during such an early period in film, she did everything without protective gear.

For those interested in watching Gibson’s work, they can still see her in episodes of “The Hazards of Helen” such as “The Wrong Train Order.” Although many of her reels from the silent film era have been lost to time, O’Meara’s book ensures that the memory of the “queen of the rails” is here to stay.