Forgotten Muslim builders gave medieval Europe its iconic architecture

Loading...

Notre Dame Cathedral. Westminster Abbey. Lisbon Cathedral. The Leaning Tower of Pisa.

All are architectural wonders and illustrious examples of the Romanesque style of architecture, which blossomed in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries. While all these buildings have very strong national identities and associations, their design and construction – executed at the highest level of artistry in the world – were not of European origin, but were derived almost entirely from the Muslim world.

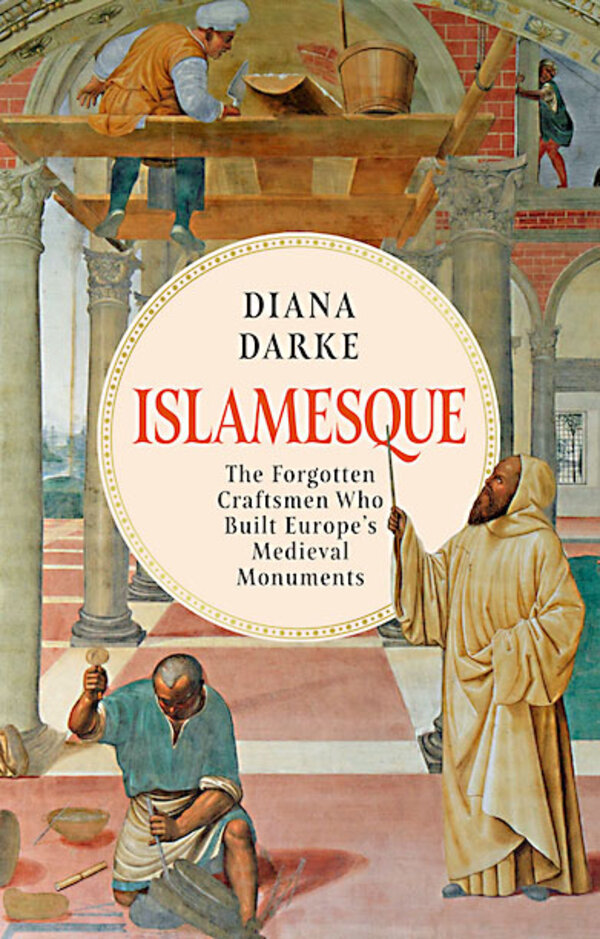

In “Islamesque: The Forgotten Craftsmen Who Built Europe’s Medieval Monuments,” historian Diana Darke offers up a pioneering work of scholarship that strives to give credit to the innumerable Muslim artisans who produced these architectural marvels. So great is the Romanesque’s debt to them, Darke argues in an audacious challenge to art historical orthodoxy, that the style should more properly be called “Islamesque.”

“Romanesque” is the name art historians have given to the architectural style that emerged across Italy, France, England, and Germany, making it the first pan-European architectural style since Imperial Roman architecture. The name was meant to invoke the rebirth of classical Roman values, which brought the Dark Ages to a close and ushered in the Renaissance.

Darke notes that architectural styles usually change very gradually, evolving over many generations. “No new style just pops out of nowhere,” she writes. “It always grows organically out of an earlier one, building on what came before.”

So where did the Romanesque style come from? How did it spring up and across such a wide swath of Europe when it did? What occurred in the 11th and 12th centuries that could account for such a phenomenon?

The answer, in her view, is that a highly skilled workforce – Muslim architects and artisans – entered Europe over those two centuries and brought with them a wide array of advanced techniques in construction and decorative crafts derived from their own cultural heritage.

The Muslim world was about two centuries ahead of Europe, which was quite backward at the time. People in Europe were almost entirely illiterate, while there was a high degree of literacy and numeracy in the Muslim world. Muslim architects, engineers, and artisans led the world in their understanding of geometry, optics, woodworking, mining, metalwork, stone carving, and other fields. The Golden Age in Andalusia and Sicily saw a widespread intermingling of Arabs, Christians, and Jews. “It was from the seeds of this crucial 200-year cross-fertilisation that the style we now call ‘Romanesque’ was born.”

Darke begins her study with Egypt’s Fatimid dynasty, which founded Cairo, and moves through North Africa and the Andalusia region of southern Spain, where Arab Muslims from Syria ruled for some 800 years. She makes close examinations of mosques, churches, minarets, and other structures across North Africa, the Mediterranean, and Western Europe, and finds innumerable elements of Muslim architecture later replicated in Romanesque structures.

Darke is an Arabist who has written extensively on Middle Eastern culture, and her foray into this particular study was sparked by a cryptic zigzag pattern decorating a wall of her own courtyard house in Damascus. Her study led her to similar patterns rendered on Norman (another term for Romanesque) churches in France and England.

Indeed, she notes that “The particular features associated with the Norman style across Britain and Ireland, from the advanced vaulting to the distinctive styles of ornamentation, all derive without exception from the Islamic world, brought in by the Normans influenced by the Arabic styles they learnt in Sicily, in the Italian mainland and in Muslim Spain.”

As Muslim dynasties in Europe began to crumble by the end of the 11th century, Muslim craftsmen remained in Europe and went to work for new employers. Wealthy Christians were building churches, cathedrals, and the like – some of the highest profile projects of their day – and wanted the best workers available.

In addition to giving credit where credit is due, Darke makes a larger point in “Islamesque” about the interconnectedness of global culture. “In today’s world of shrinking horizons and narrow nationalisms,” she writes, “it is more important than ever to understand how closely interwoven the world’s cultures are and how much we owe to each other, even though we may be from different races and religions.”

While the author herself is not an academic and the book is written for the nonspecialist, “Islamesque” will have the greatest appeal to readers with a strong interest in architecture or European history. The book includes a helpful glossary of historical and architectural terms. Scores of excellent color plates depict most of the magnificent structures under discussion and illustrate many important architectural details.